Introduction

In Soweto1 on 16 June 1976 thousands of black students demonstrated against the introduction of ‘Afrikaans’2 in education. They shouted: ‘Down with Afrikaans, the language of the oppressor’ and their slogan was ‘Viva Azania’.3 Ruthlessly the army and police massacred the peacefully demonstrating students. These dramatic events had a major impact on the course of the liberation struggle and international solidarity.(part I)

Western Anti-Apartheid organizations determined to a large extent with their activities which black resistance organization in South Africa should be

supported. They successfully pleaded with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), churches and governments their case for exclusive political and materialsupport for the ANC (African National Congress). If necessary historical facts about the Soweto uprising and other acts of resistance were manipulated in favour of the ANC. The liberation movements PAC (Pan Africanist Congress) and BCM (Black Consciousness Movement) organizations were discredited in a variety of ways and paid for this a heavy price in and outside South Africa.(part II)

Since 1994 the ANC has ruled in South Africa. From their dominant position the ANC follows the pattern of inappropriately claiming people and acts of resistance during the liberation struggle. In school textbooks and museums the ANC version of history is central.(part III)

I

Soweto 1976

Prologue

‘Afrikaans’ and Bantu Education

The Apartheid regime strove to realize the ideal of ‘Afrikaans’ as the only official language in South Africa. Together with Bantu education for the black population it turned into an instrument of political control. Bantu education trained black people to manual and unskilled labour. At the same time black people were made to accept they were subordinate to the white minority. This policy was legitimized by the Bantu Education Act in 1953. The Act fitted in with the policy of Apartheid that stood for discrimination and segregation based on skin colour.

Protests against this racist educational policy date back to before the Act was passed. The Transvaal African Teachers’ Association (TATA) led by Zeph Mothopeng4 decided to reject the Bantu Education Act. In 1952 the members stated in a resolution to commit themselves to the complete destruction of Bantu education and to free and universal education for Africans.

Black Consciousness Movement

The Black Consciousness Movement originated from the launch in 1969 of the black student organization SASO (South African Students’ Organization). In a resolution SASO rejected the entire Bantu educational system. This was the starting point for the 1976 students’ uprising.

Medical student Steve Biko became the first president of SASO. The founders of SASO were dissatisfied with the policy of NUSAS (National Union of South African Students), dominated by white liberal students. Despite the pressure from black members NUSAS barely addressed the problems they had to deal with in Apartheid South Africa. Problems that went far beyond the university campus. White students in their shielded districts hardly realized ( and actually did not want to know) what the Apartheid regime meant on a daily basis in all aspects of the lives of black people.

Biko wrote that it is fundamental to acknowledge that complete identification by white people with an oppressed group is inconceivable in a system that forces one group to have privileges and to live using the labour of the other group. He pointed out: ‘The biggest mistake the black world ever made was to assume that whoever opposed apartheid was an ally’.5

In 1970 SASO did not accept NUSAS any longer as the representative body of all students in South Africa. SASO rejected the negative term ‘non-white’ in relation to ‘white’. SASO members were Africans, ‘coloureds’ and ‘Indians’.6 According to SASO they were all black in the political sense of the word. They belonged to the oppressed majority in South Africa.

With the slogan ‘Black man you are on your own’ SASO focused on the organization of the black population. It echoed Sobukwe’s quote: ‘To go it alone’ at the formation of the PAC in 1959. It stemmed from the same criticism on the restraining and dominant influence of white liberals in determining the tactics and strategy of the ANC.

In 1972 the Black People’s Convention (BPC) was launched, an umbrella organization of socio-political organizations inspired by the ideology of the Black Consciousness Movement. Winnie Kgware was elected as the first president. As the first woman in South Africa she led a political organization.

The BPC and its organizations operated outside the Apartheid institutions such as the Bantustans7 or, for example, the Coloured People Representative Council, formed by the regime. For example, the Black Community Programmes organized, among other things, medical clinics, publishing companies, theatre companies and the black theology of liberation was developed.

A special relief organization, Zimele Trust, was formed for the many political prisoners and their families. After the Sharpeville Massacre8 and the ban on the ANC and PAC these organizations went underground and started the armed struggle. The Apartheid regime took extreme violent action. In the years between 1962 and 1967 mainly POQO 9 (PAC armed wing) freedom fighters were killed during hostilities, imprisoned, tortured, sentenced to death and hanged.10 The families of these people stayed behind, even further impoverished.

BPC and SASO put the mobilization of black workers first. The black union BAWU (Black Allied Workers Union) was set up. Foreign investors were called upon to withdraw from South Africa. With this demand the BPC wrote to more than thirty foreign companies.11

Strikes

In the course of 1972 there were strikes in several places. In Cape Town and Durban dockworkers were on strike for higher wages. In Johannesburg bus drivers were on strike. In 1973 there was a wave of strikes in and around Durban. The striking workers worked in a wide range of industries such as sugar, rubber, chemistry, bakeries, construction, carpets, fruit, meat and textiles.

At the multinational Anglo American Cooperation in Carletonville (one of the regions in the world producing most gold) near Johannesburg in 1973 black miners were on strike against the significant pay gap between white and black miners. The Anglo American Cooperation, claiming to be against Apartheid, sent the police to the strikers. Eleven miners were killed.12

During the strikes in these years a considerable degree of solidarity developed between Africans and people of Indian descent despite Apartheid policy. It strengthened the black unity the BPC organizations were fighting for. The Apartheid regime feared subversion against the State by the increasing influence of the Black Consciousness Movement on students and workers throughout the country. Standard repression was increased as a precaution.

Assassination SASO leader Tiro

In February 1973 8 Black Consciousness Movement leaders were issued with a ‘banning order’: Steve Biko, Barney Pityana, Drake Koka, Saths Cooper, Ranwedzi Nengwekhulu, Strini Moodley, Jerry Modisane and Bokwe Mafuna. Minister of Justice Pelser accused them of promoting ‘arson, rape and a bloody revolution’. They were not brought to trial because the regime wanted to prevent them from using the courtroom as a political platform.13 The ‘banning order’ meant limits to the exercise of the freedom of movement and communication with others. More ‘banning orders’ and house arrests were to follow. Mosibudi Mangena 14, then national BPC organizer, was sentenced to 5 years on Robben Island under the Terrorism Act.

In spite of the arrests and ‘bannings’ the BPC managed to organize well-attended rallies in March 1973 to commemorate the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 and the uprising afterwards.15

Onkgopotse Ramothibi Abram Tiro, an influential SASO leader, was expelled from the university in 1972 after a critical speech on the applicable 1953 Bantu Education Act.16 this he taught history at the Morris Isaacson High School in Soweto in 1973. In his history classes the SASO leader taught his students to ask critical questions about the content of history textbooks made mandatory by the Ministry of Bantu Education.

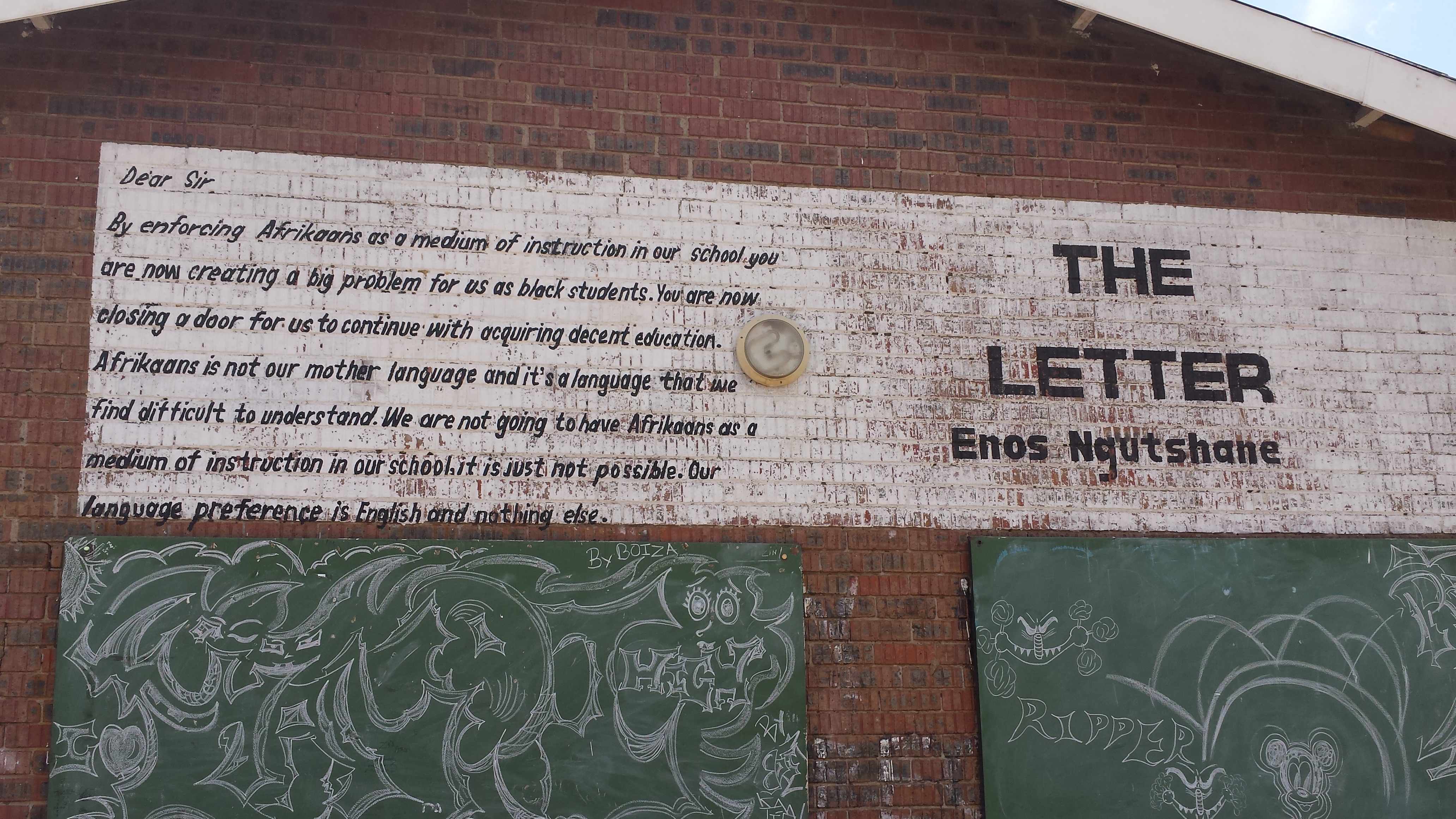

Tiro’s action was also an inspirational element in forming the student union SASM (South African Students Movement) based on the ideology of the Black Consciousness Movement. Tsietsi Mashinini, in 1976 a leader of the Soweto student revolt, was one of Tiro’s students.

After 6 months the regime forced the school to dismiss Tiro. The police prepared his arrest. By the end of 1973 he was forced to leave the country.17He could not escape the murderous regime. Early 1974 the regime assassinated Tiro (26 years old) in Gabarone, Botswana, with a letter bomb.18

Viva FRELIMO

On 25 September 1974 BPC and SASO planned solidarity rallies with FRELIMO, the Mozambican liberation movement. The former Portuguese colony was on the eve of its official independence. The rallies in among others Durban, Cape Town, Port Elisabeth and Johannesburg were banned by the regime.

Nevertheless, thousands of people gathered in the Curries Fountain stadium in Durban. They shouted ‘Viva Frelimo’, sang revolutionary battle-songs and performed the Black Power salute. After thirty minutes the police attacked and arrested many people. Even in hospitals people were arrested. They were there to be treated for serious injuries by police dogs.

That evening leaders of SASO, BPC and BAWU were arrested throughout the country. Many of them fled or went underground. Strikes and bus boycotts (against the high fares)19 continued. Many were killed by police violence.

In 1975 the BPC took the decision to fight for a free Azania (the new name for South Africa) on the basis of free elections that would result in a majority government.

SASO/BPC trial

Shortly after the pro-FRELIMO rallies 9 SASO and BPC leaders were arrested. A lengthy trial followed in 1975 and 1976. The 9 accused: Saths Cooper, Muntu Myeza, Mosioua ‘Terror’ Lekota, Nchaupe Aubrey Mokoape, Pandelani Nefolovhodwe, Nkwenkwe Nkomo, Kaborone ‘KK’ Sedibe, Zithulele Cindi and Strini Moodley. They were accused of conspiratorial activities during the period of 1968 -1974. The activities were allegedly aimed at altering the State by force and at slighting white people by representing them as inhumane oppressors of black people. Evidence were the, according to the prosecutor, subversive and anti-white texts in writing, poetry, plays, organizing anti-white rallies and the appeal to foreign companies to no longer invest in South Africa. A number of the accused remained in solitary confinement for 70 days.20

On 21 December 1976 the court found the 9 guilty under the Terrorism Act and sentenced them to five and six years of imprisonment. The next day they were taken straight away from Pretoria to Robben Island to serve their sentence.

One of the nine, Nchaupe Aubrey Mokoape, had already been detained in 1960 as a 15-year-old PAC member. At that time he was sentenced to three years of imprisonment for co-organizing demonstrations against the Pass laws, ending in the Sharpeville Massacre.

The trial received a lot of publicity because of Steve Biko’s testimony for days in defense of the 9 accused. Biko used the court as a platform to clarify SASO’s and BPC’s policy.21 His testimony was elaborately covered by the press. It was a hot topic.

Accused Pandelani Nefolovhodwe testified that the Bantustan/homelands policy 22 was considered a scam by the black population. During the trial the accused sang revolutionary songs and performed the Black Power salute.

Preceding events

To commemorate the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 thousands of people gathered in Soweto in March 1976. The trial against the SASO/BPC leaders was in progress and the trial against 7 leaders of the NAYO (National Youth Organization) started in March. The accused, inspired by the SASO/BPC trial, stood trial with their fists raised.

Outside the courtroom the Black Consciousness Movement organizations organized solidarity demonstrations. The police responded violently. In May two of the accused were sentenced to five years of imprisonment for recruiting people for military training.

In the same month 25,000 residents of the township Kwa Tema started a bus boycott against the price increase of the fares.

Uprising 16 June 1976

The compulsory introduction of ‘Afrikaans’ at secondary schools provoked anger in parents, teachers and students. Abruptly students had to study and take exams in a language they hardly commanded. In addition, ‘Afrikaans’ was hated because it was the language of the oppressor. The police, the judicial system and the Apartheid regime used this language.

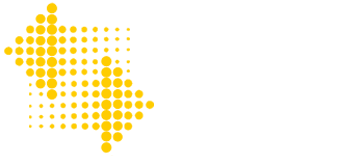

The student Enos Ngutshane, local SASM leader, wrote in April a letter of protest against the introduction of ‘Afrikaans’ to the Apartheid Minister for Bantu Education. The Minister’s response came on 8 June: the police raided his school, Naledi High, in order to arrest him. The police did not succeed in arresting him because of his fellow students’ resistance. He fled but was shortly after arrested just before the 16 June demonstration against the introduction of ‘Afrikaans’.

On 12 June Tsietsi Mashinini (chair of the SASM branch of the Morris Isaacson High School) formed an action committee with leaders from other schools. They decided to organize a mass demonstration on 16 June of all high school students in Soweto.

On 16 June the crowd of 12 to 16-year-old young people gathered in the early morning. They carried cardboard signs with the slogans: ‘Down with Afrikaans’, ‘Afrikaans is the oppressor’s language’, ‘Blacks are not dustbins’, ‘Viva Azania’. The atmosphere was relaxed. The national anthem was sung, people shouted Amandla (Power) with raised fists.

Not much later the police and army arrived armed with semi-automatic guns, batons and teargas. Without prior warning they sprayed teargas into the crowd. The responsible colonel J. Kleingeld shot with a machine gun at close range. The 13-year-old Hector Pieterson was one of the first deadly victims. The iconic photo in which Hector, fatally wounded, is carried away by a fellow student became worldwide the symbol of the Soweto uprising.

Soweto exploded. The attacked students reacted furiously. They threw stones to the police and army. The by the regime subsidized beer halls were attacked as well as liquor stores and shops operated by white people. The police and army shot at random at the students who did not stand a chance.

In the afternoon the crowd increased to more than 30,000 people. Unemployed youngsters joined the demonstration. Parents returning from their work found wounded and killed children. They also joined the protests. Soweto was isolated from the outside world. Only troop reinforcements were admitted. The next day the students continued attacking white stores. Thousands of people did not go to their work. A branch of Barclays Bank was burnt down. ‘Why kill kids for Afrikaans?’, a protest sign said.

According to SSRC leader Majakathata Mokoena 2,000 to 3,000 students were killed that day. Mokoena: ‘I was the one who had to list the missing, dead and arrested persons ’.23 Detainees, including children, were subjected to several forms of torture. This ranged from applying electric shocks to all parts of the body to making people sit for hours on an imaginary chair and attaching heavy weights to testicles. The corridors of the police stations were littered with dead and injured people.

Oshadi Mangena, working for the Christian Institute (CI) and BCM member, was one of the arrested persons on 16 June. She later fled her country and testified before the UN Investigation Commission: ‘By various means of torture they exerted pressure on me such as beating and electric shocks on my waist and breasts. I was blindfolded. I was also put into an electrically refrigerated bag and attached to an iron rod till I nearly choked’.24

Mutual solidarity

Ex-political prisoner (SSRC 11 trial) 25 Sibungile Mthembu Mkhabela tells looking back on the strong mutual solidarity in those days: ‘There was a tremendous discipline among students. All acted on the instructions of the SSRC and its leaders. There was close collaboration and people were prepared to listen to one another even though people belonged to different political movements. During the period of the Soweto uprising not a single black person got killed for collaboration [with the regime]. Nobody was necklaced.26 When the police used blacks from the hostels (barracks for black miners) to attack the community, the students went to the hostels and tried to explain to the residents they should not direct their anger against the community and that the police were responsible for the provocations. This action was very successful and as a consequence many supported the struggle of the students’.27

From the University of Witwatersrand white students staged a solidarity march to the centre of Johannesburg. Black workers and white bystanders joined the march: ‘Power to Soweto’. The police and white citizens attacked the demonstrators.

Several townships saw uprisings. Solidarity actions were organized at universities and schools. The protests also spread out to the countryside in the so-called homelands of Lebowa, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Qwa Qwa.

Meanwhile J.F. Visser of the police stated that they would proceed to deploy tougher methods to break resistance. The military was being organized and deployed. The police were totally free to act. Armored vehicles dominated Soweto traffic. A wave of murders started. Hundreds were arrested, even children of 8 were unscrupulously imprisoned. Order had to be maintained at all costs.

Thembile Ndabeni tells how in Cape Town the Apartheid regime and its police force hunted them down every single day: ‘We had to awake early every morning and hide away from the police. We hid in chicken shacks, gardens or pretend to be dumb or mentally ill just to avoid being harassed by the police. In some instances, we played with the ‘nice’ soldiers. Later we realised that the ‘nice’ soldiers were those who were forced into military conscription’. And : ‘We also had good policemen like Tata Majikela and others from the townships who refused to kill their children. They not only refused to obey instructions from their seniors but rejected white supremacy in its entirety’.28

The regime understood the protest was fundamentally aimed at the entire system of white minority rule. That meant a protest against the entire Apartheid educational system, starvation wages, poor housing, the Bantustan policy with its fake independence, the Urban Councils and other puppet institutions of the regime. These were the issues the BCM was fighting in the previous years. Mosibudi Mangena: ‘The Afrikaans issue , whilst very sensitive in its own right, was by no means a fundamental issue, but provided the spark that caused the whole conflagration’.29

Letter Enos Ngutshane at Naledi High. Pic. m.boelsma, 2015

Tsietsi Mashinini statue in Soweto. Pic. m.boelsma, 2015

Lid of garbage can used as a shield against the bullets from the police (Hector Pieterson Museum Soweto). Pic. m.boelsma, 2015

White response

Demonstration Rotterdam, 23 June 1976

Rotterdam, 23 June, 1976

Amsterdam, 28 August, 1976

For arms dealers the day after 16 June business was brisk. White private shooting clubs all of a sudden welcomed many new members. White students had to attend shooting lessons. White students from the University of Stellenbosch armed themselves.

Press coverage

Initially the killing of children was frontpage news in Dutch newspapers. Later coverage appeared on the inside pages. The tone and choice of words changed. In the language of the white regime there were now reports about vandalism, looting, rioting. The press proved to be blind to the similarities between Dutch resistance in WWII and black resistance in South Africa. In Azania Vrij30 it was pointed out that at the time also the oppressor’s symbols were attacked. Population Registries were attacked and windows of the NSB (National Socialist Movement) pubs were smashed.

Solidarity demonstrations Rotterdam and Amsterdam

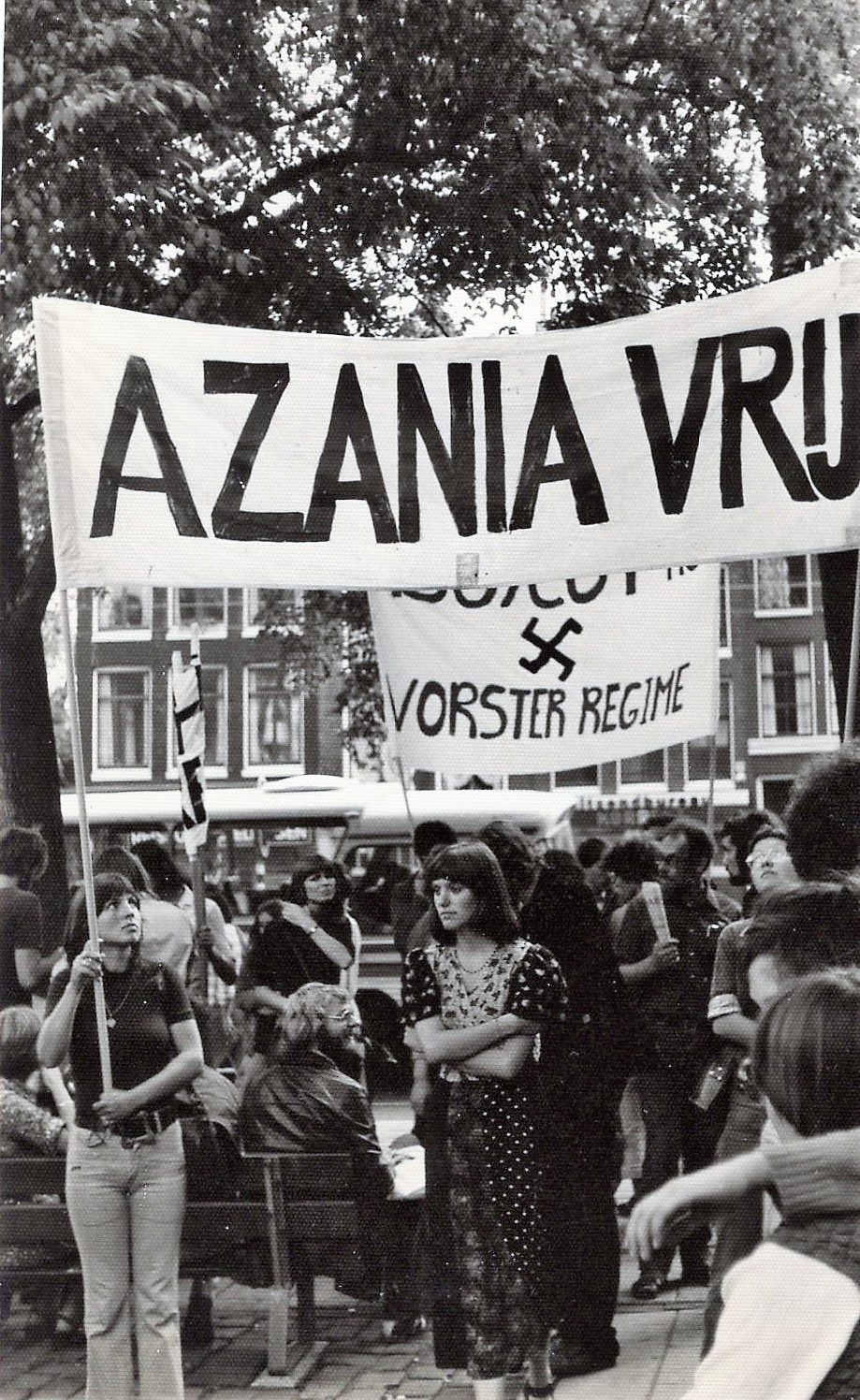

On 23 June the Azania Komitee31 organized a solidarity demonstration together with: Chili Movement Rotterdam, FNV (Trade Union), LOSON (National Organization of Surinamese in the Netherlands), PPR (Political Party of Radicals), PvdA (Labour Party), Palestina Komitee and Fair Trade Shops.32 Nyakane Mike Tsolo, PAC leader in Sharpeville 196033, said: ‘Dreamers still believe in peaceful change. There will never be a peaceful change in South Africa’. He emphasized the importance of unity among liberation movements.

On 28 August the AABN (Anti-Apartheid Movement Netherlands) organized a demonstration in Amsterdam. The Azania Komitee carried a banner saying ‘In solidarity with ANC, PAC and SASO’. It was forcibly torn away and damaged by their demonstration stewards. The slogan: ‘Viva Azania Boycott South Africa’ was deliberately drowned out by their megaphones. The AABN radically opposed any solidarity with organizations linked to the Black Consciousness Movement and the PAC. The name of liberation Azania (used by PAC and BCM) for South Africa was a curse to their ears.

Concession, growth of resistance

In July the regime reconsidered its decision to introduce ‘Afrikaans’ in education. It was up to teachers now to teach in English or ‘Afrikaans’. Students in Soweto organized themselves in the Soweto Students’ Representative Council (SSRC). All schools were represented. Tsietsi Mashinini was elected to be the first president. Parents organized themselves in the Black Parents Association (BPA).

The protesting students now concentrated on the South African economy: ‘We want to do what hits the enemy hardest’.34

Strikes

Early August about 20,000 people marched from Soweto to the headquarters of the security police in Johannesburg. They demanded the release of the political prisoners. Workers responded to the appeal to go on strike and join the demonstration. On 5 August SASO leader Mapetla Mohapi died in prison in suspicious circumstances.

On 23 August a three-day strike was called. About 150,000 to 200,000 black workers participated. Demands were the release of political prisoners, abolition of Bantu education and the overthrow of the Apartheid system. In September there were once more strikes in Johannesburg and Cape Town. In Cape Town economic life came to a near standstill. Three quarters of the workforce, about a quarter of a million workers, were on strike. Dockworkers, textile workers, construction workers and shop personnel joined the strike. In Johannesburg about half a million workers were on strike.

Forced exile

The regime started a manhunt and put a price on SSRC leader Mashinini’s head. In August he fled abroad. Khotso Seatlholo, 18 years old, replaced him as president of the SSRC. The organization went underground. In January 1977 also Seatlholo was forced to leave the country. He was replaced by Montsitsi, 19 years old. Because of the systematic terror many students fled the country. Usually Botswana or Swaziland were the first destination.

Kissinger

In September the American Secretary of State Kissinger visited South Africa. He met Prime Minister Vorster and Ian Smith, the Prime Minister of the white minority regime in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). His objective was to realize ‘stability’ in Southern Africa protecting western interests.

The black population considered this to be a strong encouragement to the Apartheid regime. He was received with vehement protests in no uncertain terms: ‘Kissinger Murderer’, ‘Kissinger go home’, ‘Kissinger get out of Azania’, ‘Don’t bring your disguised American oppression into Azania’.35 Again there were many deaths and injuries and many people were arrested.

Between 16 June and 31 October the police arrested about 4,200 people. Among them were prominent BCM leaders, including Steve Biko. Among those arrested were in particular black journalists and black trade union members. As these journalists lived in the townships themselves they could accurately report the situation. White journalists did not have access to the blocked townships. Hidden from the eyes of the world the regime could do anything it wanted.

Hundreds of young people were sentenced to lashes. During their pre-trial detention at least 12 prisoners collapsed under the torture of the police or suffered the rest of their lives as a result of physical and psychological torture. 36 The SSRC called upon people to use the Christmas celebrations in 1976 to grieve for the deadly victims of police violence. People responded overwhelmingly to the appeal.

In December 1976 an ANC representative asked the SSRC to only cooperate with the ANC. Khotso Seatlholo, on behalf of the SSRC, refused. The SSRC did not want to commit itself to one liberation movement. The refugee student leaders Seatlholo and Mashinini emphasized during a tour of the United States that the ANC, PAC and the students had a common enemy that had to be fought collectively. In 1979 Seatlholo en Mashinini formed SAYRCO (South African Youth Revolutionary Council) that would fight the regime with arms.

1977

Ban black organizations

Western countries

The uprising against the regime continued in 1977. South Africa implemented with determination its Apartheid policy with brutal repression and implementation of the Bantustan policy. Western countries expressed in particular their moral outrage over the harsh reality of the Apartheid regime. However, they did not jeopardize their political and economic interests.

In spite of a UN-arms embargo the United States, Great Britain and Italy supplied modern arms to South Africa totalling 7,5 billion Dutch guilders. Sean Gervasi revealed this in 1977 in the US House of Representatives.37

The Netherlands, for example, refused to sign the final declaration of the World Conference in Nigeria for Action against Apartheid. Minister Kooymans of Foreign Affairs did not agree with the section that Apartheid in Azania/South Africa ‘is based on expropriation, looting, exploitation and social exploitation of the African people since 1652 by colonists and their offspring’. 38 The Minister thought it unjust that in this declaration the entire Dutch community was addressed from the moment Jan van Riebeeck set foot on African soil. Today there is still very broad consensus for this view.

Invited by Harry Oppenheimer of mining multinational Anglo American Andrew Young arrived in South Africa in May. The Afro-American Young was UN Ambassador for the American President Carter. In South Africa he only spoke with businesspeople. He expressed his confidence that through free enterprise South Africa could be liberated.

The BPC refused to meet Young. He announced to speak with representatives of the SSRC. The SSRC had never arranged such a meeting and so did not show up. During the years that followed Western countries did everything in their power to make the regime abolish Apartheid by risk-free means. With their ‘constructive engagement’ they were particularly seeking to curry favour with black resistance in order to protect their strategic and economic interests.

At that time that ‘constructive engagement’ was unfavourably received. Winnie Mandela (ANC), for example, stated it would mean the black population had to give up the struggle. She spoke out in favour of the ‘Socialist Republic of Azania’.39 25 years later that ideal is a far cry from the policy of present-day ANC government.

Beginning Soweto Commemoration 1977

In the first step towards the first commemoration of the Soweto massacre the BPC declared the week of 20 to 27 March Heroes Commemoration Week. In this way they wanted to keep the memory of the Sharpeville Massacre on 21 March 1960 permanently alive.

In April the SSRC succeeded in preventing a rent increase of 40 to 80% in the townships with protest demonstrations. They also demanded to dissolve the Urban Bantu Councils (UBC). As an alternative the Committee of Ten stepped forward striving for democratically elected councils instead of regime-controlled UBCs. The members of the UCBs were considered collaborators who oppressed their own people.

Arrest SSRC leaders

On the eve of the Soweto commemoration the police arrested all SSRC leaders, including the president Dan Montsitsi. Nevertheless, the commemoration was held with the support of the BPC.

The arrested SSRC leaders were: Sechaba Montsitsi, Seth Mazibuko, Welile Twala, Mafison Morobe, Khotso Lengane, Sibungile Mtembu (Sibongile Mthembu Mkhabela), Thabo Ndabeni, Teboho Mngomezulu, Michael Khiba, Nkosinati Twala and Kennedy Mogami. The SSRC Eleven were charged with sedition and terrorism. Not until 1979 were the eleven sentenced to 4 to 8 years of imprisonment. Their ages ranged from 18 to 23 years. Sibungile Mkhabela, the only woman, had been in solitary confinement for many months. After her imprisonment a ‘banning order’ was issued immediately.

The number of political prisoners on Robben Island after the 1976 uprising increased from 253 to 383.40

Actions Soweto Commemoration

Tens of thousands of black workers answered the call for a strike on 16 and 17 June. Students and other political activists aimed their grievances at the Bantustan policy and racist educational policy. The regime spent 12 times more the amount of money on a white child than on a black child.

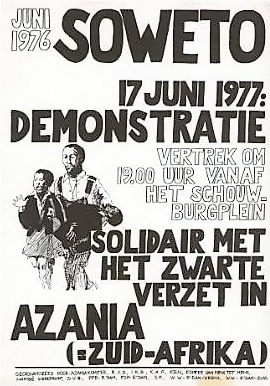

Soweto Commemoration Rotterdam

In Rotterdam on 17 June the Azania Komitee organized together with a number of other organizations a demonstration with banners saying ‘Vorster Murderer’ and ‘Boycott South Africa’. Afterwards Nyakane Tsolo (PAC) pointed out that a year after Soweto the flag of Apartheid still flies over the diplomatic relations also the Netherlands still has with the regime.

Poster Azania Komitee, 1977

Opposition Bantustan policy

In July, on the initiative of the BPC, black organizations met in order to organize opposition against the Bantustan policy. After Transkei the regime also wanted to grant ‘independence’ to the homeland of Bophuthatswana in 1977. It was decided unanimously to mobilize all black people in Azania against the so-called independence of the Bantustans. The slogan ‘One Azania, One Nation’ was aimed at the balkanization (compartmentalization in small non-viable regions) of South Africa by means of the Bantustan policy.

Death Steve Biko

On 12 September 1977 Stephen Bantu Biko dies in prison. Severe abusive behaviour by the police led to his death. In August the police arrested Steve Biko together with Peter Jones. The police forced them to stop their car at a roadblock. They were on their way to discussions to promote unity of resistance with the ANC, PAC and BCM. According to Biko there had to be one revolutionary movement fighting an unjust system. Biko: ‘I would like to see groups like ANC, PAC and the Black Consciousness Movement deciding to form one liberation group. It is only, I think, when black people are so dedicated and so united in their cause that we can effect the greatest results’.41

The anger about Biko’s death led to revolt and demonstrations nationwide. The funeral was attended by tens of thousands despite the efforts of the police to stop people from attending or to arrest them.

Carved in his coffin it said: One Azania, One Nation, One People – BPC- Steve Biko. The Netherlands and other Western countries sent official representatives to the funeral.

On 23 September the Dutch government suspended the Cultural Treaty with South Africa. A risk-free action with not a single consequence.

Ban organizations BCM

On 19 October all 18 Black Consciousness Movement organizations were banned. The Christian Institute led by Dr. Beyers Naudé was banned because it supported the BCM. The critical black papers The World and the Weekend World were prohibited to publish.

Among the banned organizations were political, cultural and student organizations. Some of these were: SASO, SASM, Black Community Programmes (BCP), Medupe Writers Organization, Zimele Trustfund, Black Women’s Federation (BWF), Union of Black Journalists (UBJ). Many political activists and black journalists were arrested, tortured and detained without trial.

International reactions

Minister of Foreign Affairs Max van der Stoel expressed his dismay that the South African regime had acted so drastically. The South African Ambassador in the Netherlands called for patience for a policy of gradual change by his regime…….

The Organization of African Unity (OAU)42 requested the UN to impose internationally binding economic and military sanctions on the Apartheid regime. France, Great Britain and the United States used their right of veto to obstruct this request. These countries, however, agreed on a binding arms embargo banning arms trade and military cooperation with South Africa. This embargo was in particular of symbolic value. South Africa already produced a major part of its own weapons.

Military technology was shared with countries such as Israel, Argentina (Videla), Taiwan, Morocco and Indonesia (Suharto). After the abolition of Apartheid Mandela awarded the coup leader, cruel occupier of East Timor and ‘the killer of communists in Indonesia’ Suharto with the Order of Good Hope.43 Suharto was awarded for his contribution to South Africa and financial support to the ANC. Later in the UN the Mandela administration abstained from the vote in which Indonesia was condemned for the annexation and occupation of East Timor, a former Portuguese colony.44

Reaction white minority

In the exclusively white South African parliamentary elections in November 1977 Prime Minister Vorster’s party, the Nasionale Party, won by a landslide. Never before had the Apartheid party obtained so many seats. Once again the white voters put their own interests above the injustice in which those interests are so deeply rooted. They expressed their full support for the brutal repression of Vorster with his fascist past.45

In the Netherlands fascists publicly supported the Vorster regime. On Human Rights Day, 10 December, fascists of the Netherlands People’s Union (NVU)46, led by Joop Glimmerveen, demonstrated at the South African Embassy to voice their support for ‘a white South Africa’. A counter-demonstration of anti-fascists, including the Azania Komitee, wanted to stop that. In order to protect the fascists the police cracked down hard on the counter-demonstrators. A number of injured protesters had to go to hospital for treatment. It was the first time after the war that there was a public fascist demonstration under police protection in the Netherlands. In those days the Ministry of Justice tried to ban the NVU. That failed. On the pretext of right to demonstrate the fascists freely take to the streets. Today fascist groups such as Voorpost and Pegida demonstrate in front of the South African Embassy against the ‘white genocide’.47

Refugees and liberation movements

After the Soweto uprising and the ban on the BCM organizations many left the country fleeing from the South African security police. The BCM in exile was set up. The former SSRC leaders Khotso Seatlholo and Tsietsi Mashinini formed the Black Consciousness youth movement SAYRCO.

Refugees joined the ANC, PAC, BCM or SAYRCO in exile. In 1960 after their ban in South Africa the ANC and PAC were now UN recognized liberation movements. The ANC had access to the largest financial resources thanks to support from the former Eastern Bloc and Western Anti-Apartheid groups.

ANC position

By the end of 1976 Director-General of BPC headquarters in Botswana, Harry Nengwekhulu, clearly spoke out against one-sided support for the ANC. According to him the ANC falsely claimed the Soweto uprising and appropriated a monopoly on information. This ANC monopoly on information and its supporters influenced, according to Nengwekhulu, the positions of Western governments. Breaking this monopoly to tell the real story of Soweto and the resistance was hardly possible. After the ban on the BCM organizations the ANC and related organizations urged from now on to solely support the ANC as the only liberation movement. The impact of this is still felt today.

The ANC criticized the Black Consciousness Movement and Steve Biko. In their official publication Sechaba 48 they wrote: ‘Our youth needs ANC revolutionary leadership’. They pointed an accusing finger at the BCM for disregarding cooperation with ‘all anti-racist groups irrespective of colour’. (…) ‘Thus the youth should discard the ‘go it alone’’. ‘To go it alone’ was a PAC slogan. The PAC and the Black Consciousness Movement were dismissed as racist. The ANC accused the ‘splinter movements’ of exploiting ‘the extremely racial character of our situation when appealing to the youth’. In reality both the PAC and the Black Consciousness Movement were and are committed to a non-racial society. However, given the fact of the existing unequal power relations of the colonial Apartheid system that was out of the question.

In Sechaba 49 Nkosazana Dlamini (former SASO leader) stated in 1977 that the Black Consciousness Movement leaders served the interests of Western imperialism. Soon after this publication Biko was arrested and tortured to death. After Biko’s death the ANC claimed him and posthumously exploited him for its own ends. When the film Cry Freedom 50 about Biko was released in the Netherlands, Dutch pro-ANC groups distributed pamphlets falsely linking Biko politically to the ANC-aligned UDF (United Democratic Front).51

Picket-line at South African Embassy in The Hague

At South African Embassy after bannings BCM organizations

Footage demonstration Human Rights Day, 10 December 1977 (Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms)

1978

AZAPO

In the years after the dramatic events in 1976 and 1977 the South African regime, in spite of fierce repression and reformist short-term solutions, did not succeed in containing black resistance.

In response to and following on the ban on black consciousness movements AZAPO (Azanian People’s Organisation) was formed in April 1978. Instantly several leaders and members were arrested. A number of them were issued with a ‘banning order’.

AZAPO recovered from the blow and launched organizations for young people (AZAYO), students (AZASM) and women (IMBELEKO). In the following years AZAPO dominated the public political struggle against the Apartheid regime. Tirelessly they fought for the international isolation of the regime. AZAPO led the fight for an international cultural boycott of the regime.

In the following years the South African regime tried by repressive means to eliminate AZAPO, its leaders and members. AZAPO members (and PAC supporters) were also at risk of being accused of collaboration by ANC/UDF supporters. Those accusations gave the ANC/UDF supporters an excuse to eliminate their political opponents.52 In its own way the South African regime was also involved in killings and fuelled opposition among the movements. ANC/UDF, AZAPO, PAC and other political opponents were among the victims of the regime.

Underground AZAPO had close contact with BCMA (Black Consciousness Movement of Azania) in exile and with its armed wing AZANLA (Azanian National Liberation Army).

Death of Sobukwe

In 1978 the leader and founder of the PAC, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, died.53 After his imprisonment on Robben Island he was put under house arrest in Kimberley. To this day a natural cause of death is seriously questioned.

Sobukwe’s funeral ended up in a widespread protest full of fighting spirit. Thousands of young Africans stood at the side of the roads to pay their last respects and attended the funeral.

Soweto commemorations

In the next years Soweto and Sharpeville commemorations54 were permanent on the agenda of black resistance at home and abroad. Prior to the second Soweto commemoration in June the police arrested nationwide between 2,000 and 3,000 people. The police went from house to house. Despite all this there was a mass gathering in the church of Regina Mundi, Soweto.

The Azania Komitee organized manifestations and demonstrations in Rotterdam, Breda, Nijmegen and Roosendaal in commemoration of Soweto. Majakathata Mokoena, member of SSRC leadership, gave an eyewitness account of the events in 1976. In December 1976 he had to flee his country.

Breda, June 1977

Breda, June 1977

Azaniaplein/Azania square

In commemoration of Soweto the Afrikaander square (Afrikaanderplein) in Rotterdam was symbolically renamed Azania square (Azaniaplein). Together with PPR Rotterdam, Galerie Solidair55 and Mike Nyakane Tsolo (PAC exile)56 the Azania Komitee paid tribute to the many who had died for the liberation of their country.

Rotterdam, June 1977. At the front Gladys and Mike Tsolo (PAC)

Political prisoners

In 1978 around 11 October, day of solidarity with political prisoners in Azania, the Azania Komitee organized rallies in Roosendaal, Breda, Tilburg en Rotterdam. Speakers were Majakathata Mokoena (SSRC) and Mike Ngila Muendane (PAC). The main focus of the rallies were the Soweto 11 and Bethal 18 trials.

Majakathata Mokoena (SSRC) and Ngila Muendane (PAC), centre Rita Grijzen (Azania Komitee, left Stoffelien Korporaal (Azania Komitee)

1979

Political trials

For their part in the preparation and organization of the Soweto uprising people stood trial for terrorism and conspiracy against the regime. Lengthy pre-trial detention with torture and prolonged solitary confinement preceded a trial. Some detainees did not survive their pre-trial detention.

SSRC Soweto 11

In 1979 the above-mentioned 11 SSRC leaders (the Soweto 11) were convicted. These young people were sentenced to 4 to 8 years’ imprisonment for organizing the Soweto uprising.

Bethal Treason Trial

The Bethal Treason Trial, one of the longest running trials against 18 PAC and BC leaders57, ended in 1979 with convictions for terrorism and conspiracy between 1963 and 1977. The ‘banned’ PAC leader Sobukwe was the first on the list of 86 co-conspirators. The state called 165 witnesses. The sentences ranged from 5 to 15 years on Robben Island. Main suspect PAC leader Zeph Mothopeng was sentenced to twice 15 years Robben Island. He and 2 other accused had been imprisoned on Robben Island before. Their ages varied from 21 to 66.

The trial took place behind closed doors. The press was refused access as much as possible. As a result of that and the anti-BCM and PAC attitude of the Anti-Apartheid organizations the names of the detained women and men and their brutal treatment remained hidden for the general public.

Picket-line at South African Embassy, 1978

The sentenced prisoners: 1. Zeph Mothopeng (65), co-founder of the PAC; 2. John Ganya (48), miner and underground PAC staff; 3. Mark Shinners (37), PAC leader in Pretoria; 4. Bennie Ntoele (38), PAC leader in Mamelodi; 5. Hamilton Keke (42), PAC leader Eastern Cape; 6. Sithembele Khala (24), Orlando West High School representative in Soweto at SSRC and active PAC member; 7. Alfred Ntshalinthsali (47), taxi driver and resident of Swaziland; 8. Julius Landingwe (29), BC member and organizer of NAYO; 9. Zolile Ghost Ndindwa (26), a BC leader in Cape Town; 10. Moffat Zungu (28), director of photography of the newspaper The World; 11. Mhlope Goodwill Moni (24), student leader in the Western Cape and PAC activist; 12. Jerome Kodisang (26), APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Army) guerilla skilled in Uganda, Sudan, Egypt and Libya; 13. Sello Mke Matsobane (36), PAC leader and founder of the Young African Religious Movement; 14. Johnson Nyathi (32), a long time PAC member and community leader in Kagiso; 15. Themba Hlatswayo (21), president of the SRC (Student Representative Council) in Kagiso and PAC activist; 16. Molatlhegi Tlhale (22), BCM student leader in Kagiso; 17. Rodney Tsoletsane (20), student leader in Kagiso; 18. Daniel Bizza Matsobane (31), SASO member and director of literacy programmes for adults at the Wilgespruit Fellowship Centre.58

From 1977 onwards the Bethal 18 were detained. During their pre-trial detention 4 PAC members were tortured to death: 1. Samuel Malinga, he maintained contact between PAC leadership abroad and Zeph Mothopeng in Soweto and Mangaliso Sobukwe in Kimberley; 2. Aaron Khoza, an ex-political prisoner and activist who worked with young people in Kagiso Township; 3. Dr. Naboth Ntshunsha, an underground PAC leader in Soweto; 4. Bonaventura Sipho Malaza, student leader at a high school in Kagiso.

Women freedom fighters Bethal Trial

Five women resistance fighters were subjected to the brutal treatment of the security service because they were regarded hostile witnesses and accomplices in the trial. Their names: Frozzy Shandu ka Mbatha, who traveled across the country with Saki Mafatshe, former Robben Island prisoner and political commissar at PAC HQ in Tanzania; Cindy Radley, a teacher at Alexandra High School; Lenah Mawela, beautician and model, responsible for recruit transport for military training abroad; Victoria Makheta commanded a special PAC underground communication unit and was forced to testify against her husband Moffat Zungu; Mado Dorcas Mosweu, active in the literacy programmes for adults and colleague of Dan Matsobane and Zeph Mothopeng at the Wilgespruit Fellowship Centre and Urban Resource Centre.59

No prosecution security police

The security police used veteran specialist and notorious torture experts for interrogating the defendants and potential witnesses. To this day none of these men60 has been held accountable by a court. Despite repeated requests, the ANC government refuses an inquiry into the practices of the security police (Special Branch) and to prosecute them.

Mahlangu (ANC) hanged

In 1977 Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu got arrested. He was an ANC freedom fighter, member of the armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe. In 1978 he was sentenced to death. Despite the international outcry, the sentence of death by hanging was carried out in 1979. Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu was 22 years old.

II

Anti-Apartheid

Call for exclusive support for ANC

Support for one of the liberation movements at the expense of others also had an impact in the Netherlands. After the ban on the organizations of the Black Consciousness Movement in 1977 the Dutch Anti-Apartheid organizations urged with one voice to exclusively support the ANC. They actually followed Craig Williamson’s (ANC member, later exposed as South African spy and murderer) advice. Williamson was Deputy Director of the IUEF (International University Exchange Fund).61 Initially, the IUEF supported all black political organizations in South Africa. After Williamson’s appointment the organization opted for exclusive support for the ANC as the one and only liberation movement.

In their monthly ‘Amandla’62 (May 1978) KAIROS (a Christian Anti-Apartheid organization), Boycot Outspan Actie (BOA) and Komitee Zuidelijk Afrika (KZA) argued in a series of articles that the decision to opt for the ANC made most sense. Never before had these committees been so explicit in their views. Previously the AABN had already declared to be in favour of exclusive support for the ANC.

Based on inaccuracies about the PAC and BCM they tried to win over public opinion. For example, Eggenhuizen wrote: ‘The PAC tries to operate nationalist African and therefore racist anti-white in South Africa’. He criticized the PAC for assuming a colonial situation in the country. He conveniently ignored the fact that the liberation movements ANC and PAC were UN-recognized as the legitimate representatives of South Africa/Azania. By now the regime in South Africa was illegal. Indeed, the liberation struggle went beyond just abolishing Apartheid. Due to the veto of the Western countries in the Security Council the illegal colonial regime could not be removed from the UN, but was treated as a pariah within the UN.

Bosgra (founder KZA) wrote: ‘In the Black Consciousness Movement and the PAC the prevailing simple concept is that the struggle in South Africa is a struggle between black and white’. Esau du Plessis claimed that the PAC was led and formed by reactionary anti-comminists. Du Plessis: ‘Even Robert Sobukwe, one of the main founders of the PAC (…) stated: ‘Marxists speak a foreign language in Africa’’. This quotation was completely taken out of context. Sobukwe answered the question whether the struggle against white supremacy implied that all white people were included. He said they are all shareholder of South African oppressive society Inc. They have an option whether or not to lose their share. According to him communism had been unfortunate in its choice of representatives in South Africa. The PAC has never considered the SACP (South African Communist Party), formed by white liberals, to be communist.

Sobukwe: ‘We do not hate the European because he is white. We hate him because he is an oppressor’. When asked whether he considered all white people to be oppressors he answered: ‘Once white domination has been overthrown and whites are not longer ‘the white boss’ but is an individual member of society there will be no reason to hate him’.63

Biko: ‘Some will charge we are racist but these people are using exactly the values we reject. We do not have the power to subjugate anyone. We are merely responding to provocation in the most realistic way. Racism does not imply exclusion of one race by another-it always presupposes that the exclusion is for the purposes of subjugation’.64

The writers in ‘Amandla’ and the ANC did not miss an opportunity to reassure white people as long as they embraced the ANC.

According to du Plessis the PAC slogan ‘Africa for the Africans’ proved that the PAC stood for a racist ideology. Du Plessis scornfully characterized the military wing of the PAC POQO (later APLA) as ‘a movement using random violence’ and, according to him, had a lot in common with the Mau Mau in Kenya. With these comments du Plessis disqualified both the anti-colonial uprising against British rule and Pan-Africanism.65

The white South African Bowey suggested in ‘Amandla’ (January 1981) that the PAC adopted a racist position.

The authors referred to in ‘Amandla’ embraced the Freedom Charter the ANC and related organizations are strongly based on. The Charter starts from the premise that South Africa belongs to all that live there. That means that the stolen land belongs to both the oppressor/occupier and to the oppressed expropriated. The adoption of the Freedom Charter was the basis to form the PAC for ANC members who did not subscribe to the Charter. The return of the land was a priority for the PAC. For that very reason the BCM also rejected the Charter. Lybon Mabasa, AZAPO leader: ‘The primary conflict in South Africa is that of land, and all attemps to reduce the struggle to one of civil rights or anti-apartheid can only buy time for those who wield power’.66

The ANC (and the SACP) ignore the historical fact that the land belongs to the black population. The BCM and the PAC on the other hand argue that the dispossessed, stolen land is to be returned. Only then there can be a non-racial society based on one man, one vote. The PAC argued that anyone who was loyal to Africa was an African. Sobukwe pointed out that ‘there is only one race: the human race’.

White solidarity?

Biko and Sobukwe believed that white South Africans needed to particularly get to work in their own white communities rather than interfere with the struggle of black people. Frank B. Wilderson III wrote that white left-wing people refused ‘to go against the concreteness of their communities, their own families, and themselves, rather than against the abstraction of ‘the system’’. 67 They put all their energy into Marxism and the black workers’ struggle but failed to organize the white working class against capitalism and racism.

The churches too found it hard to abandon their white positions. They were sharply criticized by the black community in South Africa: ‘We are sick and tired of those white Messiahs who martyr themselves abroad by talking about the suffering of the black people’.68 In the Netherlands this criticism fell on deaf ears. The Christian Anti-Apartheid organization KAIROS told the churches to opt for the ANC since the PAC was ‘too exclusively black’.

Biko remarked about the role of white people: ‘Not only have they kicked the black man; they have also told him how to react to that kick’. 69 Solidarity dominated by white people ends up in containing the black response to white oppression. The KZA reprimand to the newly formed ‘South Afrika In Exile’ (SAIE)70 is revealing.

SAIE had asked the Synod of the Reformed Church to support the entire South African liberation movement, so including the PAC and the BCM. The KZA did not like that. In March 1978 they wrote 71: ‘With some concern we observe some of your activities, for example your letter to the Synod of the Reformed Church of 10 February of this year. We wonder whether you realize the consequences of your position regarding support from the Netherlands for the liberation struggle in South Africa’.

The letter goes on justifying the exclusive support for the ANC. The KZA criticizes SAIE for ‘failing to understand political realities’ and ‘rabble-rousing’ in their decision to support the ANC. SAIE would ‘pose a serious threat to the liberation struggle as a whole’. The letter ends: ‘We urge you to seriously consider the negative consequences of your position’.

SAIE replied: ‘..it is extremely presumptuous to insinuate that people who have braved the bullets of the fascist police and who have spent time in the South African prisons because of their political commitment deal lightly with views about the national liberation struggle in our country. Your patronizing language is not only offensive, but also clearly racist for you claim that the struggle in which we are involved is too complex to be understood by blacks’.72

In the years after the Soweto uprising there was a boom in international conferences against Apartheid. Western white (subsidized) Anti-Apartheid groups and groups from the former Eastern Bloc countries dominated the stage. Black solidarity groups were barely given an opportunity to present themselves. They had fewer financial resources. White people presented themselves as experts, became institutions set in concrete, who complacently congratulated themselves and who tolerated no opposition.

An example is the International NGO Conference for the independence of Namibia and the eradication of Apartheid, held in Geneva, July 1984.73 Apart from the Azania Komitee KZA, BOA, AABN and KAIROS had been invited. All these organizations from the Netherlands were expected to choose one representative from among themselves who could address the conference. For the pro-ANC organizations it was inconceivable that the Azania Komitee representative could speak also on behalf of them. Nor did the Azania Komitee want to be represented by them. After much pleading the organization allowed the Azania Komitee to address the conference in spite of the opposition of the other Dutch organizations.

The Azania Komitee discussed the relevance of South African resistance in the country itself and the inaction of the international solidarity organizations. In those days the South African regime took harsh repressive measures against AZAPO, the only legally operating black resistance organization in South Africa. Members and leaders were arrested, offices trashed etc. The international solidarity organizations remained silent. The Azania Komitee asked the participants why. Was it about their criticism of AZAPO being racist because they were allegedly anti-white? Was their concern for the white South Africans inherent to their own white position and the same arrogance which is part of the oppression? The conference room and the chair remained silent.

In conclusion, the Azania Komitee asked the solidarity organizations to support the struggle of the people of Azania and its organizations in its entirety rather than to attribute a favorite role to or characterize as authentic one or other person or organization. The solidarity organizations ought to provide as much as possible correct and balanced information. It was important to avoid the struggle being dictated by external opportunistic and sectarian manoeuvres.

The speech of the Azania Komitee was not included in the report of the conference. 74

A year later a similar conference was held in Geneva. The representative of the International Union of Students (Burkhard Hermann) admitted to the representative of the Azania Komitee never to have heard of the PAC or the BCM. ‘Sharpeville and Soweto, yes, but was that not ANC? Puzzled and as a Czechoslovak member of the DDR (former East Germany) secretariat of his organization he asked me to send some information to Prague’.75

Impact one-sided support

The Soweto uprising generated worldwide support and sympathy. The solidarity organizations saw an increase in members and sympathizers. In the Netherlands the organizations received funding and evolved into established institutions. They exerted a great deal of influence on the media, political parties, relief organizations, cultural organizations and trade unions.

The media had only white correspondents in South Africa and the rest of Africa (which is now still the case). In 1986 the Ghanaian journalist Cameron Duodu wondered why. Was it because it was assumed that white journalists would report more objectively? He concluded that virtually the entire white press was racist.76

The dictate of these Dutch solidarity organizations who should or who should not receive support implied that radical liberation movements such as the BCM and the PAC did not receive any.

The approach of the Anti-Apartheid organizations was actually in line with US policy. In 1978 the Rockefeller Foundation scheduled a study committee to advise American policy on South Africa.77 The final report warned of the growing influence of the former Soviet Union on the ANC. The politically strategic and business interests (access to South Africa’s resources) of the US would be best met by ‘sharing with all races’ political power in South Africa. And subsequently the Foundation supported the ANC. After that, Arundhati Roy wrote, ‘the ANC turned against the more radical organizations such as Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement and pretty much eliminated it’.78

This interference from several sides in the liberation struggle had a significant impact on the non-ANC aligned organizations and their members. They were hit in many ways and led to life-threatening situations.

The authors of Biko Lives write about the violence between AZAPO and UDF (ANC aligned): ‘This violence has not been accounted for, nor has the role played by international solidarity organisations in the weakening of the BCM. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) did not have hearings on these atrocities. It is a well-known but unspoken fact that in places like Bekkersdal township in the North West province and Wallmer in the Eastern Cape lie the graves of dozens if not hundreds of BC movement members who were killed because they dared to say Biko is our father. So too the role of external interests in promoting one section of the liberation movement while denigrating the other still cries out for analysis and documentation’.79

In the ‘80s discussions took place between the UDF and organizations of the multinational mining company Anglo American.80 These were preparations for the situation after the abolition of Apartheid in which the interests of the large companies would not be infringed upon.81

Exclusive financial support for ANC

Financial support or withholding it were important tools to monitor and control the course of the liberation struggle.

In his thesis Aan de goede kant; een geschiedenis van de Nederlandse anti-apartheidsbeweging 1960-199082, Roeland Muskens investigated, among other things, how Dutch and European funding of projects of the resistance movements in South Africa and abroad were organized and manipulated.

NGOs such as the Protestant ICCO and the Catholic Cebemo spent between 1979 and 1990 79 million guilders on projects in South Africa. These projects were partially co-financed by the Dutch government. The government wanted to encourage social developments in South Africa in order to implement peaceful reforms. In addition humanitarian aid was given to the victims of Apartheid. In 1978, for example, the ANC and the PAC received half a million guilders for refugee aid. Between 1985 and 1990 Foreign Affairs spent 66 million guilders and even more through NGOs. These funds were mainly channeled to ANC projects.

Since the late ‘70s Sweden annually donated 7.5 million guilders directly to the ANC. The KZA wanted the Dutch government to follow that example. It did not come to that. However, through indirect channels a lot of money was raised for the ANC.

Since 1986 there was an option for the EU (European Union) to co-finance. This is how in 1987 the KZA received 3.5 million guilders for ANC projects in South Africa and abroad. In 1988 and 1989 they received 4.3 and 5.1 million respectively. After 1989 the level of the amounts decreased. In 1990 it was 5.1 million, in 1991 it was 3.4 million, in 1993 1.8 million. In 1994 the amount was higher: 3.2 million, of which 2.8 million was for the election campaign of the ANC. With these amounts of money the KZA was worldwide the largest private financial donor of the ANC.

In 1983 the ANC-aligned UDF was formed. In 1984 NOVIB (now Oxfam) financially supported the UDF with 100,000 guilders and in 1985 with 350,000 guilders. In 1987 the UDF’s annual budget amounted to 2 million rand and had more than 80 fulltime employees. Together with the affiliated organizations they received 200 million rand in the same year.83 It was pointed out cynically that because of the fact there were relatively many white people in UDF leadership it generated a lot of money from white people.

In 1986 the money spent on projects in South Africa amounted to a total of 6,750,000. Muskens writes that in the second half of the ‘80s it was even hard to find projects for all the available money. There was even a competition with the Scandinavian countries who would win the best projects.

EU

Pro-ANC activists manipulated the EU to direct funds exclusively to the ANC. Paul Staal (KZA) and David Sogge outlined to Muskens how it worked.

Together with the Reverend Beyers Naudé Paul Staal figured out that the financial support would be mainly channeled through the South African development agency Kagiso Trust, the SACBC (South African Catholic Bishops’ Conference) and the SACC (South African Council of Churches).

‘According to Staal the entire strategy was devised by Beyers Naudé and himself, and next superbly promoted to the European civil servants by Naudé and Tutu. Staal: ‘The masterplan was that EC-funds would go directly to the ANC and its affiliated organizations, so not diverted to the Inkatha Freedom Party of Buthelezi. In Europe especially the Thatcher government was keen that Buthelezi would get his share of the money’’. Staal continues: ‘Beyers and I had figured out that the SACBC, the SACC, the trade unions and the Kagiso Trust would select the projects. These parties were beyond any doubt, but moreover they were strong supporters of the ANC. Brussels was easily fooled and in this way both Buthelezi, the PAC and the BCM were excluded’.84

According to David Sogge 85 it was ‘clear from the outset – also for the European civil servants – that the money would go to ANC-aligned clubs. That was the whole idea. There were some small exceptions: NACTU [PAC trade union, Roeland Muskens] received some money and another project was the support for the organizations for South African SME employers, the NAFCOC. That was to accommodate the liberals in Europe. Inkatha was one of the parties that was invariably excluded. In particular the Thatcherites were strong supporters of Buthelezi. But ultimately it was just a fact that the money was intended for ‘left’. And ‘left’ meant the ANC. Also the PAC was virtually excluded from these funds. Ground for PAC to conclude: ‘…. money flows in a one-way ideological direction’’.

Muskens: ‘Between 1986 and 1994 overall more than 450 million ECU [precursor of the Euro] was spent as part of the Special Programme of the EU. That makes it one of the largest development programmes the EU has ever funded for one single country. The scale of the programme is particularly remarkable as it was not based on any European legislation. It was an additional programme, which not the Commission or the Council of Ministers decided on, but the European Parliament. The larger part of the money was spent straight away through the Kagiso Trust and the Catholic and Protestant churches in South Africa. Combined European NGOs have channeled funds totalling 127 million ECU. The Dutch participants accounted for slightly over one-fifth: Hivos (3.4 million ECU), ICCO (4.4 million), Cebemo/Vastenaktie (6.2 million), Novib (6.9 million) and the KZA (7.6 million). It was especially profitable for these organizations because they could deduct 6 per cent (later revised to 5 per cent) from these amounts of money for overhead. As the reporting requirements were minimal and, moreover, the South African partners selected the local projects and maintained contact, the relief organizations earned huge sums of money from EC-aid to South Africa’.

Outcome

The Anti-Apartheid organizations and the Western countries achieved their goals. The ANC won the first general elections in South Africa in 1994. Their candidate Mandela became President. Apartheid was abolished. The rest remained the same. No return of the land, no nationalization of the resources (South Africa is the largest producer of platinum and is in the top three of the gold, diamond and chromium trade) and no reparations. Capital remained in the hands of the whites. After 43 years the ANC is still in power and the country is one of the most unequal countries in the world. Recent figures indicate that 40% of the young people between 15 and 34 years old are unemployed or do not attend school.86

Arundhati Roy: ‘Today in South Africa, a clutch of Mercedes-driving former radicals and trade unionists rule the country. But that is more than enough to perpetuate the myth of black liberation’.87

III

Unwanted and unwelcome historical facts

Heritagization and museumification resistance

In Vilakazistreet in Soweto the history of political activism and confrontation with the regime merge. The street, where the Nobel Peace Prize laureates Tutu and Mandela lived, has become a tourist attraction with recollections and a disputable interpretation of a militant past.

Dr. Luvuyo Dondolo 88 takes Vilakazistreet as an example of heritagization and museumification of the past. He shows how the ruling ANC disposes of inconvenient and unwelcome historical facts. He compares it with the grand narratives of colonialism and Apartheid based on historical falsification and the myth of white superiority and nationalism. Dondolo: ‘The ANC narrative of the past is not different from the white colonial and apartheid narratives in terms of approach and conceptual framework.89

As an example, he describes how the history of the uprisings in Sharpeville (21 March 1960) and Soweto (16 June 1976) is presented in this street from the dominant ANC perspective. For example, they show a picture of Mandela burning his ‘dompass’ relating to the protests against the Pass laws in 1960 which led to the Sharpeville Massacre on 21 March. No reference is made to the PAC and Sobukwe, the organizers of the protest.

21 March (Sharpeville 1960) has been declared Human Rights Day since the abolition of Apartheid. Dondolo: ‘The day has been de-politicised and de-historicised. In this central account, the Sharpeville massacre is overshadowed by the memory of it as the place where Mandela signed the new Constitution in December 1996. The Sharpeville massacre is replaced by a post-1994 event in the making of the ‘new’ South Africa’.

The curatorial information about the Soweto uprising neglects, if not erases, the role of the BCM and the PAC and their leaders in favour of the ANC.

16 June was declared Youth Day. Although the two dates, 21 March and 16 June, have been designated as national days of commemoration and celebration, Sharpeville and Soweto as symbols of resistance have been historically grossly misrepresented.

Apartheid education with its colonial past still impacts greatly current education and society 25 years after the abolition of Apartheid. Inspired by the Soweto uprising today’s new generation of students and teachers continues to deal with the persistent legacies.

The simplified Mandelisation 90 of the complex history of the liberation struggle from the ANC perspective is a traumatic insult to the fighters and victims who were not ANC-aligned. The established Anti-Apartheid movements are jointly responsible for that. During the struggle against the Apartheid regime these groups also stimulated this ANC perspective by marginalizing, and even criminalizing, the BCM, the PAC and others. Destructive ‘solidarity’ has inflicted unnecessary pain and damage upon many, already traumatized by the South African regime.

Now, 25 years later, abolition of Apartheid has not significantly affected the power and ownership relations. The return of expropriated land and decolonization have dissolved in the mirage of Anti-Apartheid.

© Marjan Boelsma, August 25, 2019.

_________________________________________________

Special thanks to Patricia Schor and André Kaïjim for their constructive comments and valuable additions.

English translation: HippoLingo

©Pictures: Azania Komitee, Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms, Jan Warner.

Reproduction of articles or parts of articles is authorized, provided the source is acknowledged and that passages and quotations are not placed in a different context.

Notes

[1] Soweto was by Apartheid law a township for black residents. Townships functioned as ‘agencies of oppression and white supremacy’, Luvuyo Dondolo in Apartheid spatial plan: Heritagisation and museumification of the past at Vilakazi Street in Soweto’. From Reversing Urban Inequality in Johannesburg. Edited by Melissa Tandiwe Myambo, (London, Routledge, 2018)

[2] ‘Afrikaans’ evolved from the language of the Dutch settlers in the 17th century

[3] Azania is the liberation name for South Africa. The PAC and the BCM use this name. The ANC preferred the name ‘South Africa’

[4] Zeph Mothopeng was in 1959 one of the founders of the liberation movement PAC (Pan Africanist Congress)

[5] Steve Biko, ‘White Racism and Black Consciousness’ in I write what I like, a selection of his writings, edited with a personal memoir by Aelred Stubbs C.R. (London, The Bowerdean Press, 1978)

[6] Africans are the original inhabitants of South Afrika. The ‘Indians’ were transported as contract workers by the British to South Africa. ‘Coloureds’ are of mixed origin. According to segregation of the Apartheid system was hierarchically the white minority on top, then the ‘Indians’, next the ‘coloureds’ and the Africans as the lowest group in the racial hierarchy.

[7] Also called Homelands

[8] Part 1 Sharpeville https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/ and part 2 https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/10/30/history-sharpeville-part-2/

[9] POQO was the predecessor of APLA, the armed wing of the PAC

[10] From January 1963 to December 1965 there were nearly two hundred political trials involving more than two thousand defendants Many were imprisoned without a trial. On average 2 Africans a week were hanged. Most hanged men were POQO members. Ernest Harsch, South Africa: White rule, black revolt. (New York, N.Y. Monad Press for Anchor Foundation, 1980).

‘More PAC activists hanged in 60s’ https://www.iol.co.za/the-star/more-pac-activists-hanged-in-60s-1198105

[11]Ernest Harsch, South Africa: White rule, black revolt. (New York, N.Y. Monad Press for Anchor Foundation, 1980)

[12] ibid

[13] ibid

[14] Mangena, after having served his sentence, went into exile and became BCMA chair

[15] Part 1 Sharpeville Sharpeville https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/ and part 2 https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/10/30/history-sharpeville-part-2/

[17] https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/abram-ramothibi-onkgopotse-tiro ‘towards the end of 1973 he found out that the police were planning to arrest him and he fled to Botswana, where he played a leading role in the activities of SASM, SASO and the BPC. While living a simple life at the Roman Catholic Mission at Khale, a village about 20km from Gaberone, he was instrumental in forging links with militant revolutionary groups such as the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) in 1973’

[18] https://mayihlome.wordpress.com/tag/onkgopotse-ramothibi-abram-tiro/ on Tiro’s assassination and who were responsible

[19] ‘In October 1975, another mass bus boycott began, this time near the steel town of New Castle in northern Natal. For four weeks, up to forty thousand black industrial workers walked from eight [13 kilometers] to fourteen miles [23 kilometers] to and from work each day between New Castle and the townships of Madadeni and Osizweni, both located within KwaZulu’. Ernest Harsch, South Africa: White rule, black revolt. (New York, N.Y. Monad Press for Anchor Foundation, 1980)

[20] Azania Vrij 1976 no. 5/6

[21] Steve Biko, I write what I like, a selection of his writings, edited with a personal memoir by Aelred Stubbs C.R. (London, The Bowerdean Press, 1978)

[22] The Bantustan or homelands policy meant that the regime divided 13% of the country into 9 Bantustans for the black majority. Each one would allegedly be granted independence. The residents became against their will citizens in the territories allocated by the regime. In October 1976 Transkei was the first one to be declared independent. 44% of these residents worked in the mines and white urban areas. Transkei did not have a viable economy and consisted of large parts of infertile land. In reality the homelands were reservoirs of cheap labour and a dumping ground for non-productive black people such as the elderly, the sick and children. Transkei’s independence was not internationally recognized. The banned liberation movements ANC, PAC and the then legally operating Black Consciousness Movement vigorously rejected the Bantustan policy.

[23] Interview met Azania Vrij, no. 4, 1978

[24] Azania Vrij 6/1- 1977/78

[25] Soweto Students’ Representative Council

[26] In the ‘80s suspected collaborators with the South African regime were killed by means of necklacing

[27] http://disa.ukzn.ac.za/sites/default/files/pdf_files/ora19940818.000.009.000.pdf

[28] http://mayihlomenews.co.za/the-1976-students-uprising-in-cape-town/

[29] Mosibudi Mangena, On your own: Evolution of South Africa/Azania (Braamfontein, Skotaville Publishers, 1989)

[30] Azania Vrij archive IISG

[31] The Azania Komitee was formed in October 1974 with the objective of supporting the liberation movements in South Africa/Azania in their struggle against the colonial Apartheid regime. For more information https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/english/ https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/13/apartheid-antiracisme-dekolonisatie-2/

[32] Chili Movement Rotterdam, FNV, IWOZ, KONDA, LOSON, Namibia Working Group, Nivon Youth Members, Palestina Komitee Rotterdam, OVB, PPR Rotterdam, PSP Rotterdam and Schiedam, PvdA, Fair Trade Shops Rotterdam Zuid, Capelle a/d IJssel and Alexanderpolder, KAO

[33] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/

[34] John Kane-Berman, South Africa: The Method in the Madness (London, Pluto Press, 1978)

[35] Cape Times, 18/9 1976

[36] Ernest Harsch, South Africa: White rule, black revolt. (New York, N.Y. Monad Press for Anchor Foundation, 1980)

[37] See also http://psimg.jstor.org/fsi/img/pdf/t0/10.5555/al.sff.document.nuun1978_27_final.pdf

[38] http://psimg.jstor.org/fsi/img/pdf/t0/10.5555/al.sff.document.nuun1977_30_final.pdf

[39] Swedish newspaper Expressen, 1977, 31 March

[40] Azania Vrij, 1977, no.3/4

[41] Steve Biko, Our Strategy for liberation in I write what I like, a selection of his writings, edited with a personal memoir by Aelred Stubbs C.R. (London, The Bowerdean Press, 1978)

[42] Since 2002 African Union (AU)

[43] https://mg.co.za/article/1995-05-26-mandelas-strange-links-to-human-rights-abuser . Arundhati Roy, Capitalism: A Ghost Story (Verso Books, London, 2014)

[44] https://www.theguardian.com/world/1999/jun/17/southafrica.nelsonmandela

[45] Vorster was a prominent figure within the fascist organization Ossewabrandwag. During WWII he was in prison for his fascist ideas

[46] https://kafka.nl/nederlandse-volksunie-nvu/

[48] Sechaba, third quarter 1976 http://www.disa.ukzn.ac.za/sites/default/files/pdf_files/sejul76.pdf.

[49] Sechaba 2, 1977 (printed in the GDR)

[50] Controversial film adaptation of the controversial book by Donald Woods about Biko. Both the film and the book did not properly reflect Biko’s policy and life according to BCM critics

[51] In June 1983 organizations that felt affinity with the Black Conscious Movement and the PAC formed the National Forum. Then in August, as a counterbalance, the ANC-minded UDF was formed

[52] Andile Mngxitama, Amanda Alexander, Nigel Gibson, Biko Lives! Contesting the legacies of Steve Biko (New York, N.Y. Palgrave MacMillan, 2008)

[53] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/

[54] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/ and https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/10/30/history-sharpeville-part-2/

[55] Galerie Solidair was owned by the artists Ro Heilbron and Wim Gerritsen.

[56] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/2018/05/03/sharpeville/ Tribute to Mike Nyakane Tsolo.

[57] http://mayihlomenews.co.za/the-secret-bethal-treason-trial-revisited/

[58] ibid