Solidarity with the liberation struggle in Azania/South Africa and fight against racism in the Netherlands, 1975 – 1992

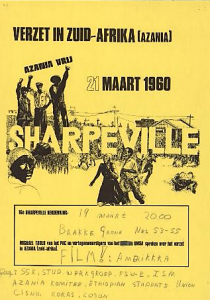

The second part of History Sharpeville continues with a survey of Sharpeville Commemorations in the Netherlands with an account of the events in South Africa/Azania and the commemorations there. The first Sharpeville Commemoration (1975) by the Azania Komitee is described in part 1.

Before describing the following years first an impression of the position the AABN (Anti-Apartheid Movement Netherlands) adopted towards solidarity with the liberation movements in South Africa/Azania. The AABN and other organizations(1) supported only ANC (African National Congress) because in their view this was the best organization for the liberation of South Africa. Organizations such as PAC (Pan Africanist Congress), Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) and related organizations were considered to be anti-white and too radical.

Anti-Apartheid Movement Netherlands concerned about visit PAC

The AABN watched with suspicion Maphumzana David Sibeko’s visit to the Netherlands in 1975 for the first Sharpeville Commemoration organized by the Azania Komitee(2). Sibeko, PAC representative, was known as the South African Malcolm X (3) Conny Braam, AABN, shared her concerns with ANC representative Reggie September: ‘In a letter to Reginald September Conny Braam reported in 1975 an “irritating little subject”, being the activities of PAC in the Netherlands. In the letter Braam informed him that PAC leader David Sibeko was in the Netherlands: “invited to the Netherlands by some dubious group in Rotterdam posing under the name of the Azania Committee”, to engage in “disruptive activities”. ’ Muskens, in his study Aan de goede kant, continued: ‘It was particularly disruptive because Sibeko’s appearances coincided with the AABN-campaign for the underground South African trade union.‘(4)

At that time ANC was hardly visible in South Africa. Bart Luirink (AABN): ‘Especially in the second half of the seventies there simply was no ANC in South Africa, so if you went all out for that club as a solidarity organization, you just had a difficult time.’(5) Researcher Muskens concludes: ‘In the seventies Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement was in South Africa a more visible and more appealing organization than the prohibited (and consequently absent) ANC. In fact young South Africans only heard about ANC from their parents. For militant South African young people ANC was primarily the organization of their parents. Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was more appealing. And also PAC – also prohibited – was probably more popular with young people in the townships than ANC at that time.’(6) In spite of this fact, the AABN and the solidarity organizations Komitee Zuidelijk Afrika, KAIROS and BOA did everything possible to support the more moderate ANC at the expense of the other liberation movements. Millions of guilders were raised for ANC(7) and in that way the outcome of the liberation struggle in South Africa was manipulated externally to propel ANC to power. This will be discussed in a later article.

Sharpeville is usually mentioned in the same breath as ANC activities by the Dutch press. PAC never got the credits they deserved. Later BCM did not fare any better.

The Azania Komitee organized for the representatives of the liberation movements that were in the country for the Sharpeville Commemoration talks with representatives from political parties, parliamentarians, government officials, church organizations, media, NGOs and other social organizations. It was one of the ways to gain political and humanitarian support for those liberation movements that were rather not heard or seen in the Netherlands by the support organizations of ANC.

1976

A left-wing administration with a ‘critical dialogue’

In this year the left-wing Den Uyl government was in office. The government adhered to a conservative course regarding Apartheid South Africa. Under the responsibility of Max van der Stoel, minister of Foreign Affairs, the government continued to follow a course of ‘a critical dialogue’ with the Vorster regime in Pretoria in order to change their mind. They had confidence in Vorster’s promises who had asked for time to undertake reforms. South Africa’s reality, however, was one of terror and war.

The Pass Laws still took a heavy toll on the black population of South Africa. Annually more than 100,000 people were arrested for violating the Pass Laws. In the year 1975 – 1976 the number of arrests increased to nearly 400,000. Meanwhile Vorster was also waging war against the newly independent Angola.

The ‘critical dialogue’ of the Den Uyl government was finally stopped after the Soweto Uprising of 16 June. Hundreds of peacefully protesting students were killed by the Vorster regime.(8)

Call for unity liberation movements

Around 21 March Sharpeville Commemorations were organized in Rotterdam and Amsterdam. Phillip Mokgadi (South African Student Organisation, West Germany), Nyakane Mike Tsolo (PAC Benelux representative), Scrape Ntshona on behalf of UMSA (Unity Movement South Africa) and Vuyani Mngaza (PAC representative in London) talked about the recent developments in South Africa and the urgency to build unity in the resistance movements. By the end of 1975 ANC, PAC and UMSA, under the auspices of OAU (Organisation of African Unity), in principle agreed to join forces. However, this project did not succeed.

In Rotterdam Fair Trade shops Vlaardingen and Rotterdam South, KORO (Communist Organization Rotterdam and Surroundings), Namibia Working Group and IWOZ (International Working Group Old South) had joined forces.

In De Brakke Grond, Amsterdam, the commemoration was organized in partnership with the SSK (Socialist Student Collective), working group South Africa with sociology and anthropology students, ESU (Ethiopian Students Union), CISNU (Confederation of Iranian Students National Union), KORAS and LOSON (National Organization for Surinam People in the Netherlands). The documentary AMERIKKKA, about the anti-racist and anti-fascist struggle in the United States, was shown.

1977

SASO/BPC trial

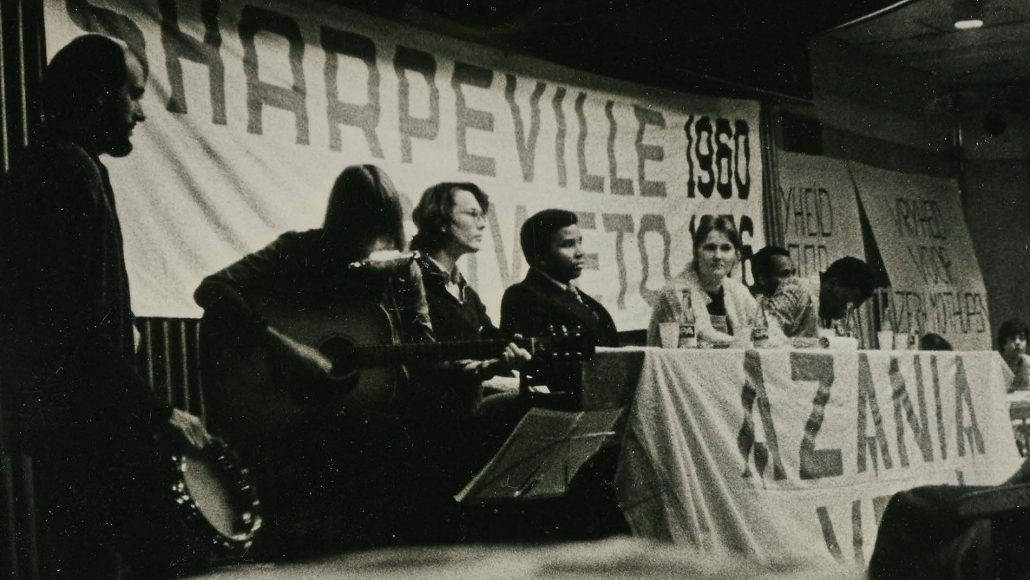

The Sharpeville Commemoration of 1977 took place in the dramatic aftermath of the Soweto Uprising of 16 June 1976, the subsequent repression and unaware of the dramatic events that would take place later that year: the killing of Bantu Steve Biko and the prohibition on organizations (a.o. SASO and BPC) of the Black Consciousness Movement.

In January 1975 the SASO/BPC trial started, in which 9 leaders of SASO (South African Students’ Organization) and BPC (Black People’s Convention) were facing trial. Steve Biko was an important witness for the defense. In December 1976 the 9 were found guilty in accordance with the Terrorism Act and were sentenced to 6 and 5 years’ imprisonment. They were immediately transported to Robben Island to serve their sentences.

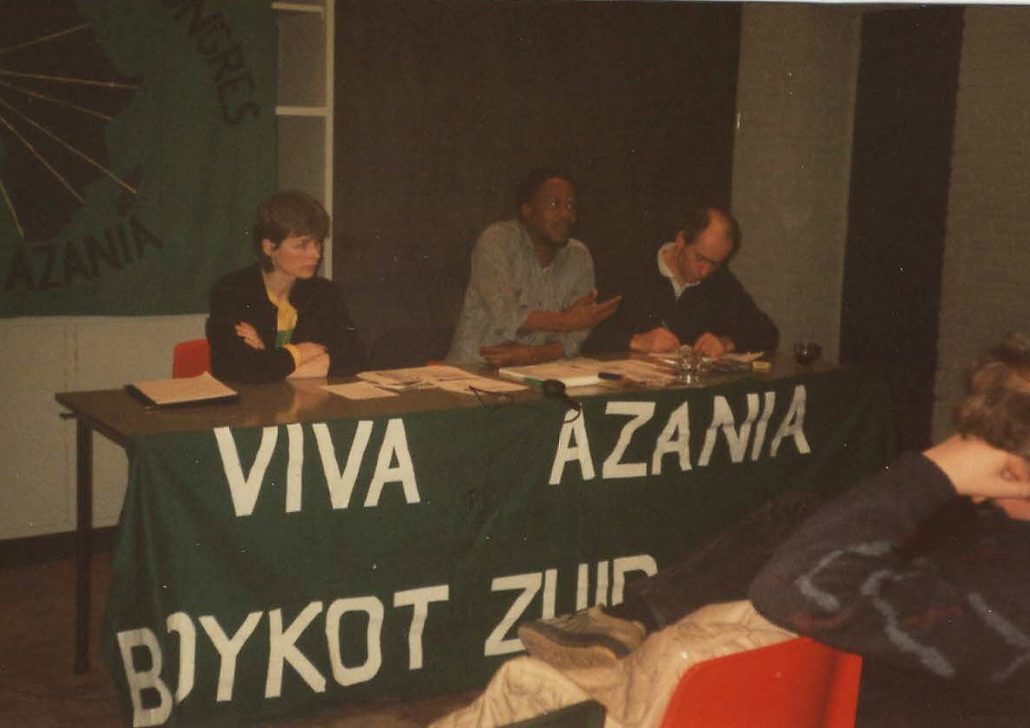

Viva Azania, Boycott South Africa

The Sharpeville Commemoration 1977 took place in Rotterdam with an afternoon and evening program. The commemoration was supported by the Zuidelijk Afrika Komitee The Hague, the Rotterdam section of the Partij van de Arbeid, KAO (Communist Labourers’ Organisation), Fair Trade shop South, Komitee Geen Racisme in de Sport (Committee against racism in sports), Namibia Working Group, Vereniging van Dienstweigeraars (Conscientious Objectors’ Organization) and the Anti-Vrijwilligersleger Komitee (Committee Anti-Volunteers’ Army).

Speakers were Lungelo Winston Mvusi on behalf of PAC and J. Makona on behalf of ANC (African Nationalists).(9) Drake Koka of the Black Allied Workers’ Organization (BAWU) was unable to attend. His contribution was read out. The short documentary Viva Azania, Boycott South Africa (Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms in partnership with the Azania Komitee) was shown and in it an eyewitness account by Nyakane Mike Tsolo of the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960.

International political poetry was performed by the Rotterdam worker poet Pierre van Vollenhoven and the Surinamese poet Romeo Grot. Poems of the BCM were read. A number of these poems was used as evidence in the SASO/BPC trial.

The Arbeiderskoor Morgenrood sang international militant songs. Part of the choir left the room under protest because the PAC representative, Lungelo Winston Mvusi, was critical of the Communist party South Africa, dominated by white members. The other part of the choir stoically continued their program. Remarkable was the presence of Esau Du Plessis with a booth of the Boycot Outspan Actie (BOA). He was not at all a supporter of the Azania Komitee and PAC.

The TV-news was present and recorded for broadcasting that night. The Commemoration took place on Sunday 27 March. Late in the afternoon there was the Tenerife air disaster involving KLM and 583 people lost their lives. Understandably the recordings of the Commemoration had to make way for the tragic news from Tenerife.

1978

Death of Mangaliso Robert Sobukwe, arms embargo and Bethal Trial

The Sharpeville Commemorations 1978 took place against a background of increasing repression in South Africa, international pressure on Vorster, the death of PAC leader Sobukwe and the right-wing Van Agt/Wiegel government that took office.

In December 1977 the trial of 18 leaders and members of PAC started in Bethal. The 18 were charged with organizing the Soweto Uprising in 1976. The trial lasted till 1979 and was the longest-running political trial in the liberation history of South Africa/Azania. The trial took largely place in secrecy. Four of the accused were tortured to death during their pre-trial detention.(10)

Late 1977 the UN Security Council imposed a binding arms embargo. Vorster was not impressed and made the white dominant position in South Africa sacred.

In the Van Agt/Wiegel government Van Der Klaauw (VVD) was appointed minister of Foreign Affairs and De Koning CDA) minister of Development Cooperation.

On 27 February Mangaliso Robert Sobukwe (54), first President of PAC, died (11) banned in Kimberley. He suffered from lung cancer. There are strong indications that he was poisoned by the South African regime during his imprisonment on Robben Island.

In the Netherlands South African exiles organized together with the Azania Komitee a memorial service in the Laurenskerk, Rotterdam. Among the many present were minister De Koning of Development Cooperation, the ambassadors of Kenia, Tanzania and Ghana. J. Voogd, PvdA MP, J.N. Scholten, CDA MP and Nyakane Mike Tsolo (PAC) spoke. The service was led by ds. R. J. Van der Veen and ds. Magubane.

Dutch government supports PAC humanitarian projects

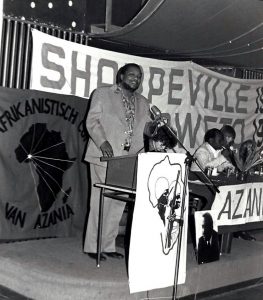

Maphumzana David Sibeko, principal PAC representative at the UN and central PAC committee member and Victor Mayekiso, central PAC committee member and Libya representative spoke at the Sharpeville Commemorations around 21 March. Maphiri Masikela spoke about the BCM.

In Tilburg, Vlissingen, Rotterdam and Amsterdam they spoke about and discussed the situation in their country and the opportunities for solidarity. Maphiri Masikela criticized the Anti-Apartheid Movements who were, with their liberal mindset, too busy speaking on behalf of the Azanians. What she meant was solidarity that was limited to only ANC and silenced other voices. Also white women who came to tell how (black) women’s lib should be accomplished were criticized by her.

An EPLF (the Eritrean liberation movement) representative in Europe showed his solidarity with the liberation struggle in Azania/South Africa.

Sibeko and Mayekiso were formally received by the ministers Van der Klaauw (Foreign Affairs) and De Koning (Development Cooperation). The Dutch government donated half a million guilders for PAC humanitarian projects.

1979

AZAPO, Botha, Zimbabwe

In October 1978 P.W. Botha succeeded Vorster as PM of South Africa. In 1978 the Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPO) was founded, a continuation of the prohibited BCM organizations. Right after the start the leaders and members had to face arrests and other repressive measures by the Botha regime.

Students of the Turfloop University in South Africa went on strike against the exclusion by the university of a student who had participated in a Sharpeville Commemoration.

Zimbabwe on the eve of independence

This time Sharpeville Commemorations were organized in The Hague, Amsterdam, Roosendaal, Breda and Rotterdam, together with the Zimbabwe Komitee.

Guest speakers were Henry Isaacs and Majakathata Mokoena. Isaacs was PAC foreign office secretary and UN representative. Isaacs came from the South African Students’ Organization (SASO) linked to the BCM. After his escape from South Africa he joined PAC.

Majakathata Mokoena was one of the leaders of the SSRC (Sowetan Students’ Representative Council) who led the student protests in 1976. On behalf of the ZANU (PF) (Zimbabwe African National Union, Patriotic Front) Teddy Nyahasha from Zimbabwe spoke on the eve of independence in 1980.

1980

Today Zimbabwe, tomorrow Azania!

Zimbabwe, the former Rhodesia, gained independence in 1980. The ZANU PF achieved a resounding victory in the elections of February. On 18 April Zimbabwe gained independence and the British returned the country. The ZANU PF was a sister organization of PAC. In June 1979 David Sibeko was shot in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. It is generally assumed that the South African regime was actively involved in his death.

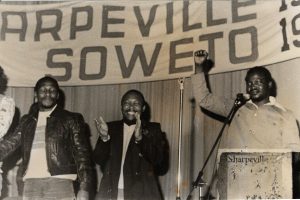

Together with the Zimbabwe Komitee and LOSON the Sharpeville Commemoration was organized in Rotterdam. Jonas Bungu of ZANU PF, one of the speakers, had been involved in the elections in Fort Victoria, by ZANU PF liberated territory. Both optimistically and militantly he concluded his speech with ‘Today Zimbabwe, tomorrow Azania!’

On behalf of PAC Zola Vimba, PAC representative in Nigeria and member of APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Army), the armed wing of PAC, spoke and Nyakane Mike Tsolo, PAC representative Benelux. Tsolo reaffirmed in his speech ‘that there was no intention of driving white people into the sea, but warned that when this white minority was not willing to accept a democratic government in Azania they had better leave the country by the same route they had entered it.’

Plans racist decentralization policy and immigration ban

Henry Does, chairman of LOSON, spoke, amongst others, about the immigration ban plans of Wiegel, minister of Home Affairs at the time. Does condemned the re-introduced racist dentralization policy that would destroy the Surinamese community. He observed that unemployment among Surinamese was four times higher than for the Dutch.

Messages of solidarity were sent out by a representative of the Central African Students’ Union and by a representative of the EPLF (Eritrean People’s Liberation Front) in the Netherlands.

Singer Walter de Buck, the music groups Ton Ton Brafoe and Redi Drom and the Bredaas Socialistisch Koor were responsible for the cultural program.

1981

Sharpeville Commemorations in South Africa

‘We don’t need no education, we don’t need no thought control’ are the famous words in the Pink Floyd song ‘Another brick in the wall’. In June 1980 this song was banned in South Africa for fear the song would become a song of liberation for black students.

Increasingly openly the memory of the Sharpeville Massacre and its importance were kept alive in South Africa. The Komitee van Tien, AZAPO and COSAS (Congress of South African Students) organized memorial services. The Komitee van Tien, led by dr. Motlana, consisted of prominent senior residents of Soweto. The Komitee had been set up in response to the student protest in Soweto, 1976.

In Sharpeville members of AZANYU (Azanian National Youth Unity)(12) cleaned the graves of the people killed, together with their relatives.

Boycotts and sanctions inadequate for total liberation

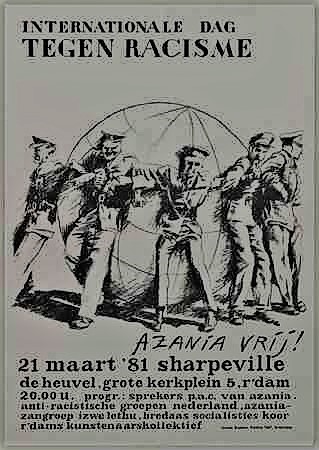

In the Netherlands the Sharpeville Commemoration was co-organized with the SSBS (Institution Social Interests Surinamese), ADA (Anti-discrimination group Alkmaar) and the Rotterdam Artists’ Collective.

Joe Moabi, PAC representative, pointed out that the essential purpose of racism in the western countries is to hide the exploitation of one person by the other. It is a misconception to believe there is only racism and Apartheid in South Africa. Moabi put into perspective the importance of calling for boycotts and sanctions. You cannot obtain power by inaction and making those appeals. The enemy might be weakened and that is helpful, but boycotts and sanctions will never result in total liberation. Moabi: ‘We believe we must face the enemy with arms, in our own country with our own people.’

Racism in the Netherlands

The ADA representative elaborated on discrimination and racism in the Netherlands and named as its victims foreign workers (the term ‘allochtoon’ was not used then), refugees, Surinamese and Roma and Sinti (named gypsies at that time).

Paul Middellijn, Surinamese poet and writer, reminded us of the Dutch colonial past and its impact for the present:

‘Een heleboel mensen denken

dat het alleen een ticket is

die Surinamers naar Nederland heeft gebracht

maar ze zijn

geschiedenis

hun schoolboeken

achterna gereisd

(..)

Nee, laat de Rijn mijn hoofd

Niet meer binnenstromen via

ons land

bij Lobith

Nee, noch via verwrongen gedachten en dogma’s

Nee, niet verder

Nee, niet nogmaals

Nee,

De rivieren van mijn land zijn….

Slagaders van mijn Sranan.’

A special highlight was the performance of the music group Izwe Lethu, with Philip and Zoey Mokgadi and their two sons. Philip Mokgadi was the PAC representative for the German speaking countries in Europe. The Bredaas Socialisties Koor wrote and performed this song:

Sons and daughters of Africa; fight for a free Azania; we call for solidarity; with unity in the struggle; Africa for the Africans.(13)

1982

UN Committee called for the release of PAC leaders serving a life sentence

The United Nations Special Committee against Apartheid declared 1982 as International Year of Mobilization for Sanctions against South Africa. At the same time the Committee called for the immediate release of six PAC political prisoners who were sentenced to life imprisonment and had already spent 20 years on Robben Island in 1982. They were the first to be sentenced after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 and to arrive on Robben Island. Of these six persons four of them were just between 15 and 17 years old when they were sentenced. Jafta Masemola, one of the six, had been in solitary confinement since 1968. The other prisoners were: Samuel Chibane, Philemon Tefu, Dimake Malepe, Isaac Mthimunye and John Nkosi.

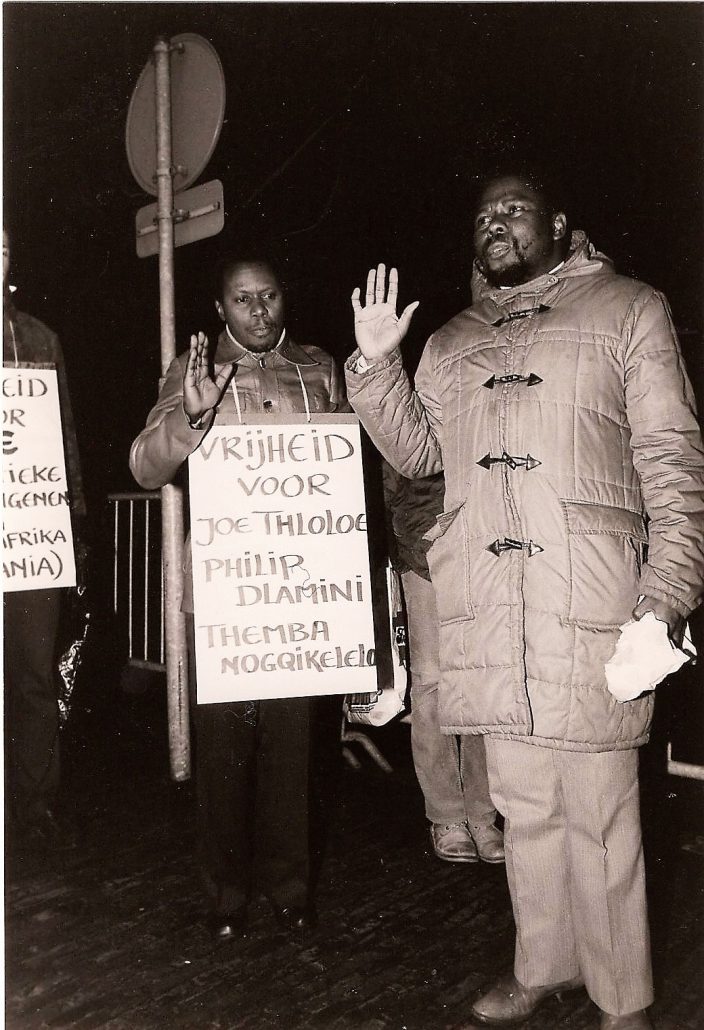

Picket line at the South African Embassy on 21 March

On 21 March the Azania Komitee organized for the commemoration of Sharpeville a picket line demo at the South African Embassy. Zolile Hamilton Keke, a former Robben Island prisoner and PAC representative in Europe, was one of the demonstrators and delivered a speech. The focus was on two PAC trials: the Bethal 18 and the trial due on March 22 of 9 PAC accused and on the release of PAC prisoners sentenced to lifelong imprisonment on Robben Island and all other political prisoners.

The Bethal trial took nearly 2 years and was largely conducted in secrecy. The 18 accused and the main suspect Lekoane Zeph Mothopeng were found guilty in 1979 of preparation of and involvement in the Soweto Uprising of 1976. They were sentenced to 5 till 35 years of imprisonment. During the trial 4 people were tortured to death during their pre-trial detention. Zolile was one of the accused. He was given a suspended sentence and was prohibited from engaging in political activities. After the sentence he fled his country.

In the trial of 9 PAC accused yet to start Thloloe, a prominent journalist, was the main suspect. Thloloe was previously sentenced to imprisonment for his part in the Pass Laws campaign ending in the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre. During the Bethal trial he refused to act as a state witness. Thloloe was a board member of the black journalists’/media workers’ association MWASA and had been forced into exile since 1981 until his arrest. As a result he could not work in his profession.

Another suspect was Philip Dlamini, secretary-general of SABMAWU (Union of Black Municipal and Allied Workers Union). He was previously sentenced to 18 months for refusing to witness against Lilian Keagile who stood trial under suspicion of ANC activities. Themba Nogqikelelo was one of the founders of AZANYU and also refused to testify in the Bethal trial. In 1980 he supervised maintenance of the graves in Sharpeville and fled to Botswana where in 1981 he was kidnapped by the South African police. The others that were standing on trial were: Sipho Nqobo, secretary-general AZANYU, Ntlanganiso Sibanda, vice-chairman AZANYU, Veli Mnguni, Steven Mzolo, Mfana Mtshali and Shadrack Rampete.

1983 and 1984

So-called reforms and many Sharpeville Commemorations in Azania

In 1983 the amended Constitution of the minority regime in South Africa initiated the so-called Tricameral Parliament in which the Coloured and Indian population groups were given a very limited political voice. Botha declared to continue ‘with maintaining Christian values and civilized standards.’ The so-called reforms of the regime turned out in practice to be a deterioration of the position of the black population.

Many resistance organizations such as National Forum (NF), Cape Action League (CAL) and United Democratic Front (UDF) campaigned against these racial elections. The NF was founded in June 1983 by 800 delegates who represented 200 organizations. The NF represented a broad opposition front comprising Black Consciousness (AZAPO/BCM), Africanism (PAC) and Unity Movement.(14) Not much later the UDF was set up in which the supporters of ANC politics were united.

Throughout the country AZAPO organized with Black Women Unite, Komitee van Tien, the Black Lawyers Association (BLA) and CUSA (Council of Unions of South Africa) Sharpeville Commemorations in 1983. By now the SASO/BPC convicts of 1977 had served their sentences on Robben Island. Three of them: Strini Moodley, Nchaupe Mokoape and Muntu Myeza spoke on behalf of AZAPO at the Sharpeville Commemorations that focused on the protest against the Tricameral Parliament and new employment laws. Ishmael Mkhabele of AZAPO: ‘Influx control laws institute one of the elements of white rule in the country. They spell loss of citizenship and extreme violence of basic human rights. Innocent people are administratively made criminals and thereby swell the prisons population.’

Patel of AZAPO spoke in reference to the racial Tricameral Parliament about the risk of ethnic organizations. On behalf of the muslim organization Qibla Ridewaan Cruyenstein spoke in response to the Tricameral Parliament plans: ‘The principle of non-collaboration prevents us from strengthening or operating the machinery of oppression.’ Muntu Myeza called upon all black people in the country to fight for their freedom in a collective effort and to overcome political differences.

In the 80s many activists of mainly AZAPO and PAC were killed by agents of the regime and members of the UDF (United Democratic Front) and ANC. Notorious was ‘necklacing’, forcing a rubber tyre, filled with petrol, around a victim’s chest and setting it on fire. People were killed for having the courage to say ‘Biko is our father’.(15)

In 1984 for the umpteenth time the Pass Laws were supposedly repealed, this time under the guise of reforms through the Ordely Movement of Black Persons law that would replace the Pass Laws. During a Sharpeville Commemoration it was observed: “The government has conceded that the pass laws are hurtful. They introduced the Bill which has been criticized for seeking to further entrench the pass laws system’.

Commemorations were organized by AZANYU, IAWUSA (Insurance and Assurance Workers’ Union of South Africa) and AZAPO. Joe Thloloe spoke on behalf of the media association MWASA: ‘Azanian masses should only be weeping after attaining their victory’.

On 16 March 1984 the Nkomati Agreement was signed. The agreement was a non-aggression pact between Samora Machel, President of Mozambique and Botha from South Africa. Speakers at various memorial services unanimously rejected this pact. The agreement did not represent the ‘oppressed and exploited masses of Azania’.

1985

Sharpeville Commemorations with killings and uprising in South Africa

In 1984 throughout South Africa the black population protested against and boycotted the opening of the racist Tricameral Parliament and the black local municipal councils appointed by the regime. When these councils wanted to raise the rent and tariffs of several municipal services such as water and electricity in Sharpeville and surroundings, a day of protest was organized on 3 September with strikes, school boycotts and demonstrations. The protesters went to the houses of the local council members asking them to join the demonstration and to give up their collaboration. When the crowd arrived at Sharpeville’s deputy mayor’s house he opened fire on the unarmed protesters. They reacted furiously and the deputy mayor had to pay for that with his life. For this murder six innocent citizens of Sharpeville were sentenced to death by the end of 1985. With the slogan Save the Sharpeville Six the Azania Komitee and Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms campaigned for their release. In another article this campaign and the plight of the Sharpeville Six will be dealt with in more detail.

In South Africa seventeen people were killed on 21 March 1985 when the police opened fire on a demonstration during Sharpeville Commemorations in Langa and Port Elizabeth. In July that year the regime would declare a state of emergency in large parts of the country.

CDA-minister Van den Broek of Foreign Affairs visited, together with other EU ministers, South Africa. Botha warned them not to visit Nelson Mandela in his prison. Afterwards Van den Broek had the nerve to declare he had wanted to point out to Mandela that violence was not helpful in finding a solution.(16)

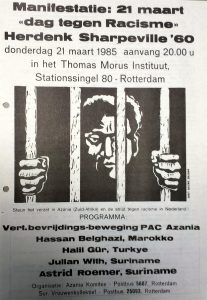

Racism in the Netherlands

Together with the Suranimese Women’s Collective (SVK) the Azania Komitee organized the Sharpeville Commemoration in March 1985. Edwin Makoti, member of PAC central leadership, spoke about the armed struggle. After the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 PAC took up arms as the first liberation movement in South Africa with their armed wing POQO, later APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Organisation). A television report of Makoti’s speech for the news was not broadcast.

Astrid Roemer and Julian With performed their poetry. The Turkish writer Halil Gur and Hassan Belghazie (Morocco) shared their experiences as (migrant)workers in the Netherlands. There were also performances of the music group of composer Hellen Gil and the choir Ondersteboven.

Also back then racism in the Netherlands was commonplace and life-threatening. The 13-year-old son of Machteld Cairo, chairman of the SVK, had shortly before been shot in the back with buckshot by a racist. In view of this the SVK, in coordination with the Azania Komitee, set up an initiative group against fascism and racism. On the well-attended first meeting also Kerwin Duinmeijer’s mother was present (Kerwin Duinmeijer, a 15-year-old boy, had been killed in 1983). Crushed by unbearable grief she said: ‘he was killed by racism… we cannot be anything but black… in all I see or experience I am reminded of him…. And nothing is of any help, no action, no protest, I am still suffering.’

1986

Violence and repression

In South Africa the Pass Laws were repealed but replaced by new legislation to the same effect. The South African regime used brutal force against the resistance of the black population in the townships. The white population washed their hands. Someone said: ‘When a black man talks with a white man about violence in the townships he receives sympathy because the whites are fully convinced that the violence in the townships is a black abnormality Botha is trying very hard to cure. This belief is even stronger now the government has effectively stopped the flow of information from the townships to the suburbs.’ At that time the regime limited and prohibited coverage of resistance in the townships.

The Sharpeville Commemorations in South Africa were frequently prohibited or those present were assaulted. In this way a Sharpeville Commemoration of AZAPO in the Cape District was prohibited. In Chesterville, Durban the police fired teargas and buckshot at the black people present. In Sharpeville AZANYU members together with the citizens cleaned the graves of the victims. In June 1987 Botha visited Sharpeville, to the horror of its citizens. He could not find the courage nor the due respect to visit the graves or to offer an apology.

In these years in the Netherlands the boycott campaign against Shell was intensified. Shell supplied oil to army and police of the Apartheid regime. In Rotterdam the Azania Komitee campaigned together with Rotterdam Tegen Apartheid (Rotterdam against Apartheid) against Shell.

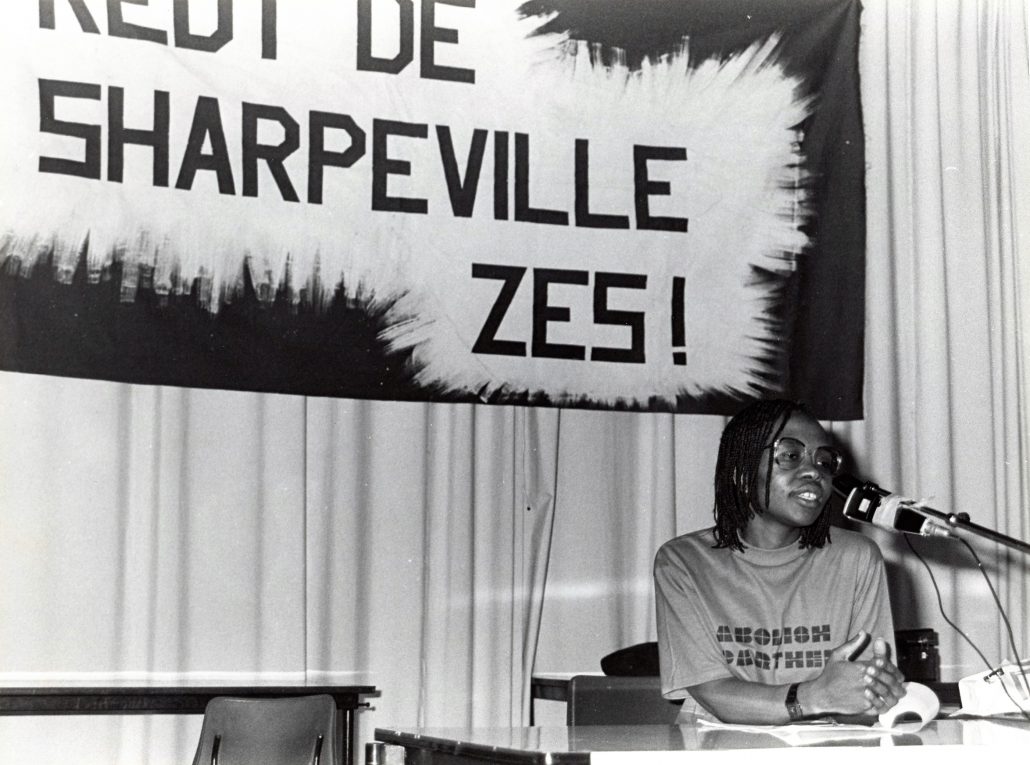

1987

In 1987 Vusumzi Nomadolo, at that time PAC representative in Europe, spoke at the Sharpeville Commemorations in Breda, Amsterdam and Rotterdam. The Azania Komitee worked closely with Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms and they set up Komitee Redt de Sharpeville Zes (Committee Save the Sharpeville Six). In Rotterdam there was close cooperation with Rotterdam Tegen Apartheid (Rotterdam against Apartheid).

Dirk Meert of the AIB (Anti Imperialistische Bond) reported on his illegal visit to Soweto and the ‘homeland’ Lebowa. He depicted the unimaginable misery, but also the unwavering spirit of resistance of the black population.

1988

Joyce Mokhesi, sister of one of the Sharpeville Six speaking in the Netherlands

Save the Sharpeville Six from the death penalty

On 18 March 1988 the execution by hanging of the Sharpeville Six was postponed at the very last minute. In July of the same year their execution was postponed again. Eventually they would all be set free in 1992. Together with Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms the Azania Komitee campaigned intensively for the support and release of the Six with the aid of the Redt de Sharpeville Zes Komitee (Save the Sharpeville Six Committee).

1989

Changes on the horizon

Resistance and oppression was also in 1989 still a reality. In order to attend the Sharpeville Commemorations thousands of people did not go to work or school, as in e.g. the Eastern Cape, Durban and Pietermaritzburg. In Port Elisabeth AZAPO, UDF and the trade unions NACTU and COSATU called for a joint commemoration.

As could be expected, the regime’s response was one of arrests, beatings and shootings. But changes were on the horizon. For the first time Botha visits Nelson Mandela in his prison. In August of that year Botha, earlier suffering a mild stroke, resigns and is succeeded by De Klerk.

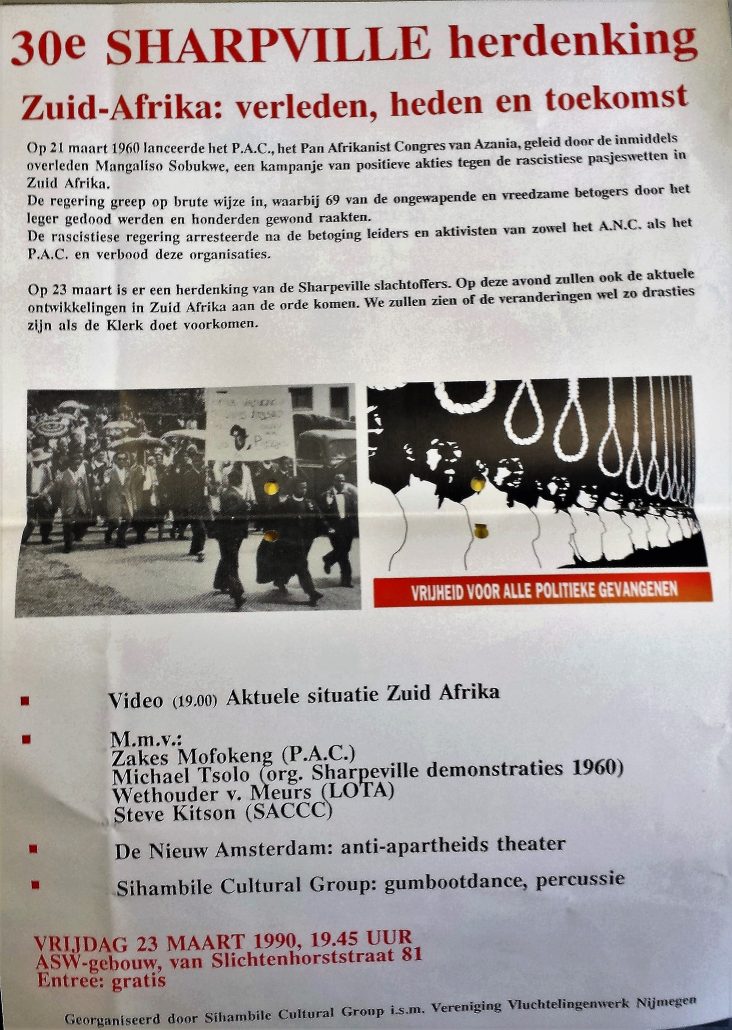

1990

Lifting the ban of liberation movements

At the opening of the parliamentary year De Klerk announces to lift the prohibition of the forbidden liberation movements and the release of political prisoners. Later that year he lifts the state of emergency. Mandela is released. PAC leader Zeph Mothopeng dies in October. The armed wing of

ANC suspends its military activities. PAC and BMCA (Black Consciousness Movement of Azania) feel this to be premature.

In 1990 white households in South Africa had more than 2.6 million weapons on a number of about 5 million white citizens. The PAC demanded the withdrawal of South African troops from the townships before a cease-fire. Another demand was to disband the notorious Koevoet and Buffalo Battalions that were responsible for the disruption of Angola, Mozambique and the underlying violence in the townships.

Meanwhile in April De Klerk made it absolutely clear in parliament that any possibility for a black majority government must be ruled out.

PAC, no longer banned, organized its congress in South Africa/Azania. PAC leaders from abroad who wished to attend the congress had to deal with severe travel restrictions and entry bans.

In Sharpeville PAC and AZAPO jointly organized the commemoration.

Constituent assembly

The Sharpeville Commemoration in the Netherlands took place in Nijmegen. The Sihambile Cultural Group and Vereniging Vluchtelingenwerk Nijmegen (Refugee Council Nijmegen) were the organizers together with the Azania Komitee. Writer, poet, musician and unionist Zakes Mofokeng and Nyakane Mike Tsolo spoke on behalf of PAC. Mofokeng lived in Switzerland after he had been forced to flee South Africa. Steve Kitson (17), political refugee (ANC) in the Netherlands, led the commemoration. The theatre company De Nieuw Amsterdam performed anti-apartheid theatre.

PAC held the view that electing a constituent assembly could only take place on the principle of one man, one vote with a common electoral list without minority rights. This constitution should only serve as a basis for the transfer of power and the preparation for new and free elections for parliament. After that the constitution had to be further agreed on.

1991

Whether or not to negotiate?

In October 1990 De Klerk was on an official visit to the Netherlands without any form of protest. The Dutch government lifted the trade embargo without consulting the liberation movements. The liberation movements considered this measure to be premature, they were not even officially at the negotiating table.

In Nijmegen that year the Sharpeville Commemoration was in the context of whether or not to negotiate with the South African regime.

Gora Ebrahim, PAC foreign office secretary, spoke at the Sharpeville Commemoration about the conditions set prior to negotiations with the regime. One of the demands was the unconditional release of political prisoners, withdrawal of the racist forces from the townships and the unconditional return of political refugees and exiles. The regime wanted to make the release of political prisoners dependent upon the negotiations and demanded from returnees statements about when and why they had fled and for what purpose they returned. Botha stated in the United Nations that Apartheid is dead. Ebrahim’s reaction was that the dead body of Apartheid was still missing …

Feminism

Buni Sexwale, chairperson of the South African Cultural Community Centre (SACCC) in Amsterdam and ANC member, spoke about the struggle of women and liberation movements. She referred to the fact that only since the 40s women were admitted to the resistance organizations and criticized the fact that women were totally absent in the negotiating fora. She emphasized that holding positions by women was not sufficient. The central question, as she put it, was if from those positions equality of women could be put on the agenda.

The other forum members were Ms De Ruiter, council member in Nijmegen for Groen Links, and Wiel Hensgens, chairperson of the platform Nijmegen Tegen Apartheid.

Once again the Sihambile Cultural Group, together with the Azania Komitee, had organized the commemoration. At the University there was a seminar on racism on the labour market on the occasion of the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

Sihambile was a mixed song and dance group led by the activist South African refugees Reuben Tshuagong and Solomon Matlanyane.

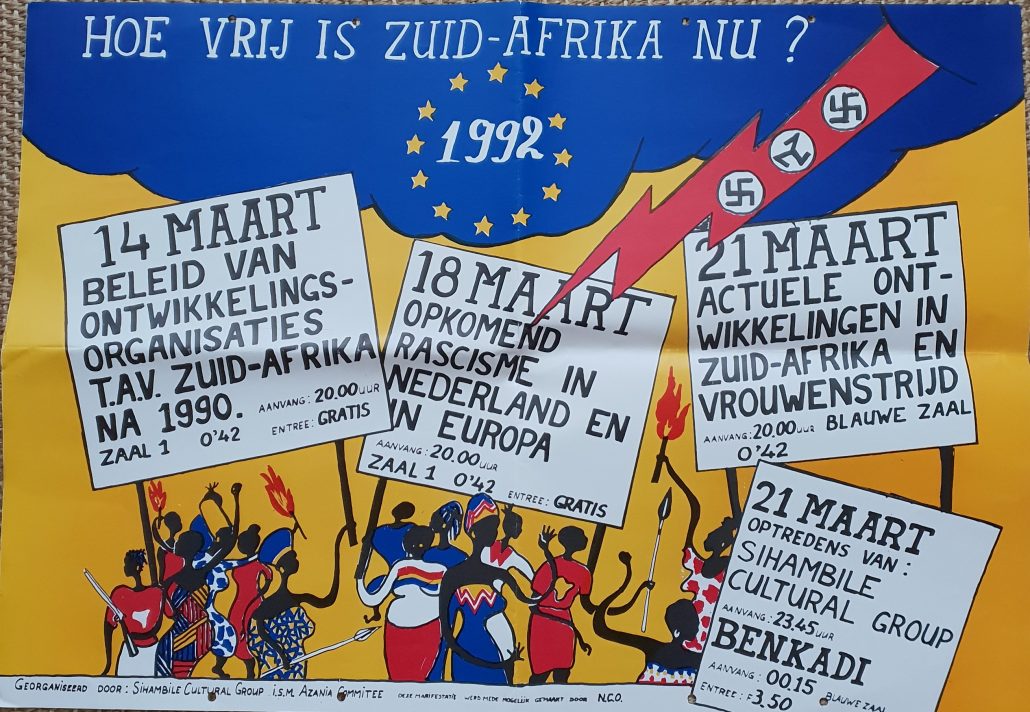

1992

How free is South Africa now?

End 1991 the CODESA (Convention for a Democratic South Africa) began negotiations that would eventually, through an interim constitution, lead to the first free elections in 1994. A month before a Patriotic Front was formed in which PAC and ANC participated. The objective was to enter negotiations with joint positions and targets. AZAPO refused to participate in the negotiations at this stage of the struggle, and PAC withdrew a bit later.

On 17 March 1992 De Klerk held a successful exclusive referendum in the white minority in order to obtain and prove acceptance of reforms and negotiations.

Unprecedented: ANC, AZAPO and PAC jointly on one platform in the Netherlands

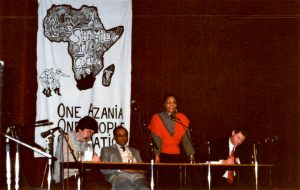

The Sharpeville Commemoration in Nijmegen om 21 March was unprecedented. Under the slogan: ‘how free is South Africa now?’ for the first time representatives from ANC, PAC and AZAPO shared the stage. Carl Niehaus, ANC representative in the Netherlands, Don Nkadimeng, secretary-general AZAPO and Selva Saman, PAC health secretary discussed the CODESA negotiations.

CODESA

AZAPO refused in principle to participate in negotiations in which a large part of the participating organizations formed an integral part of the Apartheid system. AZAPO, Don Nkadimeng, demanded a democratically elected legislative assembly. Also PAC, Selva Saman, did not see any benefits in CODESA and felt compelled to intensify the struggle in every aspect. ANC, Carl Niehaus, emphasized that participating in CODESA in not any way constituted an act of treason. According to the ANC CODESA remained the appropriate platform to negotiate a constitutional assembly as agreed on the Patriotic Front conference in 1991. Niehaus appealed to PAC and AZAPO to join the CODESA negotiations: ‘without unity of the oppressed there will be no peace, no unitary state, no hope.’ Of course AZAPO and PAC were in favour of unity of the oppressed in their country, but they continued to defend an elected constitutional assembly, negotiated on a neutral venue and chaired by a neutral chairperson.(18)

Josephine Verspaget, PvdA MP, justified the passive attitude of the Dutch government (with PvdA and CDA). She stated that this was the result of international law that stipulates that a country with a constitution cannot be forced to organize a constituent assembly. Please note, the constitution she justified had been drafted by a racist minority excluding the black majority of the population and forming the basis for the policy of Apartheid.

There were performances by the Malian music group Benkady and Sihambile Cultural Group.

Earlier that week Don Nkadimeng, AZAPO, took part in a discussion with representatives of HIVOS (de Graaf) and Derde Wereld Centrum (M. Hebink) about the one-sidedly biased material and political assistance to the ANC, virtually completely excluding other movements. Nkadimeng argued for a fund in which ANC, PAC and AZAPO ought to be represented.

The AZAPO and PAC representatives were received by the Dutch government. They made it absolutely clear that participating in CODESA was imperative because that was ‘the only show in town’ . For their part the representatives of the resistance advised PM Lubbers, Vice PM Kok and minister Van den Broek of Foreign Affairs, to cancel their planned visit to South Africa. Nevertheless, with the approval of parliament the government delegation went to South Africa. Don Nkadimeng also spoke in Rotterdam about CODESA and the white referendum.

Large anti-racism demonstrations in Amsterdam and Brussels

In Brussels Don Nkadimeng and Selva Saman joined a large anti-racism demonstration with approx. 150,000 participants. In Amsterdam 60,000 people demonstrated against racism as part of the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

After 1992 the Azania Komitee did not organize Sharpeville Commemorations anymore. In South Africa/Azania 21 March is now an annual official commemoration day known as Human Rights Day.

©Marjan Boelsma, 30 October 2018

English translation: HippoLingo

© Pictures: Azania Komitee, Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms, Jan Warner

Notes

(1) The solidarity organizations Komitee Zuidelijk Afrika (KZA), Boycot Outspan Actie (BOA) en KAIROS

(2)See part 1

(3)R.W.A. Muskens, Aan de goede kant; een geschiedenis van de Nederlandse anti – apartheidsbeweging 1960-1990 (Amsterdam, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2013) https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=25a0eedd-82bc-4f08-af77-74e3335763ba

(4)Ibid

(5) Ibid

(6)Ibid

(7)Ibid

(8)At the time the government voted in favour of the UN resolutions aimed at halting new foreign investments and imposing an oil embargo. ‘Emigration was no longer subsidized, government support for export to South Africa was stopped’ and the cultural treaty of 1951 was ‘frozen’. https://socialhistory.org/nl/collecties/nederland-tegen-apartheid-jaren-70-4

(9) A dissident ANC group.

(10) http://mayihlomenews.co.za/the-secret-bethal-treason-trial-revisited/

(12) AZANYU was organized based on the same principles as the prohibited PAC.

(13)Listen on https://www.concertzender.nl/programma/folk-it-666/

(14) Andile Mngxitama, Amanda Alexander, Nigel Gibson, Biko Lives! Contesting the Legacies of Steve Biko (New York, N.Y.PALGRAVE MACMILLAN, 2008)

(15) Ibid

(16) https://socialhistory.org/nl/collecties/nederland-tegen-apartheid-jaren-80-5

(17)Steve Kitson was ANC’s Norma and David Kitson’s son. David had been imprisoned for 20 years in Pretoria for sabotage for the armed wing of ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe, of which he was one of the leaders. Norma fled South Africa and set up, with others, the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group. This group was known for the non-stop protest in front of the South African Embassy in London and their support to all liberation movements in contrast to the ‘official’ Anti-Apartheid Movement that only supported ANC. https://nonstopagainstapartheid.wordpress.com/2012/11/16/david-kitson-a-south-african-communist-remembered/

(18) See frame with a detailed summary of Sharpeville 1992.

Other sources: Azania Vrij and Azania Presscuttings, Azania Komitee publications. To be consulted in the IISG archives, Amsterdam.

From the Azania Komitee magazine Azania Presscuttings, 1992

Sharpeville Commemoration in the Netherlands 1992

ANC, PAC AND AZAPO SHARING PLATFORM

A manifestation on 21 March with a public debate between ANC, PAC and AZAPO marked the end of a programme organised by Sihambile Cultural Group and the Azania Komitee to commemorate the Sharpeville uprising in the Netherlands.

‘How free is South Africa now?’ was the question to be answered by the speakers of the 3 main liberation movements: Don Nkadimeng, Secretary General of AZAPO, Selva Saman, National Health Secretary of PAC, and Carl Niehaus, spokesman of the ANC in the Netherlands. An audience of 120 people saw invitations going hence and forth to unite patriotic organisations by either leaving or joining CODESA (Convention for a Democratic South Africa).

The AZAPO leader recalled earlier discussions between the liberation movement, in which warnings were given for ‘the danger of the defeat if patriotic unity would not emerge in the struggle against the racist regime. AZAPO sees the internecine violence largely as being part of the regime’s divide and rule system. Though the organisations of the oppressed might ultimately share the same objectives, for the moment some do talk with the regime while others don’t…AZAPO for its part recognizes nothing patriotic or democratic in the CODESA constituency, 16 of its 19 organisations being part of the system. CODESA should be replaced by a freely elected democratic Constituant Assembly, which is actually an AZAPO demand already since the 80’s.’

The PAC leader disclosed aa CODESA plan, securing ‘white domination for the coming decade by consensus decision making and by a smart regional partitioning of the nation…The PAC conference of December 1991 had already banned CODESA because CODESA would by nature not be able to deliver free elections for a Constituant Assembly as demanded by the Patriotic Front Conference of October last year… The lack of neutral chairmanship, neutral venue and unity of patriotic forces inside CODESA had strengthened De Klerk. In addition the racist referendum of 17 march 1992 produced a strong mandate from the white constituency for the Klerk to press on with CODESA, which therefore could not be considered the universal code for the right answers. The PAC therefore sees no option but to intensify the struggle on all fronts.’

The ANC spokesman had ‘insufficient information’ to be able to confirm or deny the details of the disclosed CODESA plan, but he underlined that ‘the ANC’s participation in CODESA was by no means a sell-out. The ANC would agree with nothing short of total liberation and a united, democratic and nonracial South Africa. That has always been a guiding principle of the Freedom Charter. Under the historic conditions of the 60’s it necessitated a return to the approach of negotiating a non-racial and democratic South Africa. The ANC has shown courage to turn away from violent towards peaceful means…The ANC continues to see CODESA as a proper platform to negotiate a Constituant Assembly as demanded by the Patriotic Front Conference of October last year….Patriotic organisations like PAC and AZAPO should participate in CODESA to increase our number, which would add to the effect…Without unity of the oppressed there will be no peace, no unitary state, no hope for democracy and no redistribution of wealth for the generations to come.’

Labour MP mrs. Verspaget defended the SA position of the Dutch government (Labour (PvdA)) is the minor party in a coalition government with the Christian Democrats (CDA)). Verspaget explained the passive role of the Dutch politicians as being ‘the result of international law. No nation with a constitution could be forced to set up a Constituant Assembly….However the Dutch parliament supports the formation of an interim government…Important for the Dutch policy would be the way in which 1 man 1 vote would be implemented and a multiparty democracy would be installed… For the sake of unity and the peaceful transformation we hope the smaller organisations will also find the courage to join CODESA.’

The manifestation started with a video on the Sharpeville 1960 massacre. The group Benkadi from Mali gave a cultural performance.

Earlier that week, March 14th, a public discussion meeting had been held on development cooperation in South Africa. AZAPO leader Don Nkadimeng participated in a debate with mr. de Graaf from HIVOS (humanistic co-financing organisation/NGO) and mr. Hebink from the Third World Centre of the University of Nijmegen. Main topic was the sectarian funding of community projects connected with only one liberation movement (ANC) in the past. The AZAPO leader proposed to set up trusts in which ANC, AZAPO and PAC were all represented.

At March 17th Don Nkadimeng addressed a public meeting in Rotterdam on the white referendum and CODESA. In addition a public discussion was held in Nijmegen at March 18th on ‘The rise of racism in the Netherlands and Europe’, an issue of growing concern as would be shown by 60.000 in a broadly organised antiracist demonstration in Amsterdam three days later and by 150.000 in Brussels (Belgium) one day thereafter.

Separate meetings were also held with representatives of various political parties. Furthermore in meetings with government officials both the AZAPO leader and PAC leader were told that the Dutch government was happy with the outcome of the white referendum of March 17th. AZAPO an dPAC were asked to take part in CODESA, because it would be ‘the only show in town.’ With the blessing of the parliament and contrary to the advice by the liberation movements the Dutch government will go ahead with the planned visit to South Africa. The Prime Minister Lubbers (Christian Democrat), the Vice Prime Minister Kok (Labour Party) and Minister of Foreign Affairs van den Broek (Christian Democrat) will visit the country in august this year.

At March 23th PAC leader Selva Saman addressed a public meeting in Rotterdam on the PAC position towards CODESA and patriotic unity. Furthermore he drew attention for the Health Programme of the PAC and the work at the Chatsworth Community Health Centre in Durban. Earlier that day he had been honoured with an official reception by mr. Bram Peper, Mayor of Rotterdam, who transferred a cheque of fl. 25.000,- for the project and declared his solidarity with both leading doctors of the Centre: Comrade Dillie Naidoo (ANC) and Comrade Selva Saman (PAC).

Published in 1992