History Sharpeville (part 1)

21 March 1960 the Sharpeville massacre

21 March International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

Introduction

On Monday 21 March 1960 thousands of black South Africans took part in a PAC initiated protest agains the hated pass laws.The South African Apartheid regime responded with excessive violence and killed at least 69 people in Sharpeville. Most victims were shot in the back as they turned to flee. The shooting became worldwide known as the Sharpeville massacre. The huge resistance following the shooting caused a near total collapse of the Apartheid regime.

The resistance and the outrage in the rest of the world were the first steps in the international isolation of the Apartheid regime. The by now banned liberation movements ANC and PAC started the armed struggle. The United Nations designated March 21 International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and condemned Apartheid as a crime against humanity.

In the Netherlands the Azania Komitee took the initiative for the first in a series of Sharpeville Commemorations in solidarity with the liberation struggle in Azania/South Africa and the fight against racism in the Netherlands.

21 March 1960

Protests against the pass laws, PAC, the Sharpeville massacre, uprising in Apartheid South Africa, and effects

Pass laws

As early as in 1809 pass laws were enacted by the British for the registration of enslaved people. The pass laws remained operative after the abolition of slavery. They became an important instrument of the white minority regime to control and direct the movement of the black majority. Over the years the pass laws were extended to the extent that Africans were required to carry a book with documents and facts. These pass books (dompass) contained details about race, where you could work and live, your salary, whether you paid taxes, if you had permission to leave your place of residence, or to go out during the night, etc. In other words, the pass laws made the lives of black people a living hell. Without a pass book your life was worthless. At all times you should be able to show your pass book. If your pass book was incomplete, or you did not have it with you, you would be arrested, prosecuted and imprisoned. Those convicted were forced to perform unpaid labour on white farms where they were often abused. In the period prior to the protests in 1960 the pass laws constituted one third of the criminal sentences of Africans. Writer/journalist Bloke Modisane wrote: ‘In our curious society going to jail carried very little social stigma, it was rather a social institution, something to be expected;…more Africans go to prison than to school.’’1 Sobukwe, leader of the PAC, called the pass book ‘The distinctive badge of slavery and humiliation.’

Protests against the hated pass laws were not new. Women for example have long successfully opposed the mandatory carrying of a pass book. However, in 1956 the regime forced women to carry a pass book. That led to one of the largest protests in South African history. That year on August 9 20,000 women protested in Pretoria in front of the Union Buildings. Since 1995 August 9 has been National Women’s Day in South Africa/Azania. Eventually the pass laws were abolished in 1990.

PAC Campaign

The PAC Positive Action Campaign’2 against the pass laws emerged from the Status Campaign that defied with peaceful protests/boycotts the white supremacy of the colonial Apartheid regime and sought for independence and the return of stolen land. Liberation from slavery mentality and political awareness was a key element in PAC politics and was aimed at the (functionally) illiterate masses. Then they could choose by themselves to ‘rather die in freedom than live in abundance under slavery’’3 and rather govern themselves than under a ‘good government’ the ANC was inclined to. The founders of the PAC led by Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe left the ANC in 1959 resenting the soft ANC policy. These Africanists believed that the ANC betrayed the militant action plans of ANC Youth League adopted by the ANC in 1949. A crucial difference of opinion was the issue of land. The PAC rejected the ANC view that colonized land belonged to all who lived there. PAC wanted re-possession of stolen land for the dispossessed.

The PAC wanted to establish an Africanist socialist democracy in which anyone who was loyal to Africa was considered to be African.’4

The protest

Sobukwe announced the peaceful campaign against the pass laws for 21 March 1960. People were supposed to report at the police stations without their passes in order to be arrested and so render the system unmanageable by sheer numbers.

The announced protests were not taken seriously by the regime and the white press. The ANC did not accept PAC’s invitation to join them and issued a statement in which they distanced themselves from the campaign.

With the slogan: ‘no bail, no defense and no fine’’5the PAC leaders in the townships in the country were leading the protests to the police stations. In Soweto Robert Sobukwe took the lead. The leaders were all arrested. Sobukwe and his fellow prisoners sang in Xhosa: ‘Thina siszwe esintsundu/ Sikhalela Izwe Lethu/Elathathwa ngaba Mhlope/Mabawuyeke umhlala wethu.’ (We the black nation/Are crying for our country/ Which was stolen by the whites/They must leave our country alone.’)’6

Sharpeville massacre

The brothers Job and Nyakane Tsolo established a PAC branch in Sharpeville in 1959. Women played an active part in this PAC branch. They were badly affected by rent increases and e.g. the ban on selling home-brewn beer, one of the few sources of income for women. Consequently women protested on a regular basis against this ban and against the municipal beer halls that took away customers from their so-called illegal sale of beer and so pocketing the incomes of their men.

The then nineteen-year-old Nyakane Tsolo was Secretary and became the PAC face in the Vaal region. He had gained experience in organizing factory workers. In 1958 he led a successful strike of labourers for overtime pay at the cable plant African Cables. Tsolo took the lead in organizing the anti-pass campaign in Sharpeville. People were approached from house to house. In the meantime the police were very intimidating on the eve of the campaign and acted brutally violent and unsuccessfully hunted down the organizers.

On that sunny Monday of 21 March the black inhabitants of Sharpeville gathered in huge numbers at the local police station. Many women led the way. Nyakane Tsolo and other leaders were, as planned, standing in the front to offer themselves up for arrest. The racist police asked Tsolo to order the protesters to break up. His answer was that he was responsible for these people. The campaign could only be called off by Sobukwe.’7

After Tsolo and other leaders had been arrested the firing on the peaceful crowd began. People were stunned. They started to run the moment they realized that there was actual firing. The exact death toll in Sharpeville and at shootings in the rest of the country is not known. In Sharpeville it is believed there were at least 69 deaths, of which 40 women and 8 children and many wounded. More than 70 % of the victims were shot in the back. Wounded were later dragged out of the hospitals to be interrogated and arrested. The arrested PAC leaders were tortured by the police. After the shooting it started to rain hard and washed away the blood of the martyrs.

Sobukwe

Also among the protesters in Langa and Nyanga near Cape Town, Vanderbijlpark not far from Sharpeville and in Cato Manor near Durban many were killed and wounded on that day of protest.

The media were not permitted to be present at the funerals of the victims in Sharpeville and elsewhere. However, black journalists were there pretending to be next of kin and reported. Later the graves were desecrated multiple times by a.o. white vigilantes and the police.

The white population nearby showed no sign of compassion. On the contrary, the white population in the neighbouring residential areas prepared heavily armed for an invasion of black people from the townships. Black people who ventured into the white areas were attacked and had to fear for their lives.

40 Years later a white police officer declared without any regret: ‘We killed them not because they were black, but because they behaved like wild animals, they challenged our authority.’ Philip Frankel wrote ‘but, in the end, Sharpeville vastly superseded a simple neo-genocide in its infinitely complex institutional and human connections.’8

Revolt and crisis

After the massacre the black population responded with strikes and protests. In the Vaal area factories were shut down and trade was halted, domestic staff did not go to work. A white women from Vereeniging stated: ‘The police should kill more natives: that will get them back to work.’9

In Cape Town approximately 30,000 people led by PAC leader Philip Kgosana, 21 years old, marched towards Parliament. Never before had so many black protesters been in the white centre of Cape Town. The crowd dispersed on false pretenses. Kgosana was promised a meeting with the Minister of Justice, Erasmus, but instead he was arrested and detained for 9 months without trial. After his arrest the townships of Nyanga, Langa and Nyanga West were surrounded by the police and the army, who went from door to door with lots of violence. People were abused and arrested. Two parents on their way with their baby to the hospital were shot at. The baby was killed. It took a week to break resistance. The people in the townships under siege were too poor to have any food supplies. The white women of the anti-apartheid organization Black Sash collected food and gave that to PAC committees for distribution in the afflicted townships.

By now a state of emergency was declared. The Apartheid regime was in crisis. The South African economy was facing an enormous downturn. Foreign investors withdrew, stock prices were plummeting. The national reserves dropped to the lowest level ever. The Chamber of Commerce expressed in a memorandum that there was loss of productivity, disorder in the country, dissension in the military, loss of trust from foreign investors and loss of people due to emigration and a decline in immigration. White people assembled at the Canadian and Australian Embassies trying to obtain emigration papers. Many white people armed themselves.

Under pressure of the protests and large-scale reactions to the massacre the pass laws were suspended. That was an unprecedented victory in the history of resistance. PAC insisted on the complete abolition of the laws, demanded minimum wages and demanded the regime would negotiate with their imprisoned leaders.

The American banks intervened on behalf of the South African economy. After 17 days the pass laws were re-introduced. The regime also arrested ANC leaders and other resistance movements. The ANC and PAC were banned. Many members were arrested. Others left the country. Both movements started organizing armed resistance. The Apartheid regime became the pariah on the political international stage.

Impact in Sharpeville, South Africa and the world

‘For months public opinion was horrified by the Sharpeville massacre. In the press, on the radio and in private conversations Sharpeville has become a symbol. Because of Sharpeville men and women discussed the problem of Apartheid in South Africa’, Franz Fanon wrote in ‘The Wretched of the Earth’10

International isolation Apartheid regime

After Sharpeville Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana, India, Malaysia and Barbados took the initiative for a first boycott of South African products. President Nkrumah of Ghana appealed for comprehensive economic and political sanctions against the South African regime.

Surinam decided to stop trade with South Africa and requested the Netherlands to do the same. The Netherlands disagreed but still decided to come to an arrangement enabling Surinam to impose a trade boycott separately from the rest.11

The Dutch ambassador in South Africa was particularly concerned about the loss of potential orders for the Dutch business sector. Philips sent a letter to Forein Affairs requesting to adopt a moderate tone in response to the massacre in order to secure Dutch interests.12

Minister of Foreign Affairs, Luns, authorized, barely two months after Sharpeville, arms supplies amounting to two million dollars. The United States (US) however imposed an arms embargo on South Africa.13

The Security Council of the United Nations (UN) convened on 1 April 1960 and came to the conclusion that the events in Sharpeville could pose a threat to world peace and security. The South African regime was called on to take measures that would create ‘racial harmony’. South Africa responded by banning the ANC and PAC. For the first time in history a UN Secretary-General visited South Africa in 1961. The then Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold returned empty-handed. In 1963 a Special UN Committee Against Apartheid came into existence. In 1966 the United Nations General Assembly condemned Apartheid as a crime against humanity. The Security Council passed that resolution not until 1984. In 1966 the UN designated March 21 International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

The PAC lobbied successfully, with the support of the Organization for African Unity (OAU) 14

, for an official observer status for the ANC and PAC as legal liberation movements at the United Nations. In 1974 South African membership of the UN General Assembly was suspended. In 1975 the OAU officially adopted a PAC policy paper in which the illegal status of South Africa was substantiated.

In 1970 Afro-American workers demanded from the Polaroid company in Boston to stop supply of products tot he South African regime. They had found out that these products were used for enhancing effectiveness of taking pictures for the hated pass books. Polaroid was the only company for South Africa that supplied equipment with which photos for the hated pass books could be produced very quickly. The protesters handed out flyers saying: ‘Polaroid imprisons people in 10 seconds.’ In 1977 Polaroid stopped all deliveries to South Africa.15

Sharpeville after the massacre

The survivors suffered from post-traumatic stress disorders for decades due to the dramatic events in Sharpville. The constant awareness of threat, the nightmares and rage against those who collaborated with the Apartheid state took their toll. The mass-arrests, the deaths, the wounded deprived families from their providers. Many wounded remained disabled and became dependent on the care of their poor families.

Till 21 March 1960 Sharpeville was known as a centre with stars in sports and music. After that date many left the community looking for better places. Not far from Sharpeville the white perpetrators and supporters of the massacre and their offspring still live their unimpeded and peaceful luxurious lives.

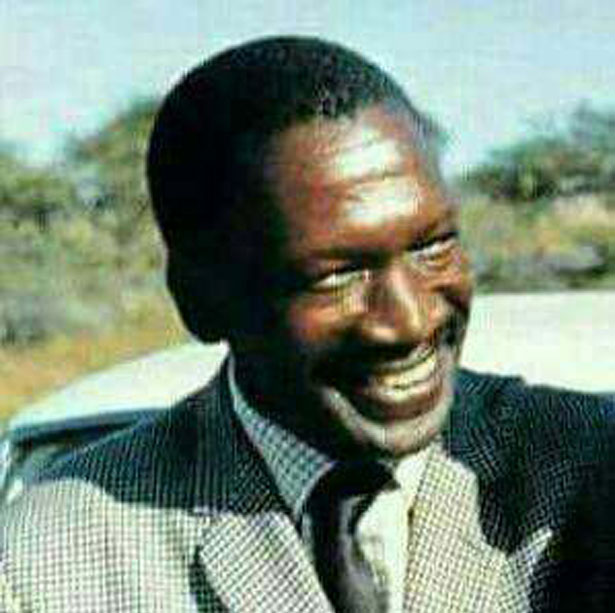

Nyakane Tsolo was released on bail in 1961 and fled to Lesotho. After that he took a military training in Egypt for the armed wing of PAC. He stayed in East Germany from 1963 to 1973. In secret he then fled with his family to the Netherlands and made a new home in Rotterdam. He was the PAC representative in the Benelux and worked closely together with the Azania Komitee. In 2001 he returned to Azania and died there a year later. Nyakane Tsolo is buried in Sharpeville.

Sharpeville Commemorations in the Netherlands

Soon after the Sharpeville massacre about 500 people took to the streets and led by the Labour Party about 1,000 people assembled in the Stock Market. In The Hague about 1,000 people went out to protest. One of the speakers was Otto Sterman, a Surinam actor, who equated the fight against Apartheid with the fight against nazis. On 31 March the Federation of Surinam Organizations organized a protest in Amsterdam. ‘Every hour the government remains silent about this issue is an insult to the Surinam and Antillean people’, according to federation chair F. Moll.16

In the years after the anti-apartheid groups paid little or no attention to Sharpeville. The policy of most anti-apartheid movements was to promote the ANC as the only serious liberation movement in South Africa. If Sharpeville was mentioned at all, then it was invariably linked to the ANC. The impression was conveyed that the ANC had played a decisive role in the anti-pass laws campaign, and sometimes that role was just bluntly claimed. They refused to give a voice to PAC in the Netherlands.

protest Sharpeville, 1960

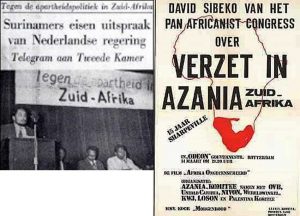

In 1975 the Azania Komitee took the initiative for the first in a series of Sharpeville Commemorations in solidarity with the liberation struggle in Azania/South Africa and the fight against racism in the Netherlands. David Maphumzana Sibeko, PAC representative at the UN, spoke in Haarlem, Groningen, Eindhoven and Rotterdam about resistance in Azania/South Africa. He introduced us to Nyakane Tsolo, who lived as a political refugee in Rotterdam with his family.

In Haarlem BOA (Boycott Outspan Action) joined the Azania Komitee. At that moment BOA was campaigning against emigration to South Africa. Their joining us was remarkable because they and other anti-apartheid organizations unilaterally supported the ANC and opposed PAC.

In Rotterdam the Sharpeville Commemoration was supported by a wide variety of organizations such as: LOSON (National Organization for Surinam People in the Netherlands), Unidad Caribia, KWJ (Critical Young Workers), Palestina Komitee, NIVON and Wereldwinkel (Oxfam shop). The workers’ choir Morgenrood (Aurora) performed.

At the commemoration the film Last Grave at Dimbaza was shown. This award-winning documentary, produced by Nana Mahomo, was clandestinely shot in South Africa in 1974. Mahomo, co-founder of PAC and secretary for culture, had left South Africa with 2 others at the request of his organization in order to set up foreign missions.

The film made a deep impression on those present. The film ends showing a graveyard for black children in Dimbaza where new graves have already been dug for the children to die next due to the high mortality rate. The film ends as follows:

‘During the hour you’ve been watching this film, six black families have been thrown out of their homes, sixty blacks have been arrested under the pass laws, and sixty black children have died of the effects of malnutrition. And during the same hour, the gold mining companies have made a profit of £35,000.’17

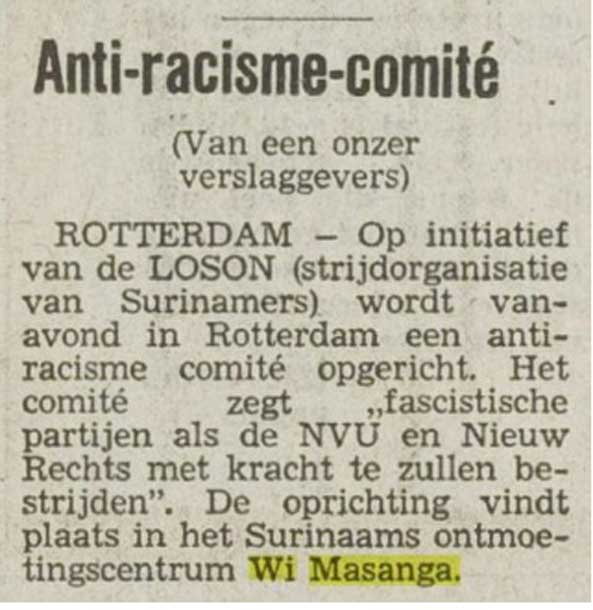

Representing LOSON Ronald de Waal spoke about racial discrimination and the imperative for solidarity. He criticized the proposed racist re-allocation of specific population groups in Rotterdam. In that year LOSON launched a national anti-racism campaign together with anti-racist committees in Utrecht, The Hague, Tilburg, Amsterdam and Rotterdam. The Azania Komitee joined them. The campaign also targeted the policy of the Minister of Justice, Van Agt, who protected fascist organizations such as Nieuw Rechts (Neo Right) and the NVU (Dutch People’s-Union). The election propaganda of these parties was packed with racist slogans in a permanent smear campaign ‘against Surinam and Antillean people and other foreigners.’ The leader of Nieuw Rechts, Max Lewin, recruited mercenaries in the Netherlands for the white minority regime of Ian Smith in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). LOSON and the members of the anti-racism committees demanded a ban on Nieuw Rechts and the NVU, complying with the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.18

To be continued with part 2: https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/10/30/history-sharpeville-part-2/

The second part of History Sharpeville continues with a survey of Sharpeville Commemorations in the Netherlands with an account of the events in South Africa/Azania and the commemorations there. The first Sharpeville Commemoration (1975) by the Azania Komitee is described in part 1.

©Marjan Boelsma, 14 May 2018

English translation: HippoLingo

Het Vrije Volk, 21 march 1975.

Tribute

Mike NyakaneTsolo

Tribute to Mike NyakaneTsolo (1939-2002) dear friend and comrade

The first time I met Gladys and Mike was in Rotterdam March 1975. They were introduced by David Maphumzana Sibeko, PAC representative at the UN. He was the keynote speaker at the first Sharpeville Commemoration organised by the Azania Komitee.

It was the start of a close working relationship in all kind of activities in support of the liberation of Azania and of a growing close relationship. I remember from those early years the many times I came in the evening to visit Mike and Gladys to learn and discuss politics and drinking white wine mixed with sweet fruit.

Mike told us the true story about the brave people of Sharpeville who ‘challenged what was never ever challenged in putting the struggle of the dispossessed on the international agenda.’

Mike was teaching us, young men and young women in Europe who wanted to change the world, on Azanian politics, PAC politics and international politics. And about the ultimate aims of Pan Africanism and socialism in an Africanist democratic way. With unity, nonracialism and international solidarity as leading principles. He was very important amongst those who made us hear the crying voices from occupied Azania.

For the Azania Komtee is was a great honour and opportunity to work with Mike. In March we organised almost every year Sharpeville Commemorations and after 1976 Soweto Commemorations in June. The commemorations became a platform fort he liberation movements of Azania and expressions of solidarity.

Amongst the many activities there were boycotcampaigns, economic, cultural and political. We had campaigns for the relaese of political prisoners, we had demonstrations, picketlines and many meetings. Mike was also fighting sectarism by the anti apartheidmovements in Europe. He started an organisation to unite all South Africans in Exile in the Netherlands. He took a stand against paternalism and the professional activists in so-called socialism and so called solidarity. He and his family experienced both of it. During the years of exile in East Germany and on their flight from there tot he Netherlands. It endangered their lives.

Sharpeville became again worldnews in 1985 with the case of the Sharpeville Six. Mike worked with us to save the lives of the Six.

And there were too many commemorations of comrades and common friends who died far away in Azania and nearby in the Netherlands. I remember Robert Sobukwe, Nyathi Pokela, Jafta Masemola, Zeph Mothopeng, Ad van Praag from Cineclub in Amsterdam, Phillip Mokgadi in Germany, Steve Kitson in Amsterdam and my late husband Jos Derks.

Nyakane was a refugee, an exile in Rotterdam. Over the years he became a Rotterdammer with a clear stand. In 1990 he spoke at the inauguration of the Steve Biko square. I quote: Rotterdam will be honoured with the Steve Biko square. Still there is the fact that a lot of streets are named after our oppressors. I keep hoping that will change one day.’ He also supported the cooperation and exchange between the people of Rotterdam and Twin city Durban during the nineties.

Traumatic memories and the stress of being in exile are important factors to cause illness and death. The wounds of Sharpeville, Mike wounds were never healed. In the film Viva Azania, Boycot South Africa we made in 1976 he expressed what he felt on that day the 21 of march in Sharpeville. Being held in the policestation separated from his people he heard the shooting, believing it was teargas. Then after realising that the racist police was shooting at the peaceful demonstrating people: ‘Oh god, now I am broken.’

Still he kept on serving, suffering and sacrificing for the struggle. He kept on fighting for Azania in all possible ways. ‘Freedom in our lifetime.’ He reached freedom. It did however not completely meet his ultimate goals. He said: I had a dompass and now I have a South African pass. We have a new flag and we can sing our national anthem. And we are free to beg abroad for money to buy our land back that was stolen.’

This is an edited version of my speech at his funeral 2002,12 juli in Sharpeville.

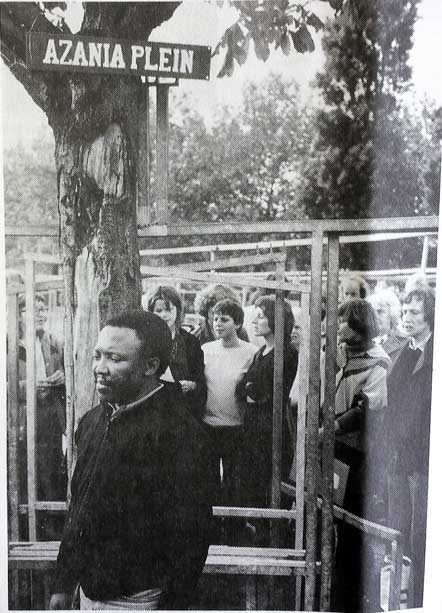

Changing Afrikaanderplein to Azaniaplein in Rotterdam June 1978, with Nyakane Tsolo

Notes

1, http://abahlali.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Fanon.pdf

2, Dit was mede geïnspireerd op de Positieve Actie Campagne onder leiding van Kwame Nkruma en die in 1957 tot de onafhankelijkheid van Ghana leidde.

3, Speeches of Mangaliso Sobukwe from1949 – 1959 and documents of the Pan Africanist Congress Azania , PAC Observer Mission to the UN, New York.

4, Speeches of Mangaliso Sobukwe from1949 – 1959 and documents of the Pan Africanist Congress Azania , PAC Observer Mission to the UN, New York.

5, De Freedom Riders in de VS waren geïnspireerd door de vreedzame PAC acties tegen de Passenwetten en gebruikten ook de leuze: no bail, no defense, no fine. Stokely Carmichael met Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution, the life and struggles of Stokely Carmichael (New York: Scribner,2005)

6, Benjamin Pogrund, How Can Man Better Die: The Life of Robert Sobukwe (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 1990)

7,Philip Frankel, An Ordinary Atrocity: Sharpeville and Its Massacre (Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, 2001) en interview met Nyakane Tsolo in de korte documentaire Viva Azania, Boycot Zuid-Afrika! Door Cineclub en Azania Komitee, 1977.

8,Philip Frankel, An Ordinary Atrocity: Sharpeville and Its Massacre (Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, 2001)

9,Philip Frankel, An Ordinary Atrocity: Sharpeville and Its Massacre (Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, 2001)

10, Frantz Fanon, De verworpenen der aarde (Utrecht/Antwerpen A.W. Bruna & Zoon, 1971)

11,R.W.A. Muskens, Aan de goede kant; een geschiedenis van de Nederlandse anti-apartheidsbeweging 1960-1990 (Amsterdam, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2013) https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=25a0eedd-82bc-4f08-af77-74e3335763ba

12, Ibid.

13, Ibid.

14, Sinds 2002 African Union (AU).

15, http://africanactivist.msu.edu/organization.php?name=Polaroid+Revolutionary+Workers+Movement

16, R.W.A. Muskens, Aan de goede kant; een geschiedenis van de Nederlandse anti-apartheidsbeweging 1960-1990 (Amsterdam, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2013) https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=25a0eedd-82bc-4f08-af77-74e3335763ba

17, http://southafrica.qc.cuny.edu/last-grave-at-dimbaza/

18,Internationale Verdrag inzake de uitbanning van alle vormen van rassendiscriminatie, New York, 07-03-1966. Geldend van 09-01-1972 t/m heden. http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBV0002911/1972-01-09