Background and repercussions of biased white solidarity

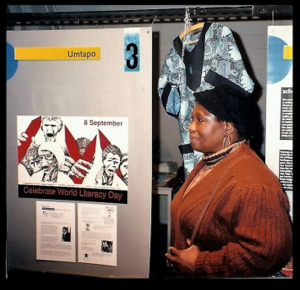

Film footage (Cineclub) demonstration Shell boycott in Rotterdam, 1986. With singer James Madhlope Phillips (1919-1987) from the ANC.

In this fragment the topics I would like to discuss converge: racism in our own country, the Anti-Apartheid movements and their perspective on the liberation struggle in South Africa/Azania and its repercussions. The central theme in my story is white.

The beam in our own eye

The Shell demonstration

The Shell demonstration was also joined by the action committee of mostly Cape Verdean seamen, who opposed their being made redundant. In 1983 the shipping company of Nedloyd made redundant 220 Spanish, Portugueses and Cape Verdean seamen on the basis of unreasonable grounds. All this took place in a united effort of the shipping company, the Dutch State and the Union of Seamen of the Federation of Dutch Trade Unions in order to secure the jobs of Dutch seamen. How many people in this demonstration would have been aware of this racism in their own country? After all, a progressive country which opposed Apartheid could not be racist……

White miners against employing black schooled workers. South-Africa 1979

For the black political refugees over here this was nothing new. In 1922 the back then white-dominated SACP supported a strike of white miners with the slogan ‘Workers of the world, unite and fight for a white South Africa!’. And that was not for the first and last time.

The observations and experiences in the Netherlands of black South African exiles disrupted the patronising complacency of the Dutch Anti-Apartheid organizations. They were very irritated about that, but more on that later.

Different views

Everyone supported the oil boycott: all Anti-Apartheid organizations, left-wing parties, trade unions etc. united in their demand for an oil boycott. But disagreement about and support to the liberation movements in South Africa/Azania was considerable.

Apartheid

English and Dutch colonialism is specifically responsible for the legacy South Africa/Azania has to face now. Apartheid was already introduced by the English. Rhodes: ‘we are to be lords over them.’ Apartheid President Verwoerd (of Dutch origin) is clear: we want to keep South Africa white and that means white dominance. The Dutch theologian and politician Kuyper inspired politics of Apartheid with his beliefs that groups should lead separate lives. The convictions from Verwoerd and Kuyper can still be traced back in the Netherlands. Just think of the current painful discussion on race.

Some historians claim that Kuyper’s ideas represented the essence of Apartheid. The text in the slide is on display in the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. White people in South Africa called themselves Europeans because in their opinion Europe was civilized.

Azania Komitee

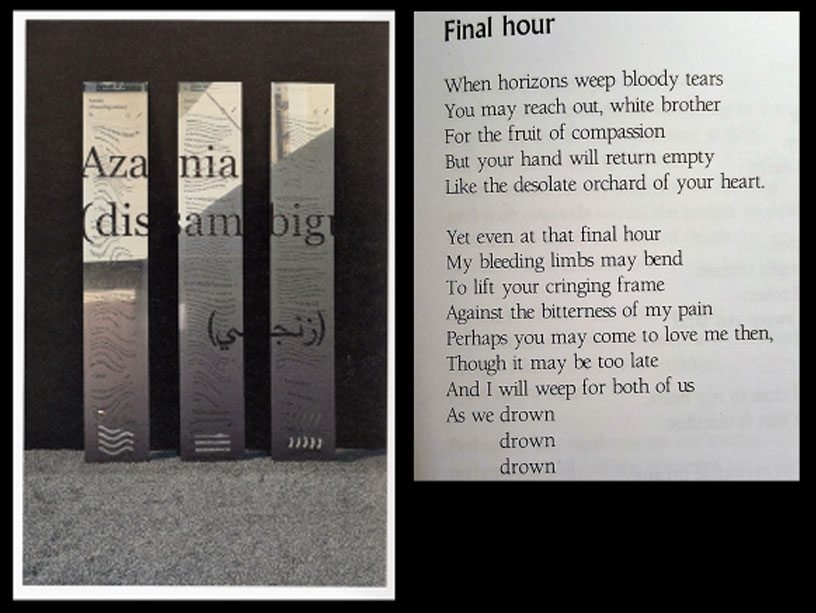

Together with other volunteers I set up the Azania Komitee in 1974. Our objective was to support the liberation movements in South Africa/Azania in their struggle against the colonial Apartheid regime, which went beyond Anti-Apartheid. The name Azania was and is for many people and movements in South Africa the name of liberation for South Africa. The name Azania was avoided by the established Anti-Apartheid organizations.

On the eve of negotiations in the early nineties the regime stated that a new name was non-negotiable. A government minister said that many black people want South Africa to be renamed Azania. He was alluding to ‘the extreme Pan Africanist Congress.’ He added that the name sounded as a warning for a break in history. He said: ‘We believe a complete break with the past is inconceivable .’ And see how successful they have been now.

Why the Azania Komitee

We were inspired by a.o. Amilcar Cabral, leader of the PAIGC in Guinea Bissau, who said: ‘do not hide anything from the masses of the people. Do not tell lies. Expose lies and do not promise easy victories.’ We studied books by Kwame Nkrumah e.g.‘The Challenge of the Congo, a case study of foreign pressures in an independent state’ and ‘Neo colonialism, the last stage of imperialism’. This book addresses financial enslavement related to formal political independence. This is something we also saw taking place in South Africa. We read about Pan-Africanism and Walter Rodney’s ‘How Europe underdeveloped Africa’. Slowly but gradually it dawned upon us how the system worked.…

Setting up the Azania Komitee originated in the fact that in the Netherlands Anti-Apartheid Movements AABN (Anti-Apartheid Movement Netherlands), BOA (Boycott Outspan Action) and KZA (Committee South Africa) exclusively supported and informed about the ANC (African National Congress). Other resistance organizations, including their campaigns and political prisoners, were barely mentioned, trivialised and inadequately represented. E.g. Mangaliso Sobukwe, leader of the PAC (Pan Africanist Congress), for whom legislation was initiated to silence him for the rest of his life. Or Jafta Masemola, the longest-serving Robben Island prisoner or the roughly 100 PAC political prisoners who were hanged in the early sixties. Pan-Africanism and Black Consciousness were framed as anti-white, narrow-mindedly nationalistic and anti-left. The initiators wanted to correct that unjust situation. It was considered to be a neo-colonial attitude from the West to establish which was the ‘best’ movement. Or as a refugee remarked: ‘it is not a political beauty contest.’

For the Azania Komitee the struggle and sacrifices of the black South Africans/Azanians were their point of focus. They were crucial. Solidarity movements could only exist through the struggle and the pain there and had to establish a cause and effect relationship with racism, colonial past and neo-colonial present here.

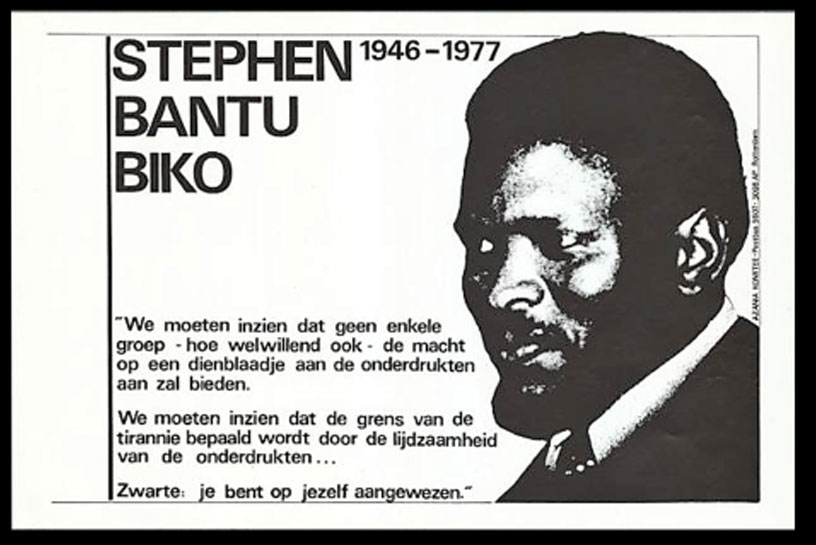

The white-dominated Anti-Apartheid movements initially accused Steve Biko, leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, of reverse racism and serving Western imperialism. After his death he was claimed by them for the ANC. At the same time they did not put their energies into fighting racism in their own country and did not establish the link between Apartheid South Africa and the cruel Dutch colonial history. They opted for restraint and that meant no platform, no support for the radical liberation movements such as the PAC and BCM (Black Consciousness Movement). The ANC was presented as a sensible option. The repossession of stolen land, decolonization disappeared in the illusion of Anti-Apartheid.

A gruesome confrontation

The Jan van Riebeeckhuis in Culemborg

The refugee South Africans in the Netherlands arrived in a country that denied racism, was ignorant and chose to remain ignorant about white supremacy, its origin and that reacted in a defensively offended manner when reminded of that. They arrived in a country that portrayed Jan van Riebeeck as a man who contributed to the development of South Africa and who loved gardening; a country that shamelessly obscured the violent land grab, slavery, the genocide; a country that names streets after white Boer generals, racist colonizers. That was a gruesome confrontation.

There were protests in several places to put those street names drenched in blood on the agenda. In 1978, during the commemoration of the Soweto Uprising of 1976, the Rotterdam Afrikaanderplein was symbolically renamed Azaniaplein with the help of political refugee Nyakane Tsolo. There was a strong appeal to substitute the names of the white oppressors for black freedom fighters. Finally, in 1990, Rotterdam had a Steve Bikoplaats and a Lilian Ngoyiweg. Lilian Ngoyi was a prominent ANC leader. In the presence of representatives of the ANC, PAC and BCM the street names were unveiled. Nyakane Tsolo, in 1960 leader of the anti-pass campaign in Sharpeville, commented: ‘what remains is a district (Afrikaanderwijk) in Rotterdam where many streets are named after our oppressors. I keep hoping that will change one day.’ Nearly 30 years later these names and the names of other colonial criminals are still there, but the debate has been reopened by a new generation of black activists and activists of colour. Berlin recently decided to rename colonial street names in the near future. .

Criticism from black South African refugees

Dr. Oshadi Mangena from the BCM, political refugee in the Netherlands, was very outspoken. I quote: ‘The Dutch need to understand that the root of Apartheid is in colonialism; land has been stolen from us blacks. Solidarity groups need to educate themselves in the history of Apartheid. In the Netherlands we are subjected to the same conditions as in South Africa. Solidarity groups do not realize that South Africa is in the Netherlands too. E.g. a black woman works as a nurse but was ignored by the patient’s family for they were looking for a real white nurse. In shops black women are frequently watched because the assumption is they are going to steal. Discrimination is so omnipresent you do not even notice it anymore. People show sympathy from a sense of superiority and colonialism. Solidarity groups ask which party you belong to. But in South Africa as a black person, whether you are organized or not, you are involved in the struggle, whether you want to or not. We are forced by solidarity groups to make political choices, which create division rather than unity. We have seen how South Africans in the Netherlands were not given the opportunity to meet fellow South Africans. They were told: ‘we have paid for the tickets.’ And finally: ‘do not see us as your hobby, for us it is a question of life and death.’ This is in sharp contrast to what the white South African Antjie Krog points out in the Tell Freedom exhibition guide ‘that during Apartheid white Afrikaners learned from the Dutch not to discriminate’…

At that time international conferences against Apartheid were booming. Also on that stage western white (subsidized) Anti-Apartheid groups were dominant. Black solidarity groups were mostly not represented. They had fewer financial means. White people took the spotlight, presented themselves as the experts. They turned into sacrosanct institutes that complacently congratulated each other at those conferences and tolerated no contradiction. Representatives from the Azania Komitee have witnessed that both internationally and at home. They did not want us to draw attention to PAC political prisoners sentenced to life, the brutal repression AZAPO members had to deal with, etc.

The established Anti-Apartheid groups had a major influence on the press, political parties, relief organizations, cultural organizations, etc. They dictated who should or should not be heard and supported.

Biased solidarity

Also churches found it hard to abandon their white positions. They were severely criticized by the black community: ‘We are sick and tired of those white Messiahs who martyr themselves abroad by talking about the suffering of the black people.’ The criticism fell on deaf ears. KAIROS, a church-based Anti-Apartheid group, opted for the ANC because the ANC offered more of a perspective on the future and the PAC was too exclusively black……

Why did not a single paper have a black correspondent in Azania? Was it because white journalists would report more objectively? The Ghanaian journalist Cameron Duodu concluded in 1986 that virtually the entire white press is racist. And how come that still today we do not have black journalists??? Still that whiteness.‘Whiteness in one of its most vicious forms: propped up as authority, sold as neutrality’, as Simone Zeefuik characterized it in her contribution to the Tell Freedom exhibition guide.

An example of the bitter impact of biased solidarity. Hamilton Keke, PAC,

ex-Robben Island prisoner tells his story:

‘The newspaper The Guardian did not want to publish any of my press releases as a PAC representative. They repeatedly informed me that they would only publish information about South Africa supplied by the Anti-Apartheid movement and other organizations run by white people.’ Outraged Keke pointed out that no single white man/woman‘had lived in the ghettos of racist South Africa and that not a single white person is aware of the sentiments and the aspirations of the African population.’

In 1987 the Anti-Apartheid movement organized the CASA-conference Culture in an other South Africa. Pluralist standards applied for Dutch politics in the invitation policy. All parties including the VVD (Dutch People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) were invited. This did not extend to South African resistance. Only the ANC and related organizations were invited. In a letter to the organization the Azania Komitee deplored this procedure. In her reply writer Mies Bouhuys, chair of the advisory committee, emphasised that the ANC was open ‘to black and white.’ As if valuing black leadership presupposes an anti-white attitude. White people were not criticized because of their skin colour, but because they were the oppressors. The largest black media union, MWASA, was said to be dominated by black nationalist politics. According to these know-it-alls that meant: South Africa for the blacks and the whites into the ocean. Fear of the black menace and white genocide. A drum that many white people in today’s South Africa still beat every day.

Minister Van Dijk, de schrijvers W.F. Hermans en Gerard Reve

In 1982 it could happen in the Netherlands to have a minister for Development Cooperation (Van Dijk) who had published a series of pro-apartheid articles. Despite the protests he remained in office after a poor excuse. Black South African refugees insisted that at least he would outline his evolution from racist to anti-racist and they started a petition. I think you can guess: the petition was not successful.

The well-known authors WF Hermans and Gerard Reve visited South Africa in spite of a worldwide cultural boycott. Hermans stated on South African television that if black people in South Africa were to have governmental responsibility this would mean the end of the country. He also believed Moluccans should be separated and was against ‘miscegenation’. Reve stated to be pro-Apartheid and felt that Apartheid was not based on racism but on Christian ethics.

The poet Julian With wrote: ‘there was a time I thought it highly unlikely that white people who were members of the VARA and the VPRO (two progressive public broadcasting associations) could be racists. The same for people who voted for the PvdA (Labour Party) and other small left-wing parties. From all of these little straws that are essential if you do not want to pass the entire population for racists, I have been robbed in recent years. Who offers me new ones?’ ’.

Biased solidarity

Here you see a remarkable example of paternalism from the Komitee Zuidelijk Afrika who reprimands South African refugees who were highlighting their organizations to the churches.

In 1986 Cineclub and the Azania Komitee started an international action to save the Sharpeville Six who were sentenced to death. One of them was the first woman on death row, Theresa Ramashamola. The other committees did not want to get involved because the Six were not members of the ANC. We ran our campaign in close contact with the families of the Six. The Six were saved from the gallows as the result of international actions and action in South Africa itself. And also SAWO, a Surinamese Labour Organization, successor to LOSON (National Organization of Surinamese in the Netherlands) was involved in the action.

International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Sharpeville, racism in our own country

In 1975 the Azania Komitee took the initiative for the first in a series of Sharpeville Commemorations in solidarity with the liberation struggle in Azania/South Africa and the fight against racism in the Netherlands. David Maphumzana Sibeko, PAC representative at the UN, spoke in several places about the resistance in Azania/South Africa. Ronald de Waal spoke in Rotterdam on behalf of LOSON about racial discrimination in the Netherlands and the imperative for international solidarity.He criticized the proposed racist re-allocation of specific population groups in Rotterdam, an omen for today’s Rotterdamwet if you will. In that year LOSON launched a national anti-racism campaign together with anti-racist committees in Utrecht, The Hague, Tilburg, Amsterdam and Rotterdam. The Azania Komitee joined them.

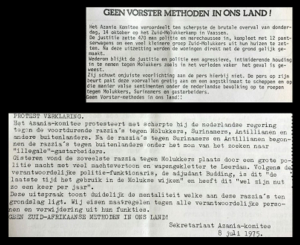

The campaign also targeted the policy of the Minister of Justice, Van Agt, who protected fascist organizations such as Nieuw Rechts (New Right: a Dutch right-wing nationalist party) and the NVU (Dutch People’s Union: Neo-Nazi political party). The election propaganda of these parties was packed with racist slogans in a permanent smear campaign ‘against Surinamese and Antillean people and other foreigners.’ Sounds familiar these days…

The annual Sharpeville Commemorations and after 1976 also the Soweto Commemorations provided a platform for representatives of the liberation movements and the anti-racism struggle in the Netherlands. Denise Jannah, now an internationally acclaimed jazz singer, and Ida Does, later award-winning documentary maker, performed with the LOSON choir in 1980. In 1985 Astrid Roemer, recent PC Hooft Award winner (a very prestigious Dutch literary lifetime achievement award), attended the Commemoration.

In 1991 the Vereniging Ons Suriname (Our Surinam Association) welcomed two ex-Robben Island prisoners: Strini Moodley, one of the leaders of the BCM and Khotso Seatlholo, one of the leaders of the Soweto Uprising in 1976. They addressed their audience at several Soweto Commemorations in the Netherlands.

In 1992 representatives of the ANC, PAC and AZAPO (Azanian People’s Organisation) shared one stage. A unique situation.

Eurocentric narrative

For generations Dutch education has failed in teaching accurate knowledge of racism, racial oppression and the slave trade by the Netherlands, the resistance and the present repercussions. We live with a Eurocentric narrative which portrays Africa as a poor, primitive and violent continent and which ignores the fact that the Netherlands has a historical responsibility for the underdevelopment of Africa. Dutch aid is essential for Africa because Africa cannot do it on its own. That is directly related to the denial of present-day racism. As Professor Gloria Wekker reminds us that hundreds of years of colonialism and slavery have their repercussions in our present. Jessica de Abreu states in her contribution to the Tell Freedom exhibition guide: ‘Due to the dominance of Eurocentric ideas, we have ignored for example how Apartheid in South Africa and racism in the Netherlands are historically connected.’

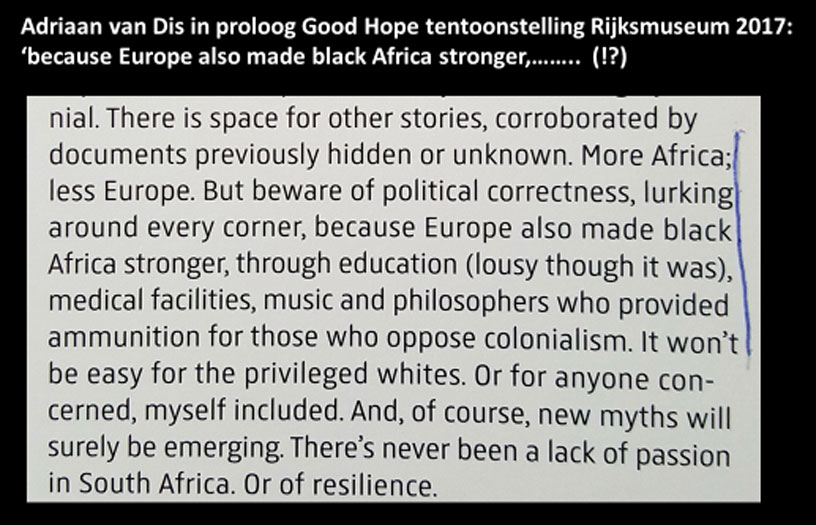

A good example was the recent exhibition Goede Hoop in the Rijksmuseum about the relationship between South Africa and the Netherlands. South African and critical Dutch visitors wrote in an open letter that the exhibition did not acknowledge the fact that ‘colonization is both a historical crime and a violent process whose impact is still felt today’ and it did not provide ‘a clear representation of the role the Netherlands played in the systematic oppression and exploitation of the people in South Africa.’

If it is up to modern education the Dutch will never hear and see the bitter truth. Associate Professor of Sociology Melissa Weiner looked into our history teaching. She outlines how in primary school texts are presented written from a Eurocentric perspective and emphasizes Western superiority. That is how colonial thinking, culture and history remain intact. In that narrative the voice of the oppressed is trivialized, not even mentioned. Textbooks reveal in particular our (white) unique political, economic and cultural role in the world. A model for other countries. Textbooks emphasize the non-existence of technology, illiteracy and poor healthcare in Africa. In a word ‘primitive’. So there was an urgent need for the West to intervene and ‘to do good.’ The textbooks do not point out the violent conquest and slavery in our past and the neo-colonial exploitation these days. After all we brought and bring civilization. And the pre-colonial history is non-existent. In the textbooks slavery in the Golden Age is disconnected from today’s inequality in the world.

Adriaan van Dis in proloog Good Hope, Rijksmuseum 2017

The Eurocentric narrative does not take any responsibility for the present implications of centuries of racial oppression and exploitation. The texts normalize European civilization. Not a single word about Pan-Africanism and national liberation movements against colonialism. The struggle for independence is not perceived as anti-colonial resistance but rather as brutal outbursts of violence from ‘wild and fanatic tribes’ with white people as the victims. In this way Africans are being robbed from their humanity. Melissa Weiner found in 40% of the books illustrations of half-naked and poor Africans, starving and dying children. It is ‘poverty porn’. It is material with which relief organizations such as NOVIB/Oxfam generate revenues and with which the press tries to be successful. It encourages white volunteers to do ‘good works’ in distant places. And at the same time turn a blind eye to the homeless asylum seekers, the undocumented people round the corner and not correlate its causes with the price they pay for your privileged life. It prompts a white Albert Heyn project manager on Curaçao to abuse the ‘I have a dream’ speech by dr. Martin Luther King for her dream in front of the black employees: starting a Albert Heyn franchise. It makes white solidarity organizations brush aside radical liberation movements as barbaric. And be outraged by the slogan ‘one settler, one bullet’ and forget that in WWII we said that the only good German was a dead German…

South Africa/Azania today

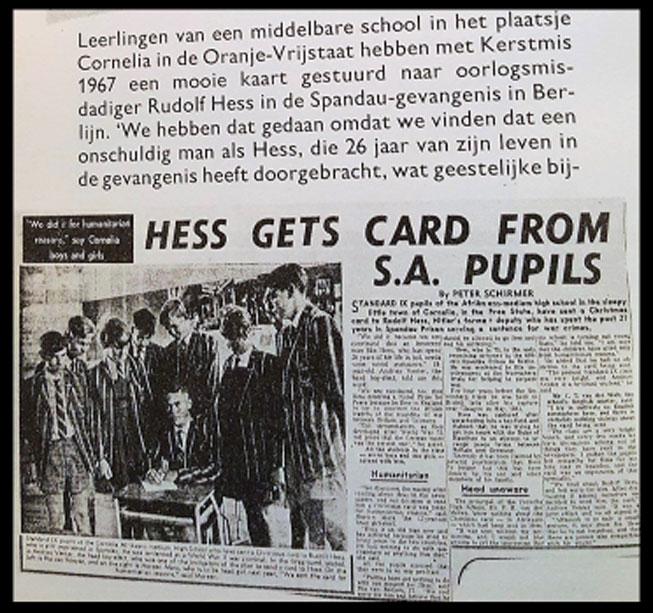

Apartheid has been abolished; the liberation struggle has not been completed. The white minority still has not had to pay the price for their centuries of violent occupation, exploitation and racism. Capital, resources and the stolen land are mostly in their possession. The much applauded transfer did have a price for the black majority. Not another word about reparations, land reform, nationalizations etc., but instead further privatization and complying with the requirements of the IMF. But what can you expect from a white generation who as adolescents had to send postcards to war criminals e.g. to Hess and who raised their own children with this kind of poison.

The infrastructure that consolidated colonialism in South Africa is intact. But what about white (progressive) people in South Africa (and the Netherlands)? To what extent are they prepared to make reparations, to compensate for the suffering, to return the stolen land?

In 2011 archbishop Tutu suggested to impose a ‘wealth tax’ for white people because all white people had benefited from Apartheid and colonialism. Also the Truth and Reconciliation Commission suggested such a tax. Most white people protested with fury. Apartheid president De Klerk (and Nobel Peace prize winner) denied that ‘white people’s privilege is solely due to the exploitation of Africans.’

In 2000 a white ANC MP, Carl Niehaus and a white lady, Mary Burton, of the Anti-Apartheid organization Black Sash, issued a statement in which white people acknowledged that black people had been driven from their land. Also this campaign was highly unsuccessful.

Stephen Bantu Biko

White progressives refused to sign e.g. writer/poet Breyten Breytenbach and former MP and white anti-Apartheid icon Helen Suzman. Suzman stated: ‘I have nothing to be apologetic about. I did not initiate the system of Apartheid I fought against.’ Mind you: her fight against Apartheid was waged by sitting in a ‘whites only’ parliament and by doing so legitimizing it. She was opposed to both the armed struggle and a struggle by peaceful means. After the elections Suzman opposed measures that were to promote black economic empowerment.

A new generation of black people continues the fight for the return of the stolen land, for the deconstruction of white supremacy and for social justice.

Steve Biko warned that the biggest mistake the black world has ever made is to believe that any opponent of Apartheid is an ally. Biko argued that the commitment of white progressives prevented black people from making progress in the struggle. Dr. Martin Luther King was wondering in his famous letter from Birmingham prison whether white progressive people were more for law and order than for justice..

Are you ready for revolution?

I/we as privileged white people learnt from the people in exile and members of the liberation organizations. Till this day I benefit from their understanding and the views of the present generation to understand the impact of being black in this white dominated world. To understand the importance of who says what on behalf of who, to understand the position of power (or lack of) that dominates your outlook on the world. Victories have been won and progress has been made solely by political action of black people and people of colour and controlled by themselves. They are the vanguard. In the Netherlands they were the ones who put racism and decolonization and all of their aspects on the agenda. And they decide ‘to kick in the way they see fit’, as Biko put it.

That is a dangerous situation in an atmosphere in which dominant opinion leaders and authorities tolerate racism, and create a dangerous environment in which serious threats to black people are being trivialized and activists are being criminalized. An environment in which anti-racism/decolonization degenerates into a narrative of white pride……. In which white allies try to prevent fundamental changes by wilful white ignorance (Mills) and wilful white innocence (Wekker). Under the pretext of e.g. being nuanced they are too spineless to just unconditionally support black activists, to defend them, to deconstruct whiteness etc. I have not seen them on talk shows in which black people were on their own and had to endure the hatred directed at them in the media.

In the 80s at the UN I was unexpectedly introduced to Stokely Carmichael/Kwame Ture by PAC comrades. We shook hands and he asked me his famous question: are you ready for revolution? I cannot remember my answer, I was blown away by the meeting and the question, but that question has always stuck at the back of my mind. Are white people ready for revolution?

© Marjan Boelsma, 15 april 2018

Azania(DISAMBIGUATION) Nolan Oswal Dennis / Final hour from Azanian Love Song Don Mattera

In conclusion some suggestions for further essential reading:

European Race & Imagery Foundation (ERIF) aims ‘to identify, analyze critically, discuss and fight negative representations and stereotypes of dark-skinned people’. ERIF’s website is a great source of information on the subject, text-wise and imagewise. https://erifonline.org/

Read critical articles by black thinkers who hold up a mirror to you and who inspire you e.g. Egbert Martina https://processedlives.wordpress.com/ and Simone Zeefuik https://lazeefuik.com/author/szeefuik/

Black Archives, a unique historical archive providing information from black and other perspectives that are often overlooked elsewhere http://www.theblackarchives.nl/

Read the highly topical OneWorld, the ‘largest Dutch journalistic website on the world and you’, led by editor-in-chief Seada Nourhussen https://www.oneworld.nl/oneworld-magazine/

Dipsaus: podcast by and for women of colour and anyone interested in dissenting views. Presented and created by Anousha Nzume, Ebissé Rouw and Mariam El Maslouhi. http://www.dipsaus.org/

Sources:

Archive Azania Komitee IISG (International Institute of Social History), Amsterdam, 1974 -1996

Christine Qunta, “Why we are not a nation’, (Cape Town, Seriti sa Sechaba Publishers, 2016)

Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms, Amsterdam http://www.cineclubvrijheidsfilms.nl/overons.htm

Apartheid Museum Johannesburg, South Africa https://www.apartheidmuseum.org/

Manon Braat and Nkule Mabasa, Tell Freedom, (Amersfoort, Kunsthal KAdE, 2018) https://www.tellfreedom.co.za/exhibition

Don Mattera, Azanian Love Song (Grant Park, African Perspectives Publishing, 2007)

Martine Gosselink, Maria Holtrop, Robert Ross, Good Hope, South Africa and the Netherlands from 1600 (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum/Van Tilt Publisher, 2017)

Melissa Weiner, Collonized Curriculum: Racializing Discources of Africa and Africans in Dutch Primary School History Textbooks (American Sociological Association, 2016)

Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: paradoxes of colonialism and race, (2016, Duke University Press)

Charles W. Mills, Global White ignorance, https://tandfhss.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/files-default/4986/9780415718967_text-chapter_23.pdf

Piet Kort, Een land apart, Zuidafrikaanse notities, (1968, Utrecht/Antwerpen, A.W. Bruna & Zoon)

Berlin to change street names over brutal African colonial past, https://www.dailysabah.com/europe/2018/04/14/berlin-to-change-street-names-over-brutal-african-colonial-past

Athi-Patra Ruga, Miss Azania – Exile is waiting, 2015. 190 x 150cm. Courtesy of the artist and WHATIFTHEWORLD/Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg. http://artafricamagazine.org/winners-11th-edition-les-recontres-de-bamako-african-biennale-photography-announced/athi-patra-ruga-miss-azania-exile-is-waiting-2015-1-190cmx150cm/