The Apartheid regime restricted freedom of the press in South Africa through legislation and other repressive measures. Also news from the rest of the world was subjected to political censorship. The South African Government Gazette regularly published lists of banned books and other publications1. Television was banned till 1976, for ‘ the effect of wrong pictures on children, the less developed and other races can be destructive2’. White and black newspaper readers were presented with separate editions. Every precaution to protect the colonial Apartheid system and to prevent resistance.

Black journalists had to work under difficult conditions. Apartheid legislation restricted them in all areas of life. Practising their profession could lead to detention, dismissal or a banning order. Salary, training and promotion opportunities were far below those of white journalists.

As a result of Apartheid legislation white journalists monopolized news coverage. The international press sent white correspondents to South Africa and relied on South African white journalists. The famous white journalist Anthony Sampson wrote in The Observer (22/6/1986) that since the declaration of a state of emergency reporters were not allowed to enter Soweto. A factual error, to say the least, because every day journalists entered and exited Soweto. They lived there because they were black.

Selective coverage is an instrument in a political struggle. That resulted in biased information on Apartheid and black resistance and subsequently in one-sided solidarity.

Faint-hearted role white media

In 1996 the senior journalists Jon Qwelane3 and Thami Mazwai4 testified before the TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission)5 in a special hearing on the role of the white media during Apartheid. Both journalists accused the leading English-language papers of collaborating with the Apartheid regime from 1960 to 1994. In particular these papers prided themselves on their Anti-Apartheid orientation.

The papers denied people access to information and according to Qwelane violated a basic right. He also pointed out the pay gap between black and white journalists. Qwelane: ‘paying different salaries determined by race for people doing the same job was blatantly discriminatory and was an obvious violation of our human rights.’

Although these papers previously supported families of journalists who ended up in prison they changed their tune in 19776. Qwelane: ‘Yet, curiously, these same media turned very angrily against us in 1977 when 27 of us, all black journalists, marched in protest against apartheid and were arrested. They did not care that it was a march of conscience and sparked, largely, by the banning of newspapers the month before and the murder of Steve Biko by the security police in the same month.’

In editorials the protest march and the grounds for the protest were condemned by the white editorial staff. The participants of the protest were given the option of non-payment of salary during their detention or taking leave. Qwelane: ‘Of course, the contradiction did not touch them at all, that our march was against the very things they purported to denounce in their eloquent editorials.’

Qwelane also acknowledges that frequently white journalists showed courage in exposing the injustices of the system, e.g. the inhuman conditions in South African prisons and the exposure of Vlakplaas7. In critical comments they condemned the Apartheid system, but they did nothing. Qwelane: ‘Yet again, as shown by our anti-apartheid march, which they never supported, those editorials were in retrospect acts of shallow self-righteousness which were very rarely matched by practice. The only conclusion I can draw in the circumstances, is that they were playing to the international gallery and they opposed apartheid only to the extent that our oppression must be made more comfortable.’

Apartheid in the workplace, in training, in news services

In spite of their Anti-Apartheid rhetoric in editorial comments the white bosses did not facilitate training opportunities and so denied these journalists promotion prospects. Qwelane testified for the TRC: ‘In very many cases the lack of training was used as a convenient excuse to deny black journalists promotion on the newspapers on which they worked. It was the policy of job reservation and practice, notwithstanding the eloquent condemnations and editorials against the policy of job reservation itself. It often, of course, depended on the goodwill of the particular editor to correct what was evidently wrong in denying blacks promotion.’

In the spirit of the policy of Apartheid also news coverage took place along racial lines. Qwelane: ‘Nearly every single one of the liberal establishment English language newspapers had a so-called Extra or so-called Africa edition. Whatever the rationalisations, these editions, Mr Chairman, were apartheid editions intended for blacks and intended to segregate news on racial lines.’

And: ‘Typically what passed for news in these editions was often regarded by news editors as being unfit for white human consumption. ..Conventional newsroom wisdom held that blacks loved to read about sex, soccer and crime. Indeed, these were normally the kind of stories that found themselves placed in the Extra and Africa editions. Apart from changing the front and back pages of a newspaper to give it the so-called black feel, important finance and business news was dropped altogether in these editions destined for the black areas, and you can go to any newspaper library, you will find what I am talking about. It is there.’

Also in the workplace these papers complied with the racist policy of Apartheid. ‘Canteen facilities and toilets were also cruelly segregated. Blacks had a separate canteen from that for whites and when we protested those protests only elicited a third canteen…..’, said Qwelane during the TRC-hearing.

MWASA Trade Union

Black journalists and other workers in the media industry organized themselves in the black trade union MWASA (Media Workers’ Association of South Africa). The acclaimed journalists Jon Qwelane and Thami Mazwai were two of its founding members. MWASA’s predecessor was the UBJ (Union of Black Journalists) which along with other organizations of the Black Consciousness Movement was banned in 1977.

In 1980 MWASA organized a successful strike for pay rise, better working conditions and recognition of the union by the media owners. It was the first strike of black journalists and other media workers. The leaders of the strike paid a heavy price. They lost their jobs and were put under house arrest for years. In spite of the improvements the high pay gap and the difference in working conditions continued to exist.

Internationally MWASA was represented in the executive committee (Thami Mazwai and Sandra Nagfaal) of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ). In South Africa MWASA joined the black trade union confederation NACTU (National Council of Trade Unions).

The NVJ (Dutch Association of Journalists) supported MWASA and joined an international solidarity action with MWASA in 1981. Later the NVJ set up a relief fund for the families concerned of black journalists.

In South Africa the journalist Mono Badela later formed the association of journalists ADJ (Association of Democratic Journalists). This association was limited to only journalists. The ADJ accepted the Freedom Charter of the ANC/UDF (United Democratic Front) and also admitted white journalists. MWASA was more sympathetic to Africanism and Black Consciousness.

In 1988 Mono Badela visited the Netherlands to obtain recognition for the ADJ instead of support for MWASA. He received support from FNV (Federation of Dutch Trade Unions). Influenced by AABN (Anti-Apartheid Movement Netherlands) and KZA ( Holland Committee on Southern Africa) FNV insisted on recognition of the ADJ and not MWASA. The NVJ continued supporting MWASA and did not enter into a relationship with the ADJ.

Pressure on black journalists to cover part of the resistance

In 1990 the South African Institute of Race Relations8 organized a seminar on press freedom in the new South Africa and an imminent new censorship. Senior journalist Thami Mazwai of the daily The Sowetan was one of the speakers. He talked about the threats to black journalists by a part of the black community. There were attempts to force journalists to exclusively report on ANC-affiliated campaigns. This undermined conscientious and complete news coverage.

Mazwai stated that perhaps 40% or 50% of the news was accurate, ‘but here is that 50% which is made up of particular positions, specific distortions and an attempt to influence the readership – the public – to think in a particular direction.’ Brutal violence and money played a dominant role in political life in the township. Mazwai: ‘..we have a problem with a lot of organizations in the country, which will not fund a project for community development unless it is proposed by a particular group.…..Student groups, if they are of a specific political organization, are given amounts like R 20 000 to run an organization. Knowing that 17-year-olds and 18-year-olds are in control of funds of this size, one can better understand what is now happening in the townships. And R 20 000 is a very conservative estimate: the number commonly cited is R 40 000.You have some of these youngsters driving around in cars, with loads and loads of money in their pockets, and when you try and find out where they got it, you discover it comes from a certain overseas funding organization9.’

Mazwai tells how abroad an AZAPO-representative was not allowed to speak at a protest rally for the Sharpeville Six on death row10, even though this person recently came from the country and knew more about the matter than anyone else. It was said that AZAPO was not part of the struggle despite the fact that AZAPO-members were in prison. And so someone from the Anti-Apartheid movement who had never set foot in South Africa addressed the crowd.

Mazwai: ’We have now reached a point where the journalist is told, you are either for us or against us. It’s sheer political blackmail. Many of us have been in jail several times, and we don’t mind going to jail if it is in the pursuit of what we believe in.’ And: ‘..not only do I have to defy the government, I also have to present the facts in such a way that I am seen to be pushing a particular organization. Many of us have said we simply cannot have this.’

At some point The Sowetan became the target of a boycott campaign. The paper would allegedly exclusively report on AZAPO and PAC. Mazwai explains how this worked: ‘What happened was that I got a visit from some prominent activists who said: Your newspaper is the only one writing about the PAC and AZAPO. Why are you giving life to organizations that don’t exist? My response was: We are reporting on meetings being held by these organizations, and if at all of you say they don’t exist, what about the people who attend those meetings? Are you saying that we should not report on those meetings. They said, it is only a few people going there. I said, the same number of people go to your meetings as go to these meetings, if not the same people. They said: But you are dividing the oppressed. We must only have one organization. So I said: Who decides on this one organization?’

The Sowetan did not allow themselves to be pressured and continued reporting on the ANC, PAC and BCM. Furthermore they started a campaign for press freedom. Mazwai: ‘..because we believe that freedom is indivisible. Freedom cannot be applied at one level while at another level we have suppression.’ The threats did not stop. Mazwai tells that Sowetan journalists were threatened with e.g. necklacing11 and throwing petrol bombs to their houses. Mazwai: ‘We used to get calls at night in which we were told what some people thought of us. One night I got a telephone call (Jon Qwelane got a similar call) to say I was going to be attacked, and I had to take my wife and children away to my mother’s place, so if these people came then whatever happened to me, my children would not be exposed to it. But I was certainly not to leave my house, because that would have been a sign of weakness on my part. What freedom are we talking about if we are going to be told ‘This is how we think’? That is not my job as a journalist. I am not here to come and tell you what to think or how to think. I am merely here to give you the information on which to make whatever decisions you have to make on any one day.’

During the discussion at the seminar Kaiser Nyatsumba (senior journalist of The Star) pointed to the uncritical attitude of white liberal journalists towards this issue: ‘Many whites who embraced the ANC as the future government were trying to be in the good books. …white liberals, he said, were guilty of this-they would not attack anything ANC-aligned, for fear of having their liberal credentials questioned’12. What is striking is that the ANC through newspaper ads encouraged people to support its acts of resistance.

Netherlands

For news from South Africa the Dutch media relied on their own (white) correspondents and white South African journalists, such as Allister Sparks and Henri Serfontein. Several times the Azania Komitee and Herbart Ruitenberg13 asked unsuccessfully to have black journalists cover the situation. If not, they would miss the opportunity to have correspondents who lived and worked in the heart of the black community, an impossibility for white journalists during Apartheid.

Following is an interview from the archives of the Azania Komitee with Jon Qwelane in Paris 1986. It was published in Azania Vrij14, a periodic publication of the Azania Komitee.

____________________

© Marjan Boelsma, 23 February 2021

Translation into English: HippoLingo

Reproduction of articles or parts of articles is authorized, provided the source is acknowledged and that passages and quotations are not placed in a different context

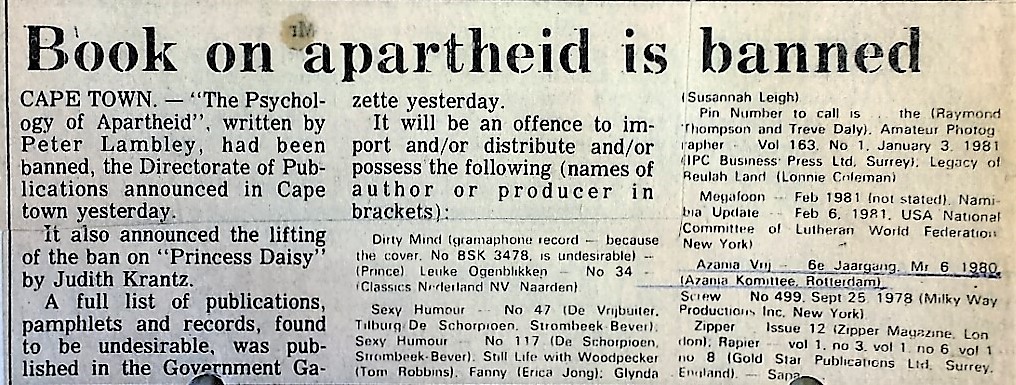

Azania Vrij on list of banned books. Rand Daily Mail, 14 March 1981

1986

Jon Qwelane (1952-2020) on Apartheid and the media

‘To exercise the profession of a journalist is an almost impossible task for a black person.’ Jon Qwelane, black and a journalist, talks about the black union for media workers, MWASA, censorship and the current state of emergency. He was in Paris on the occasion of the International Conference on Sanctions against South Africa in June this year (1986). During the interview he also commented on the selection of news by foreign correspondents, who displayed a strong bias in favour of the ANC.

Legislation and news coverage

Legislation by the government, even before the current state of emergency, makes it hard for journalists to cover the situation in the black areas. Jon Qwelane lists a number of those laws:

‘The Police Act for instance states that everything written about the police must be beyond reasonable doubt, so absolutely correct. However, it does not say what is meant by reasonable doubt. So the bottom line is you can write about the police when they approve. Then there is the Prisons Act which says you must not report on what is going on in South African prisons. For example people are tortured, but you are not authorized to write about that until the police and the prison authorities have given their version. But we know they have never ever given ‘their version’. In addition there is the Inquiry Act. When somebody dies from something other than natural causes, which basically means ‘at the hands of the police’, we cannot publish how that person’s life came to an end or succumbed to which injuries. Only after investigation we can write about that. People die in many ways, for many reasons, but you just cannot tell the world about it. Even the victims’ families cannot be informed until the regime authorizes the media.’

State of emergency

A few days before Qwelane left for Paris the South African regime declared a state of emergency. ‘Now we cannot publish the names of those who have been arrested, nothing that might reveal their identities. Even if it was my wife I cannot write about that. You can publish only after approval from the authorities. Nor can you report on what the police are doing in the townships.’ What little there was left of press freedom has been completely eliminated by the proclamation of a state of emergency. ‘Any news you get now comes from the government. Journalists will be given news from the Department of Government Communications in Pretoria and Pretoria police HQ. Needless to say that that news is distorted.’

The South African government also prohibits publication of what is called subversive statements. Newspapers have no idea what that implies, because the government refuses to clarify what is meant by subversive activities or coverage. So in Qwelane’s view publishing is an ‘extremely dangerous activity’. ‘For instance, I live in Soweto, but as a newspaper reporter I am not supposed to be there at all. Without permission from the authorities I cannot do my job anywhere in the country. Not even in my own garden, simply because it is situated in Soweto.’ Qwelane also adds that South Africans who are in favour of imposing sanctions run the risk of being sentenced to 20 years imprisonment in the worst case.

Detained and banned

The government’s control over the news is virtually unlimited. Press passes are issued by the police. A number of black journalists was denied a press pass. Qwelane has never applied for a press pass. He says: ‘That means I am doing my job illegally… Black journalists have been frequently imprisoned. For example, Joe Thloloe of The Sowetan has been arrested and jailed so many times that he has lost count. He has also been banned. Mathata Tsedu has been banned and has been detained without due process. Personally I was arrested together with a colleague, Michael Tissong, when we were covering the school boycott. We were told we were risking imprisonment for any length of time next time we would be found near schools that were being boycotted.’ It is therefore not surprising that ‘many journalists live in exile’

White and black news

Qwelane says that South African newspapers subdivide their readership along racial lines. The news content of black newspapers, e.g. The Sowetan and City Press, is different from that of white newspapers, although white newspapers do have black readers. Even the newspapers run by whites and focusing on a white readership have black editions. ‘So we have two editions of the same newspaper with different reports on the front page. One half of the population does not know what the other half thinks and how it lives.’

Selection of news

On top of the regime’s censorship the news is also selected by journalists. Qwelane: ‘There are various political forces in South Africa. All foreign news agencies follow an ideology, a political organization in the country and create an image making it appear as if that is the only representative movement and political organization. Even if this image is completely false. The domestic media are to a large extent responsible for this. It is white people that select the news for abroad. They do not omit information because that is not newsworthy, but because it does not serve their purpose. So the correspondents only write about things they want you to know and not about what you should know. In addition to the restrictions imposed by South African legislation this is a second level of self-censorship by the foreign media.’

Two political ideologies

According to Qwelane there are two distinct political ideologies within South African resistance. One is stated in the Freedom Charter (1955), adopted by the ANC among others and forming the political basis for the UDF. The other ideology is Africanist Nationalism, propagated by the PAC. Qwelane: ‘In the country it is propagated by a number of organizations of which I cannot give the names, because if I do they may be accused of furthering the goals of a prohibited organization.’ Closely aligned with Africanist Nationalism is the Black Consciousness Movement as propagated by AZAPO and its student wing AZASM. Qwelane feels that is the reality. ‘The UDF and its Charter do not give evidence of being a socialist party, whereas the Africanists and the Black Consciousness Movement do. The white media are worried about nationalizations under socialism… The white businessmen who own newspapers are trying to secure their future existence. That is why they rather promote the other political ideology, since that one still offers opportunities for capitalism.’

MWASA

Jon Qwelane is co-founder of MWASA (Media Workers’ Association of South Africa). MWASA organizes black journalists and workers in the media industry. Jon Qwelane: ‘We started with the Union of Black Journalists, which was prohibited in 1977. Then we formed WASA (Writers’ Association of South Africa), which restricted itself to just organizing journalists. In 1980 at the congress in Cape Town it was decided to open the union to anyone from the black community working in the media industry. At the time there were no unions that could legally organize these people. After extending our membership we were renamed MWASA.’

White solidarity

‘In 1980 there was a strike. The dispute was about wages, working conditions and recognition of the union by all employers. The strike lasted 8 weeks. In the end all our demands were met.

During that strike we asked white journalists to initiate solidarity actions. White journalists are organized in the SASJ (South African Society of Journalists). The SASJ was split into two groups. The left wing wanted to go on strike, but the right, conservative wing said: ’No, no strike!’ As it turned out the SASJ did not go on strike, but refused to take over the strikers’ jobs.’

In order to prevent South Africa from heading towards disaster Qwelane urges ‘the government to admit all political parties, release imprisoned political leaders and resign itself. The people in my country should be given the opportunity to elect their own government. We have a government that refuses to listen and does not acknowledge black grievances. They want to reform apartheid instead of ending it. But how can you tame a crocodile? It might be tamed for an hour, but the next second it will bite you. The government believes it can satisfy black aspirations with a minimum of reforms. Black people are not interested in that.’

Notes

[1] The publication of the Azania Komitee also ended up on the list of banned publications. See illustration.

[2] Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd compared television with nuclear bombs and poison gas, claiming that ‘ they are modern things, but that does not mean they are desirable.’ Minister Albert Hertzog also argued against the introduction of television that ‘South Africa would have to import films showing race mixing; and advertising would make Africans dissatisfied with their lot’. https://nl.qaz.wiki/wiki/Television_in_South_Africa

[3] Jon Qwelane (1952-2020) was an outspoken critic of the Apartheid regime and he was persecuted for that. He was co-founder of MWASA and was an executive committee member of the IFJ. Among other things he wrote articles and columns for The Star and Sunday Star. He supported the PAC (Pan Africanist Congress). Later he represented South Africa as ambassador in Uganda.

[4] Thami Mazwai (1944) was in the days of the Apartheid regime an influential critical journalist at The Sowetan. In 1982 he was sentenced to two years in prison because he refused to testify against Khotso Seatlholo, leader of SAYRCO (South African Youth Revolutionary Council) who was facing charges for terrorism. Mazwai was co-founder of MWASA and was also an executive committee member of the IFJ.

[5] https://www.iol.co.za/sundayindependent/dispatch/jon-qwelanes-own-words-before-the-trc-5afb9322-ef05-426d-bf25-b6a57d0793e7 Black journalists are denied training and promotion, veteran journalist Jon Qwelane told the TRC hearings in 1997. The TRC is also known as Truth Commission or Reconciliation Commission.

[6] On 19 October 1977 the Apartheid regime banned 19 organizations of the Black Consciousness Movement and the black papers The World and Weekend World. Black journalists and activists were detained. That day is known as Black Wednesday and is now annually commemorated as National Press Freedom Day.

[7] On Vlakplaas as their headquarters were based in secret death squads which were responsible for numerous assassinations and attacks on (mostly black) opponents of the Apartheid regime. Political opponents were tortured or they ‘disappeared’. Their method was to burn or blow up their bodies multiple times and to dig secret and anonymous mass graves on the site of the farm.

[8] Mau-mauing the media: New Censorship for the New South Africa, South African Institute of Race Relations, Braamfontein Johannesburg, South Africa, 1991. Reprinted in 1992. The book includes ‘transcripts of the talks and discussions at the seminar’.

[9] See also Soweto uprising 1976 One-sided international solidarity – Tegen het vergeten

[10] Sharpeville Six Save the Sharpeville Six Actions against death sentences Sharpeville 6 and Upington 14 – Tegen het vergeten

[11] Necklacing meant that a burning rubber tire was forced around the victim’s chest and arms. It usually resulted in death.

[12] Mau-mauing the media: New Censorship for the New South Africa, South African Institute of Race Relations, Braamfontein Johannesburg, South Africa, 1991. Reprinted in 1992. The book includes ‘transcripts of the talks and discussions at the seminar’.

[13] Herbart Ruitenberg (1936-2020) was co-founder of Amnesty International The Netherlands and the first editor-in-chief of Wordt Vervolgd. He was active in the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Partij van de Arbeid (Labour Party) and secretary of Steun Democratische Krachten. He worked together with the Azania Komitee.

[14] Azania Vrij, nr. 2, 12th volume, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, July 1986.