SkotavillePublishing

SkotavillePublishing

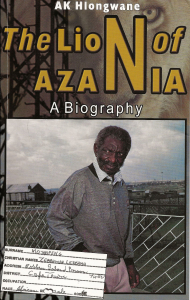

Hlongwane describes the incredible life of PAC1 leader Zephania Lekoame Mothopeng aka Uncle Zeph. His whole life he fought against the colonial Apartheid regime. That implied prison sentences e.g. two times Robben Island, solitary confinement and unprecedented torture. His friend, the writer Es’kia Mphahlele: ‘I know of no activist in this country whose body has been savaged for so long a period as was yours.’

The leading western Anti-Apartheid movements remained silent on Zeph Mothopeng and refused to support him and his movement2. This well-documented political biography illustrates how unjust and harsh that silence has been.

Dr. Ali Khangela Hlongwane is researcher at the History Research Group of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Letter from a daughter

The book opens with a poignant letter from his daughter Sheila Masote3 to her deceased father. She describes the impact of Mothopeng’s resistance work on his family. She writes how initially she grew up in a rich social and cultural environment, how that changed when her father was in prison more frequently and eventually was severed from his family for the larger part of his life. ‘I have been angry with you for far too long now, Papa. I have had too ‘whys/’, ‘hows’? and how dare yours/ and the ultimate: choosing Sechaba (nation) over us, your family and over ME!’ She tells about her anger how she and her mother, Urbania (Bebe) Mothopeng4, were excluded from his political activities, and not her brothers, for security reasons and because they were women. Till her mother demanded to be involved. ‘I felt betrayed by you Papa, and by the perceived unexpected male chauvinism from you, my ever liberal dad.’

Under the Terrorism Act Sheila herself was held in solitary confinement where she had a miscarriage. Mature and as a result of her experiences in prison she later understood the role of her parents and the PAC in the liberation struggle. ‘Pride swelled in me, tempering the pain and self-pity. I came to understand you, your fight, resilience and dedication to the liberation of Africa and its people.’

Zeph Mothopeng’s year of birth coincided with the proclamation of the Land Act in 1913. The Land Act was preceded in 1910 by the Union of South Africa confirming the political and economic power of the white minority. The Land Act was the prelude to a traumatic relocation policy and further expropriation of the land of the African majority. In this way land grabbing, started by Jan van Riebeeck in 1652, continued and was given permanence. It marked Zeph Mothopeng’s life, body and soul. Unflaggingly he would fight for the restitution of the stolen land, the liberation of Azania (South Africa) and Africa.

Zeph grew up with five brothers and sisters. Father was a police officer and mother produced and sold clay pots to earn some extra money. Zeph was their youngest child. He did domestic chores, so not until at the age of eleven could he attend school. He saw from nearby how his parents impoverished.

In high school he developed into a fierce debater against injustice ‘predicting doom to South African white rule and British imperialism’. The later ANC leader Oliver Tambo, the writer Es’kia Mphalele and the later PAC leader Peter Raboroko were his schoolmates.

In 1943 Mothopeng became an active member of the ANC and a year later of the then formed ANC Youth League. The Action Plan of the Youth League was later adopted by the ANC. With a more radical policy of resistance with e.g. acts of civil disobedience, protests and strikes they fought and opposed the Apartheid regime.

Mothopeng became a well-liked teacher (maths and physics), choirmaster, he composed and enjoyed ballroom dancing. All that did not interfere with his militant opposition. He married Urbania. Together they had 4 children. Urbania was active as a musician, conductor, teacher, social worker and family planning consultant. Of the 50 years they had been married they could spend just 17 years together because of imprisonment and ‘banning orders’.

In 1951 Mothopeng was elected President of TATA (Transvaal African Teachers’ Association). Under his leadership TATA organized campaigns against so-called Bantu education which the Apartheid regime wanted to introduce. They travelled all over the country to make teachers and parents aware of the dangers of the new educational system for the African child. Bantu education aimed at preparing children for unskilled and inferior jobs, suited for their ‘race’. After all, they were inferior to the white population. Hendrik Verwoerd5 headed the Native Affairs Department and introduced the Bantu Education Act in 1953. He declared that Bantu children did not have to learn maths for there would not be any jobs for them and they would never have equal rights. These schools were financed by tax money from the African communities. In reality that was a fraction of what white schools could spend. The impact of this policy is that these days black people are still trying to catch up on these educational disadvantages.

In 1952 Mothopeng was one of the organizers of a boycott of the Jan van Riebeeck celebrations. People celebrated the fact that 300 years ago Jan van Riebeeck set foot in South Africa. A fact which was also shamelessly spectacularly celebrated in the Netherlands.

His radical position and subsequent political activities lost him his job. He could no longer teach in South Africa. For his work as a teacher Mothopeng moved to Basutoland (Lesotho), then still a British protectorate. But there he also had to leave because of his political activism. Back in South Africa he worked at that time e.g. as a warehouse worker and as a clerk for a law firm.

Mothopeng belonged together with Robert Sobukwe, A.P. Mda, Anton Lembede and some others to the Africanists, a radical group within the ANC who wanted to realize the Programme of Action6 without any compromise. Dissatisfied with the moderate ANC course, underlined with the adoption of the Freedom Charter and the moderating influence of white communists, Mothopeng together with them participated in founding the PAC in 1959.

In 1955 the ANC adopted the Freedom Charter together with the South African Indian Congress (SAIC), the Congress of Democrats (COD) and the South African Coloured People’s Organization(SACPO). The latter organizations received in this Congress Alliance as much representation as the ANC that represented a much more extensive support base. The Africanists objected to this undemocratic course of events. They also rejected the content of the Freedom Charter. The Charter states that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white. The Africanists considered it naive to think that the oppressed Africans were equal to their European ‘overlords’. For Zeph Mothopeng the population in South Africa is made up of the oppressors and the oppressed and in this situation association with the oppressors was out of the question.

The Congress of Democrats was mainly made up of white communists from the banned South African Communist Party (SACP/CPSA). The Africanists criticized the party because it refused to acknowledge there was a colonial situation in South Africa and an anti-colonial liberation struggle. In 1922 this party supported a strike of white miners calling for unity with white workers for a white South Africa. Criticism of the SACP of the Africanists and later the PAC had nothing to do with anti-communism and anti-socialism. According to Hlongwane there is no evidence of anti-communism or anti-socialism in the PAC documents. Mothopeng saw the SACP as so-called communist, a party that hid behind the ANC, influenced its political process and barely able to organize people.

Allegations of anti-communism or racism were used as arguments of many western Anti-Apartheid movements to withhold support for, and even sabotage7, the PAC. In 1989 Mothopeng spoke in London at a big rally organized by a.o. the PAC and the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group. The hall was packed8.

The British Anti-Apartheid movement did not join the rally. Hlongwane quotes Carol Brickley of the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group who summarized what they would have missed if they had come: ‘Had they done so they would have destroyed at least three of their myths about the struggle in SA: (1) that the PAC is a racist organization, (2) that it is anti-communist and (3) that the Soweto uprisings were a spontaneous outburst of anger which was politically unled.’

Mothopeng was an advocate of a non-racial socialist government: ‘Which will deal with the paramountcy of the economic interests of each individual… I do not want to go into detail, because economics is a living science in a practical world.’ He refused to be carried away with the rhetoric and doctrines what that socialism should look like. ‘Socialism is a broad subject….. Socialism depends ultimately on the peculiar circumstances of those who wish to implement those broad principles.’

In 1960 Mothopeng was sentenced under the Suppression of Communism Act for his part in the PAC campaign against the Pass Laws9 .

Service, Suffer, Sacrifice is at the heart of the PAC code of conduct. Mothopeng was living proof of this motto but paid a high price. This motto is originally from West Africa, Hlongwane says. In the 1940s Kwame Nkrumah led there The Circle, a centre for revolutionaries from all over Africa.

After the campaign against the Pass Laws the PAC was banned in 1960 and went underground. Hlongwane describes in his book the extent and activities of the underground network of the PAC. In 1963 Mothopeng’s arrest led to his first prison sentence on Robben Island. Mothopeng was arrested with many other PAC members all over the country. They were accused of armed resistance organized by POQO/PAC10. His son Loxley, also active in POQO, managed to flee the country in time.

During his pre-trial detention Mothopeng was in solitary confinement and was subjected to electroshock torture, caning and a canvas bag over his head pulled so tight till he nearly choked. A former fellow prisoner described how he saw Mothopeng, screaming in a straightjacket, rolling around in the courtyard.

The conditions on Robben Island were barbaric when Mothopeng arrived there for the first time in 1964. E.g prisoners were buried with their heads just above the ground. White guards forced them to open their mouths to urinate in. Hlongwane elaborately describes the situation on the Island, the political prisoners of the various liberation movements and their activities.

Mothopeng organized there political and academic training. Together with Andrew Masondo of the ANC he took the initiative to develop impromptu classes in writing and reading. Of course there was no teaching material.

The first time Mothopeng was on Robben Island for three years and was then subjected to a ‘banning order’11. About 350 kilometres away from his family he was provided accommodation in a corrugated iron shack: ‘It was cramped, uncomfortable and barely big enough to accommodate the basic bedding he could organize. He was not provided with cooking utensils and was left with the message that he should look for some form of employment to help him make a living.’ He could not attend or address meetings or social gatherings. He was also barred from entering factories and educational institutions.

In the 1970s Mothopeng maintained close contact with organizations of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). He spoke at some of their gatherings. In 1974 he was one of the speakers at a BPC conference (Black People’s Convention) in Durban. At the conference it was suggested to organize the Frelimo Rallies out of solidarity with the liberation struggle in Mozambique. In 1975 he spoke at the BPC congress. There he condemned the collaborating Urban Bantu Councils, the South African Indian Council and the Coloured Representative Council: ‘they are (all) a waste of time. We will never have anything to do with them’.

In 1979 he was once again sentenced to Robben Island. Mothopeng was the chief suspect in the lengthy (1977-1979) and largely secret Bethal Trial12 where with 17 co-defendants he was charged with organizing the Soweto uprising in 1976. Four of the defendants died by torture in police custody.

The Apartheid regime characterized Mothopeng as a ‘corrupter of youth’. The judge sentenced Mothopeng, by then 68 years old, to imprisonment on Robben Island for the second time. In previous trials convicted political leaders such as Sobukwe (PAC), Mandela (ANC) and Toivo ya Toivo (SWAPO) were offered the opportunity to make a closing statement. Zeph Mothopeng was denied that opportunity. He managed to smuggle out his handwritten defense. He concluded his statement with: ‘We approach prison with full certainty that freedom is at hand.’ He was sentenced to twice 15 years on Robben Island.

During his time in police custody in 1976 he was again subjected to gruesome torture. A quote from the report of the TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission):

‘The Commission heard that PAC member Zephaniah Lekoane Mothopeng suffered torture at the hands of unknown security policemen while in the Pietermaritzburg prison for his involvement in the 1976 Soweto uprising. During his torture, a policeman placed a sharp knife on his head and gently beat the knife down with the palm of his hand. He was also forced to lie on ice, and was placed in a sack and spun around in the air. With his hands and feet shackled to a stick, Mothopeng was suspended from the ceiling and spun around. This became known as the ‘helicopter technique’.’

On Robben Eiland Mothopeng became seriously ill. The regime was willing to shorten his prison term but demanded from him to renounce the armed struggle. He refused. In the meantime, the youth organization AZANYU (Azanian Youth Unity), the women’s organization AWO (African Women’s Organisation) and the trade union NACTU (National Council of Trade Unions) were campaigning for his unconditional release. At the end of 1988 he was released on humanitarian grounds. However, rallies organized by the welcoming committee where Mothopeng was to speak were banned.

Meanwhile, the collapse of the Eastern Bloc was imminent. The policy of perestroika of the Soviet Union, aimed at disarmament, also had implications for the armed struggle of the ANC that heavily depended on the Soviet Union. It was the beginnings of negotiations with the Apartheid regime. Mothopeng, since 1986 President of the PAC, was very skeptical. He said: ‘The changed climate of rapprochement can easily fool you into believing that the struggle is now expected and possible to be resolved through rapprochement’. He pointed out that since the PAC was founded in 1959 it had always relied on the strength of the oppressed and dispossessed masses. The armed struggle would not be suspended until a position had been attained that the enemy was left no other option but to negotiate and a situation in which restitution of land and elections based upon one man, one vote would be the central points. In 1989 the OAU (Organization of African Unity) adopted the Harare Declaration resulting in negotiations with the Apartheid regime without conditions regarding restitution of land. Eventually the PAC agreed to join the negotiations on a constitutional assembly based on one man, one vote.

After his release Mothopeng travelled to Europe and the United States for medical treatment. Initially he was refused a passport. Later he got one after all. Despite his illness he spoke on behalf of the PAC at e.g. UN meetings, the Black Caucus in the American Congress in Washington and at the earlier mentioned big public event in London.

The death of Mothopeng in 1990 coincided with the official abolition of Apartheid but the stolen land he had fought for his entire life had not yet been redistributed. Walter Sisulu (ANC-veteran), comrade in the Youth League and fellow prisoner on Robben Island said: ‘The oppressed are poorer after Mothopeng’s death.’

Dr. Ali Hlongwane

Ali Hlongwane wrote an urgent and moving book about the life of Zeph Mothopeng, an important and principled leader in the struggle against the Apartheid regime. A man who retained his warmth and humanity and with the courage of a lion suffered the virtually inconceivable.

AK Hlongwane: The Lion of Azania – A Biography, Skotaville, March 2021. mahtpublishing@gmail.com

___________________________________________________

© Marjan Boelsma, 18 January 2022. Translation into English: HippoLingo.

Reproduction of articles or parts of articles is authorized, provided the source is acknowledged and that passages and quotations are not placed in a different context.

[1]Pan Africanist Congress

[2] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/13/apartheid-antiracisme-dekolonisatie-2/

https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2019/08/25/soweto-uprising-1976-one-sided-international-solidarity/

[3]Sheila married Michael Masote who started the first black orchestra Soweto Symphony Orchestra, then the Soweto String Quartet and the Mmabatho Youth Orchestra ACOSA. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/the-mercury-south-africa/20110125/281956014243867

[4] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2021/10/30/women-in-the-liberation-struggle-of-azania-south-africa/

[5] Hendrik Verwoerd was Prime Minister of South Africa from 1958 to 1966

[6] Drawn up by the ANC Youth League and adopted by the ANC in 1949

[7] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/13/apartheid-antiracisme-dekolonisatie-2/

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BUcQRP2U7Sk Highlights of the rally held on 6 July 1989 in London honoring the President of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC), after his release from prison in November 1988. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=39k3563EBy4 Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms interviewed the PAC President in London 1988. This video contains some of the highlights of that interview

[9] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/

[10] POQO, later APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Army), was the armed wing of the PAC

[11] A ‘banning order’ entailed restrictions on your freedom of movement and freedom of speech, restrictions on attending meetings, on the number of people you could receive and you could only live in a place allocated by the regime, generally far from your family

[12] More about the Bethal Trial: https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2019/08/25/soweto-uprising-1976-one-sided-international-solidarity/