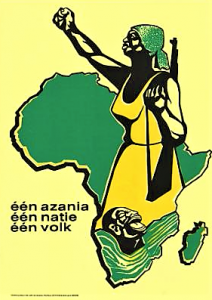

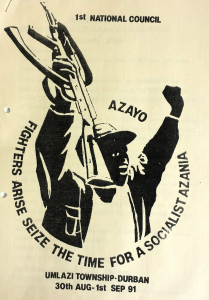

[1] Pan Africanist Congress

[2] Azania Vrij, Volume 1, no 4, June/July 1975

[3] Elisabeth Landis quoted by Elisabeth Sibeko

[4] Black Consciousness Movement

[5] Oshadi Mangena in ‘Eurocentric development and the imperative of women’s emancipation in Sub-Saharan Africa’ (An Introduction to an Alternative), 1996

[6]Lesley Lawson, Werken in Zuid-Afrika, zwarte vrouwen aan het woord, feminist publishing house SARA, Amsterdam 1986. Original title Working Women. A portrait of South Africa’s black women writers. Ravan/The Sached Trust, Johannesburg 1985. Text and photography Lesley Lawson, translation by Eva Wolff

[7] Sharpeville 21 March 1960 Protests against the pass laws, PAC, the Sharpeville massacre, uprising in Apartheid South Africa, and effects – Tegen het vergeten

[8] The Bantustan or homelands policy meant that the regime divided along ethnic lines 13% of the country into 9 Bantustans for the black majority. Each one would allegedly be granted independence. The residents became against their will citizens in the territories allocated by the regime. In October 1976 Transkei was the first one to be declared independent. 44% of these residents worked in the mines and white urban areas. Transkei did not have a viable economy and consisted of large parts of infertile land. In reality the homelands were reservoirs of cheap labour and a dumping ground for non-productive black people such as the elderly, the sick and children. Transkei’s independence was not internationally recognized. The banned liberation movements PAC and ANC vigorously rejected the Bantustan policy. SASO – and the rest of the Black Consciousness Movement – also vigorously rejected the Bantustan policy, an instrument against black political unity against the Apartheid regime

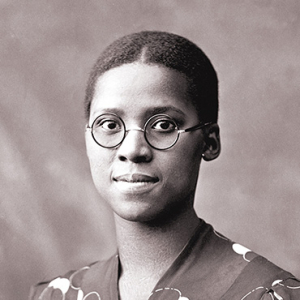

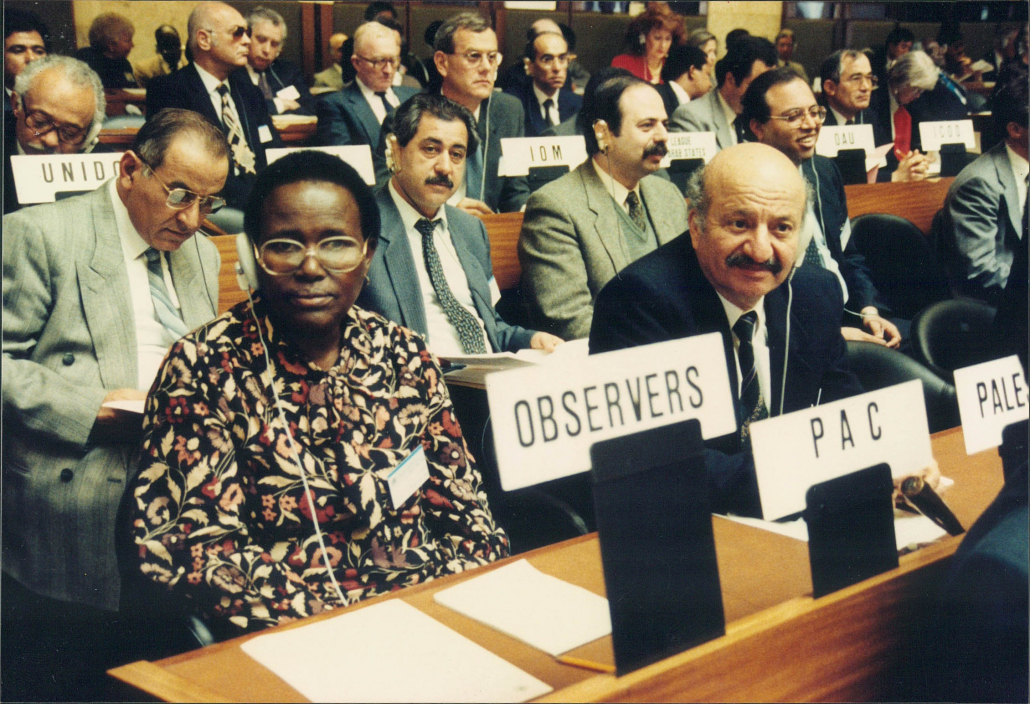

[9] Elisabeth Sibeko (PAC) at the UN World Conference in Mexico City in 1975 during the International Women’s Year, Azania Vrij, Volume 1, no 4, June/July 1975

[10] Idem ’When in 1957, Dr Ntantala-Jordan was requested to contribute an article for a magazine called Africa South on ‘African women’, she chose to write about the ‘other women whom nobody ever hears about, whose story had never been told, because they are not the ‘pillars’ of their societies’. According to her, these ‘were some of the girls I had grown up with, now married and living the lives of widows, as their menfolk were away in the cities’ (1992: 164). Her second article in this magazine was entitled ‘The Widows of the Reserves’. http://www.humanities.uct.ac.za/news/tribute-late-dr-phyllis-priscilla-ntantala-jordan

[11]Ena Janse, Bijna familie, De huishoudster in het Zuid-Afrikaanse gezin, Dutch translation 2016 published by Cossee BV, Amsterdam. Original title Soos familie. Stedelike huiswerkers in Suid-Afrikaanse tekste. Published in 2015 by Protea Boekhuis, Pretoria

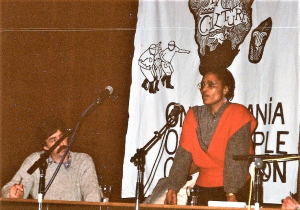

[12] Umtapo seminar Taking steps to challenge the oppression of women, 1993 in Durban, South Africa

[13] Umtapo seminar Taking steps to challenge the oppression of women, 1993 in Durban, South Africa

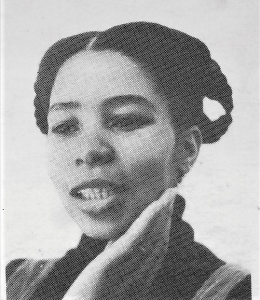

[14] Shumikazi Jako, 16 May 1982 Azania Vrij, Volume 9, no 2/3 1983

[15] South African Security

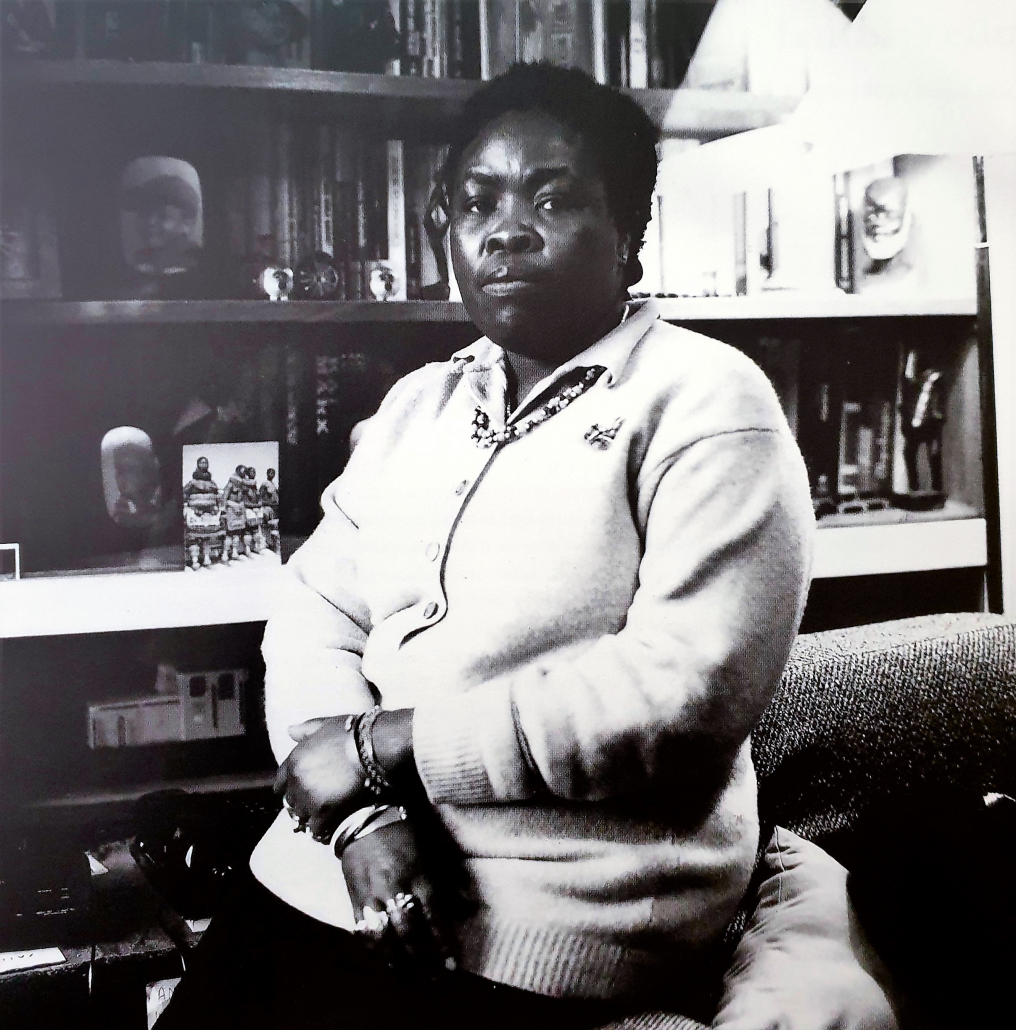

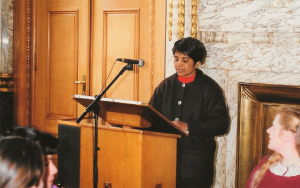

[16] Buni Sexwale was president of the South African Cultural Centre (SACCC) in Amsterdam. She was one of the speakers at the Sharpeville Commemoration in Nijmegen in 1991 Sharpeville (part 2) Solidarity with the liberation struggle in Azania/South Africa and fight against racism in the Netherlands, 1975 – 1992 – Tegen het vergeten

[17] idem

[18] Sowetan, 14/4/1992

[19] https://mg.co.za/article/2018-08-24-00-bcm-women-led-from-the-front/

[20] Speech at AALAE Women’s Network General meeting 1993. Theme African Women; Identity, Culture and Transformation

[21] Mojanku Gumbi was then AZAPO Head of Legal Affairs

[22] Sowetan, 9/11/1993

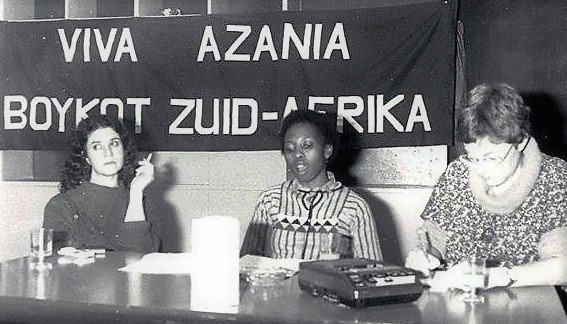

[23] The seminar was attended by PAC women (in exile) from Botswana, Zambia, Tanzania, Gambia, Australia, United States, Germany, England, Denmark and Switzerland. The Black Consciousness Movement was represented by two women from Botswana. The ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union), the liberation movement from Zimbabwe was represented by two participants. Rita Grijzen, of the Azania Komitee, participated as an observer. For Azania Vrij she wrote a report on which the information is based

[24] Azania Vrij, Volume 6, no 4/5 1980

[25] After the protest against the Pass Laws and the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960. Sharpeville 21 March 1960 Protests against the pass laws, PAC, the Sharpeville massacre, uprising in Apartheid South Africa, and effects – Tegen het vergeten

[26] Christie Douts Qunta, Hoyi Na! Azania, poems of an African Struggle, 1979, Marimba Enterprises, Surry Hills, Australia

[27] Christine N. Qunta, Women in Southern Africa, edited by Christine Qunta, 1987, Allison and Busby Limited, New York, NY. In association with Skotaville Publishers, Johannesburg

[28] Christine Qunta, Why we are not a nation, 2016, Seriti sa Sechaba Publishers, Cape Town.

[29] In the wake of this protest the UN Special Committee against Apartheid declared 9 August International Solidarity Day with the struggle of women in Namibia and South Africa

[30] SASO: South African Students’ Organization, BPC: Black People’s Convention, NAYO: National Youth Organization

[31] These days the more accepted term for the Third World is The South

[32] https://mg.co.za/article/2018-08-10-00-nomvo-poqokazi-booi-a-mother-of-the-struggle/

[33] Freedom fighter Nomvo Booi (1929-2016)‘I never doubted whether or not to continue the struggle’ – Against Forgetting

[34] UN Third Committee. This committee deals amongst other things with ‘questions relating to the advancement of women, the protection of children, indigenous issues, the treatment of refugees, the promotion of fundamental freedoms through the elimination of racism and racial discrimination, and the right to self- determination.’ https://www.un.org/en/ga/third/

[35] Sharpeville 21 March 1960 Protests against the pass laws, PAC, the Sharpeville massacre, uprising in Apartheid South Africa, and effects – Tegen het vergeten

[36] Imam Abdullah Haron died in a police cell on 27 September 1969. He had been in solitary confinement for 123 days and was subjected to daily interrogations and torture

[37] David & Elisabeth Sibeko Foundation

[38] Later APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Army)

[39] David & Elisabeth Sibeko Foundation https://www.facebook.com/davidandelizabethsibekofoundation

[40] Nadine Gordimer (1923-2014), white South African author. In 1991 she was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature

[41] David & Elisabeth Sibeko Foundation https://www.facebook.com/davidandelizabethsibekofoundation