She thought it was of no importance. But when asked again Nomvo Booi told us: eleven times she had been in South African prisons, she had been subjected to torture and had spent nearly one year in solitary confinement.

At a very young age she had become active in the liberation struggle, first in the ANC1, later in the PAC2 of which she was one of the founding members and became a member of the Central Committee. She belonged to the first female cadres of APLA/POQO3 and was, among other things, regional secretary of the underground PAC in the Transkei.

During the celebration of the International Women’s Day on 8 March 1983 in London Nomvo Booi passionately pleaded for a borderless one Africa. Both an activist and unassuming woman who died in 2016 at the age of 87.

In London, 1983, Irene Scheltes (Azania Komitee) had an interview with Nomvo Booi4.

Nomvo Booi in 1988. (Pic Azania Komitee)

ANC, PAC, POQO/APLA

Nomvo, can you tell us about your political activities? How did it start and how have things worked out?

‘At a very early age I became a member of the ANC. I was involved in the successful ‘Defiance Campaign’5 in 1952. What a great massive power emerged there! At the time I was a member of the ANC Youth League. They believed that the ANC leadership had stopped the campaign too soon and too easily. This Youth League formed the basis for the PAC, formed in 1959. I was deeply involved in its formation and I became a regional secretary of the PAC. During the Positive Action Campaign of 1960, which culminated in the Sharpeville Massacre6, I lived in Queenstown. There I was arrested at a PAC demonstration against the Pass Laws. I was sent to prison for four months. Straight afterwards I went underground, working for POQO. Back then I was one of the few female cadres in POQO.’

‘After my imprisonment I could not get a job in Queenstown, and therefore lost the right to live there. In 1961 I found myself in the Transkei. There too I continued working underground for POQO. In August 1962 I was arrested again, accused of PAC activities. I was initially imprisoned for 90 days without due process, without my family being informed, without extra clothing, without anything to read. The 90 days were extended to 270 days and then to eleven months. All that time I was in solitary confinement and was constantly beaten.’

When asked what kind of torture Nomvo was subjected to she has to swallow hard and indicates she is reluctant to share these traumatic experiences. Later in the interview it turns out that, among other things, she had been subjected to suspension torture, that her neck was almost broken and she showed me the signs of torture on her feet and back. She quickly adds: ‘Let me simply say that ever since I have been suffering from pain in the neck caused by fused vertebrae, from rheumatism and my feet are aching. But more relevant is the political narrative, so let’s concentrate on that.’

‘There was a trial after eleven months. I was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment under the Suppression of Communism Act. During that period the BOSS7 (South African security service) tried to bribe me by asking me to work for them. After three years in prison I was banned for two years to Willowvale, in a very isolated area.’

‘Since late 1968, when I was allegedly ‘a free person’, the police have been constantly monitoring me and my house was repeatedly raided. Since then things have remained that way till December 1982 when eventually I had to go into exile.’

‘Between 1968 and 1982 I lived in the Transkei and the Ciskei. In November 1982 I was arrested with no reason given and detained for a whole week. Immediately afterward I fled to Lesotho. After my stay here in London I will probably go to Tanzania and work for the PAC. Before I left for London I was in Vienna to represent the PAC at the United Nations International Women’s Congress in support of the struggling women in Southern Africa.’

Imprisoned, tortured,banned

I have never asked myself whether or not I would continue the struggle

Do you have any family in Azania?

‘My eldest daughter (25 years old) is in Azania. I have no idea where she is or what has happened to her. She is also active in politics. My two other children (13 and 15 years old) followed me to Lesotho without any outside help. They still live there.’

Stella Moabi8, who is also present during this interview, asks how many times she has been in prison. Nomvo replies it is not just her and that it actually does not really matter, but in the end she is persuaded to answer. What follows is a heartbreaking enumeration:

- Queenstown

- East London

- Engcobo (in solitary confinement and her neck was nearly broken)

- Umtata

- Muanduli (in solitary confinement)

- Idutywa (in solitary confinement)

- Engcobo

- Kroonstad

- Pretoria Central Prison

- Nylström (Transvaal

- Umtata

Nomvo shares with us the following story about Pretoria Central Prison:

‘I shared a cell with other political prisoners. For breakfast we had porridge without a spoon and no sugar. We all asked for spoons and sugar. We were taken out of the cell and accused of rioting! The white guards refused to accept responsibility for such rebellious prisoners! For that reason we were transferred to Nylström, with a purpose-built facility as if we were hard-core criminals…’

So everything is a struggle! To move on to something else: all those years in prison, banning, raids, police harassment: what gave you the strength to go on?

‘To quit? Quitting just is not an option. My children have suffered, my people are suffering. I have never asked myself whether or not I would continue the struggle. But sometimes it was hard, though: when I was banned in 1966, I wished I was still in prison. Although I was in prison I had something to eat, however little there was, soap, a roof over my head. During my banning I had nothing: no job, no place to live, no money.’

How on earth did you manage to survive?

‘I appealed to Vorster, the then Minister of Justice, and I finally got a permit to move to a new district. A brother of mine helped me out with money and a room. I got a job on a bus. And I sewed clothes for people.’

Underground

How have you been after 1968?

‘After my banning I left the Transkei in late 1968. People from a church asked me to help women who had just been deported to, basically dumped in, the Ciskei. The church had acquired three sewing machines for the women. They asked me to organize a sewing class for them. It was a Roman Catholic church, led by white people and

attended by black people. They did a good job. I worked with the women, and successfully so, till a crisis arose at the University of Fort Hare. Clergymen were banned charged with alleged subversive activities. The church could no longer support the group and had to discontinue the activities. Then I started to set up another group with other women. I taught them how to sew so they could earn their own living. Needless to say all this had to be carried out in absolute secrecy. It involved many sacrifices and I received very little money.’

It must have been incredibly difficult for you to work with these women in those circumstances. Especially to organize them politically. Or did you find a way to overcome these obstacles?

‘Absolutely! Look, the position of these women was of course not easy: they had to live alone with their children, their husbands were working far from home in the mines. They were completely on their own: working the fields, domestic chores, raising their children. They were not in a position to earn a living with a profession. Teaching them to sew was essentially working towards the first political objective of the PAC: help people to help themselves! Of course I did not actively talk about the fact I was a PAC member. When you work covertly, it is hard to know who to trust. But look at this.’ Nomvo gets out of a trunk some pieces of cloth and dresses with printed figures in black, yellow or green: the PAC colors. Figures that represent a borderless Africa (Pan-Africanism) and, if you look closely, with the image of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, the founder of the PAC. Nomvo: ‘In this way I did political work in my sewing classes. And so I also managed to outsmart the ongoing police checks.’

You have described in a nutshell the plight of Azanian women and in particular of a politically active woman such as yourself. Is there something you would like to add?

‘The sewing classes have developed into something bigger: there is now a semi-mill with three machines for 15 women. They make table covers, clothes and print fabrics. And they are purchased through a secret address in Botswana. I took the products there myself. We should be proud of this achievement’

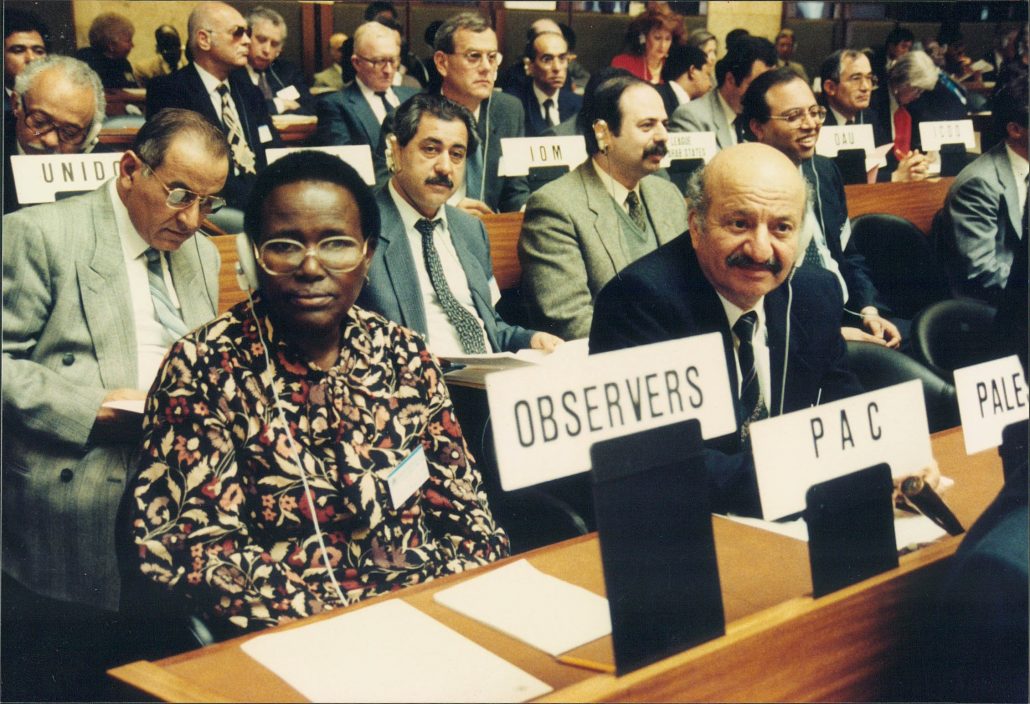

On behalf of the PAC Nomvo Booi attends a session of the UN General Assembly. The PAC had the status of observer at the UN. (Pic Mail&Guardian)

_______________________________________

© Irene Scheltes

17 August 2020

Translation into English: HippoLingo

Reproduction of articles or parts of articles is authorized, provided the source is acknowledged and that passages and quotations are not placed in a different context

Irene Scheltes about her meeting with Nomvo Booi:

Nomvo Booi 1929 – 2016

‘When I interviewed Nomvo Booi in 1983 it never occurred to me how inappropriate my too direct question was. Nomvo had to swallow and said she could not talk about the torture she had been subjected to. I felt ashamed. But Nomvo was gracious and forgiving; she brushed aside my apology and continued the interview in all openness. Out of the blue she stopped, in the middle of the interview, and showed me her back and feet. I burst into tears and I felt even more deeply ashamed. Of how she had been made to suffer. Of my thoughtlessness. Of being white and having no clue whatsoever what it meant to daily suffer under Apartheid. At that moment I felt Nomvo’s arm around me and heard her say: ‘Never mind dear. You’ve got problems of your own.’

This was over 37 years ago, but I have not forgotten this, and never will. What a top-class woman.’

Notes

[1] African National Congress, liberation movement declared unlawful by the Apartheid regime, since 1960 underground

[2] Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania, liberation movement declared unlawful by the Apartheid regime since 1960. Afterwards it operated covertly

[3] APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Army, formerly POQO) was the armed wing of the PAC

[4] The interview was published in Azania Vrij, 1983. The text has been slightly reworded. The interview was published in English in the book Women of Southern Africa, compiled by Christine N. Qunta, Allison & Busby London-New York (in association with Skotaville Publishers, Johannesburg), 1987

[5] Protests against Apartheid laws

[6] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/

[7] Bureau of State Security

[8] Then coordinator PAC Women’s Organization Great Britain