Introduction

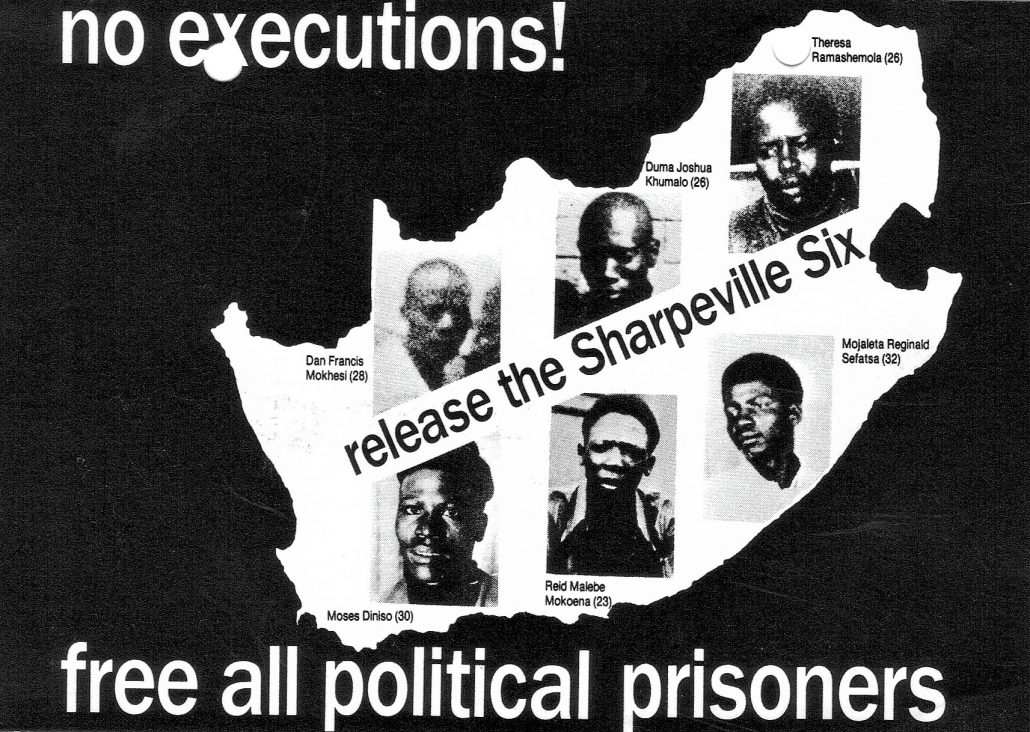

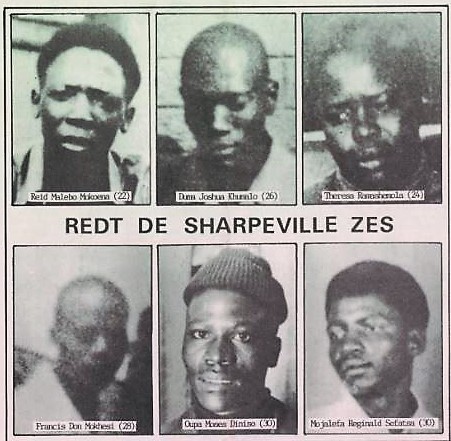

In December 1985 the South African Acting Justice Human sentenced five black men and one black woman from Sharpeville to death by hanging. Never before had a woman been sentenced to death. The Court found the Six guilty under the ‘Common Purpose’1 doctrine. That meant that the Six had been in a protest in September 1984 in which a city council member would have been deliberately murdered. Participating in a protest was sufficient to be convicted without evidence that the Six were the actual perpetrators. The Six pleaded not guilty and testified not to have committed the murder.

In 1960 Sharpeville made headlines worldwide with the brutal repression of the peaceful protest against the pass laws2. More than one generation later Sharpeville once more made the headlines worldwide. The scheduled executions of the Sharpeville Six provoked a successful national and international campaign against the death sentences. Their cause became a national and international political issue which unfolded in a context of massive black resistance against the sham reforms of the white Apartheid regime.

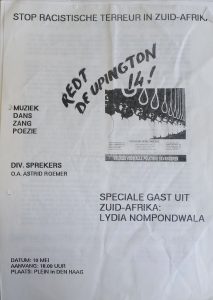

The Sharpeville Six were the first black people in South Africa whose death sentences were not carried out. In the Netherlands the Redt De Sharpeville Zes Komitee (Save the Sharpeville Six Committee)3 campaigned for the release of the Six and later also for the Upington 14 sentenced to death. In 1989 these 13 black men and one black woman from Upington were sentenced to death based on the same arguments as the Sharpeville Six.

The Sharpeville Six and the Upington 14 eventually escaped the gallows. They suffered the traumatizing effects of imprisonment, torture, being on death row and imminent executions for the rest of their lives.

Save the Sharpeville Six

The Vaal uprising 1984

The case of the Sharpeville Six and the Upington 14 took place during the period of black resistance in the 1980s. The South African regime tried to mute increasing international criticism by stepping up its image through reforms that gave the illusion of political influence and autonomy for the black majority. For the townships4 the regime introduced the Black Local Authorities Act. However, there was massive opposition among the black population.

Black Local Authorities Act

In 1982 the Black Local Authorities Act became effective. Using this Act the Apartheid regime placed local government (councils) and responsibility for the black townships with the black residents but retained control over taxes and budgets. The black council was made responsible for e.g. electricity supply, sewage, road maintenance and housing management. The regime hardly investedin thetownships so the funds for these municipal services had to come from imposing taxes and rent increases on the poor residents.

The first elections for the councils were widely boycotted. The turnout rate in the Vaal Triangle, and Sharpeville is one of the townships, was 12%. The people saw the councillors as collaborators of the regime. The black councils proposed to increase rents and communal tariffs. Evictions because of rent arrears were a widespread practice. The councillors tried to get new tenants for the vacant houses who were able to pay the rent. If they failed the councillors were dismissed by the regime or put under pressured by e.g. freezing funds.

In 1984 the council of the small township of Tumahole (near Sharpeville) increased rents with 42-53%. In July more than a 1000 people protested. The police reacted violently with teargas and arrested demonstrators. One of them was Johannes Ngake. He died while in custody. People reacted furiously and frightened councillors resigned.

Sharpeville

In Sharpeville the community, after 24 years, still felt the pain of the massacre in 1960. Joyce Mokhesi wrote: ‘The 1960 massacre had made us determined and turned us inward, away from the noisy activism of big protest. For twenty-four years the community had suffered; it had tried to forget; it had mourned; an unspeakable loss had hugged the ground like smoke from the coal fires. The world had noticed Sharpeville, but not its aftermath. It remembered the massacre, but forgot the survivors.’5

In 1984 Sharpeville once again stood up against the regime. The new generation built on what the PAC (Pan Africanist Congress)6 in 1960 and the emerging Black Consciousness Movement7 in the 1970s had started 8.

The protests against the rent increases were organized by the Sharpeville Anti-Rent Committee (SARC), later the Sharpeville Civic Association, set up by members of the Black Consciousness organization AZAPO (Azanian People’s Organization) 9. Tebogo Moselane, an Anglican priest, was one of the leaders. In the 1970s he had been active in the local branch of SASO (South African Students’ Organization) and a close friend of Steve Biko. Joyce Mokhesi, sister of one of the Sharpeville Six, remembers that in those days she and other young people from Sharpeville were taken to the burial site of the victims of the 1960 massacre by SASO-members. They cleaned the graves and listened to the poet Don Mattera 10.

The Sharpeville Civic Association maintained close contacts with black unions. Several union members were veteran members from the time of the Tsolo brothers11, in 1959, organized the workers at the company African Cables. At that time those workers were at the heart of the local PAC branch in Sharpeville12 .

Rent increases

On 3 September 1984 there was a protest in Sharpeville against the rent increases. The demonstrators were carrying cardboard signs saying Asinamali (We have no money) and We speak, you listen. The same slogans were used during the rent strikes and bus boycotts in the 1950s and in 1905 during the protests against the introduction of taxes in Natal 13‘It is a response to one of the foundation stones of white rule – the use of the tax system to impoverish blacks and force them into the white economy’ 14.

The protest turned into an uprising. The demonstrators in Sharpeville vented their fury on the local shops that exploited their monopolies to force prices up. The councillors responsible for issuing business permits had accommodated these monopolies. The demonstrators asked the councillors to join them. In case of refusal they sometimes set fire to their houses. Some councillors shot at the demonstrators from their houses. Many demonstrators were injured or killed. Also councillor Jacob Dlamini shot at the crowd which cost him his life.

Jacob Dlamini and his colleagues saw their jobs as an ‘opportunity in being the black face of white power, but not the danger’.15 Personal gain mattered more than serving public interest. Councillors used council funds for their own purposes. More than a year later the Sharpeville Six would be sentenced to death for the killing of Dlamini without any conclusive evidence. In total four councillors were killed during the Sharpeville protests and the neighbouring townships. Several councillors resigned. In the first month of the uprising the death toll was 60. At the end of that year the death toll had reached 149. In the hospitals the police arrested anyone with gunshot wounds. People were afraid of going to hospital and died at home.

The uprising with protests and strikes in the Vaal area spread to the rest of the entire country. The South African economy faced a crisis. In 1985 international banks refused to bail out South Africa and the following years saw a large-scale capital flight 16. Also the councils fell apart. In April 1985 only three of the 34 Black Local Authorities were functioning. In the five years after 1984 25,000 policemen were injured and 355 were killed 17. Several of them were killed in confrontations with APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Army), the military wing of PAC18.

State of emergency

The regime tried to suppress the uprising with violent means. In 1985 it declared a state of emergency. In 1985 the army occupied 96 townships with 35,000 men. In 1986 that number was increased to 40,000 men19 In the next 5 years 52,000 people were detained without trial. Torture was common practice. Beating up prisoners, administering electric shocks, starvation and strangulation were the preferred methods.

To break the resistance the state also mobilized right-wing vigilantes. These vigilantes20 killed people and e.g. tore down squattercamps in order to enable forced relocation. That happened e.g. in Crossroads and KTC near Cape Town. The vigilantes were often the residents of the township. Usually they were the councillors and occasionally businessmen. They had a clearer picture of the activists in the townships. In this way a picture was created of ‘black on black violence’ in the townships in order to cover up state terror. In 1986 the regime integrated the vigilantes into the police force and trained them to become ‘kitskonstables’. Later special death squads were formed that were responsible for many political murders.

The Sharpeville Six

In the months following September 1984 the police arrested the Sharpeville Six. They were charged with killing Dlamini. Who were they?

Theresa Ramashamole (24), worked as a waitress at a service area and lived with her mother Julia Moipone Ramashamole. She worked in the hospital in nearby Sebokeng. Theresa contributed to the family income, her two sisters were still studying. The eldest sister, Celestine, died in 1977 from a serious illness;

Mojalefa (Jaja) Reginald Sefatsa (30), father of a daughter, had a team of street vendors selling fruit at bus and train stations and taxi stands from early in the morning to late at night;

Reid Malebo Mokoena (23), father, was a trade unionist and worked at an engineering firm;

Oupa Moses Diniso (30), father of a son and a daughter and a building inspector at Stewarts & Lloyds, a steel company;

Duma Joshua Khumalo (26), student at the Sebokeng Teachers Training College. To finance his study and to support his family financially he sold clothing on the streets;

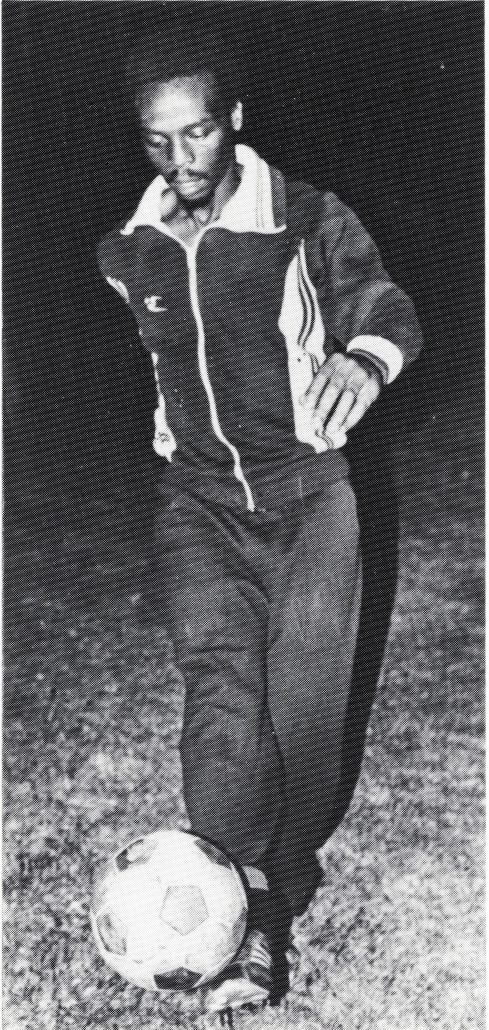

Don Francis Mokhesi (28), father of a daughter, was a professional footballer at the Vaal Professional Soccer Club worked at a supermarket. He was the brother of Joyce Mokhesi who, after the death sentences, took the initiative for international action against execution of the death sentences.

Christian Mokubung and Gideon Mokone were also on trial with the Six. They were found guilty of public violence and not guilty on the charge of murder. They were sentenced to 8 years imprisonment and served only 5.

The daily experience of life in Apartheid South Africa defined the political awareness of the Six. None of them was a member of a political organization. Duma and Francis sympathized with the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). About Theresa Joyce Mokhesi wrote: ‘Before her arrest she had been a natural anarchist. She did not need any theory, to her the system was wrong.’21

Arrest and sentence

Two months after the events in September 1984 leading up to the murder of Dlamini the first suspect of the Six was arrested. Five months later the last suspect was arrested. All were subjected to torture trying to coerce confessions. Initially Theresa was arrested to act as a state witness against the other five. She refused. Without hesitation she was arrested again on the charge of complicity in the murder of Jacob Dlamini. Most of the Six were held in custody for 11 months. It took their families more than three months to find out in which police station they were in jail and where and when to visit the Six.

Recruited state witnesses were tortured by the police so they would testify against the Six. Three years later state witness Manete wrote an open letter to Botha describing his fear of being murdered if he did not do what the police told him to. Later state witness Mongaule stated in a sworn testimony how the police threatened to throw him out of the window if he did not testify against the accused Sefatsa and Diniso.

Eventually in December 1985 the Six were found guilty of the murder of Jacob Dlamini on the basis of Common Purpose. Dlamini was murdered by multiple stab wounds. Nobody had seen the Sharpeville Six carrying weapons prior to the violence. There was no evidence that directly linked them to the murder of Dlamini. The Six maintained their innocence.

The Sharpeville Six

None of the Six and their families were prepared for the fact they would be sentenced to death. They expected a prison sentence of perhaps four or five years. In the minds of black South Africans that meant a lenient sentence. After all, people were willing to pay the price of years in prison because they refused to act as state witnesses and to betray their comrades.

Therefore the shock was unbelievably great when Acting Justice Human found them guilty and sentenced them to death by hanging. The Six and their families were facing their darkest years. Theresa’s mother was crying and walking aimlessly around in Sharpeville. She did not care where she was going or who saw her. She walked and walked: ‘if there might be news of her daughter somewhere at the end of the road’.22

In the next years the injustice they suffered would dominate Sharpeville and ultimately the international community.

The Apartheid regime used death penalties in retaliation for the uprising. At all costs the regime wanted, just as in 1960 (Sharpeville)23 and 1976 (Soweto)24, to put down this uprising. On 1 September 1987 Mnyanda Moses Jantjies and Mlamli Wellington Mielies were hanged. They were found guilty of the murder of a councillor who maintained close ties with vigilantes. At the end of that year 44 people were sentenced to death for murders related to the uprising.

Law in Apartheid South Africa

A look at the reality of the legal system in South Africa gives an idea of the context in which the trial of the Sharpeville Six was conducted.

The legal system was based on grabbed land. It served the ruling white political regime. Black people were predominantly seen as criminals and troublemakers. Not carrying your pass or e.g. not being able to pay your taxes was a criminal offence. That often resulted in a sentence to forced labour. Convicts could be employed as workers on the white farms and in the mining industry. Companies made profitable deals with the regime25.

Forced labour

A few examples. In 1903 the regime guaranteed the mining company an average of 11,000 convicted black workers who would daily work in the diamond mines. In the end De Beers stopped this line of conduct. Also road construction relied on forced labour. In 1912 20,000 convicts were employed in road construction.

Until late in the 1980s white farms were granted to employ black prisoners. They built prisons for the convicts that were working on their farms. This system was abolished under international pressure.

White legislators made laws that primarily black people could violate and did not apply to the white minority. About 40-50% of the convicted black people were convicted for criminal offences that were not illegal for white people. E.g. for violating the pass laws 17 million black offenders were arrested in the period from 1924 up to 1984.

Taking the law in one’s own hands was not at all uncommon. In the 1920s black workers were killed because they refused to greet their boss. They were shot at simply for asking for their unduly withheld pay. On white farms the black workers were often the (lethal) victims of their boss without the intervention of a judge or the police. Even after the abolition of Apartheid this still occurs.

The South African police mainly had a paramilitary role and was inadequately trained in thorough criminal investigation to solve crimes. As a result they simply searched for suspects for the convictions. In a variety of ways they tried to extract confessions. And that included torture. Even in police vans equipment was present to administer electric shocks.

On death row

Immediately following the verdict in December 1985 the Six were sent to death row. In 1986 they were given leave to appeal and in late 1987 the verdict was confirmed. In March 1988 the Six, less

than 24 hours before their scheduled hanging, were granted a stay of execution. The Six spent more than 3 years on death row awaiting their execution.

Joyce Mokhesi wrote 26 that nothing compares to the suffering of being on death row: ‘You have no energy, you have no appetite, it is torture.’ In 1988 her brother Frances wrote from death row: ‘The days were dragging very slowly. When the morning came, I wished it were night so that I could sleep. When night came, I wished it were the morning, because I couldn’t sleep at night, nor in the morning, nor during the day. I could not sleep. A minute was an hour. An hour like a day, a day like a month, a month like a year…. each day tears ran down my face at night.’

One day on death row

In the late 1980s there were about 270 people on death row. At 6 am the bell rang and the day began. One hour later the inmates must have made their beds and cleaned up their prison cells.

There were six showers and groups of 11 at a time could use them. Showering was to take no longer than 5 minutes. Next the inmates got breakfast in their prison cells. Breakfast was coffee, porridge and two sandwiches with margarine. After breakfast medication, including tranquillizers, was handed out where necessary. Then the inmates were allowed to move around or jog for no more than 30 minutes. Talking, jumping or a ball game were not allowed. Every other day the inmates were allowed to shave. After 11 am they got thin soup or juice and 5 thin slices of bread with jam. Round 3 pm they usually got rotten meat or fish with vegetables and rice.

At 8 pm the inmates had to go to bed. Lights were permanently turned on. This daily pattern changed when executions were scheduled. At 7 am the hangings took place. The others had to stay in their prison cells until the executions had taken place and the place had been cleaned up.

Inmates could not work, were forced to doing nothing. Some only stayed in their prison cells of not more than 2 by 3 metres. Others shared a prison cell with no more than 8 persons. Most of the day they were locked up. After 1989 the inmates could occasionally watch a video.

Visitors

Those condemned to death could see visitors twice a day. A daily visit was a problem for the family; for the inmates something to look forward to. Because of traveling time, costs and daily routines relatives were not always in a position to visit. The inmates found that difficult to understand. ‘Pain and despair rob people of reason.27’ They lived from visit to visit and imagined what the visit would be like. ‘Like young lovers, their perception was sensitive to the smallest wavering of action. They were men with wives and families; yet were unable to protect, unable to defend, no better than boys with only dreams to offer.28’

The hanging

Each time seven people could be hanged simultaneously. The last seven days before the hanging people were housed in a special cell block. That cell block was called the ‘pot’ because there the level of stress reaches boiling point. On the day of execution the prisoners on death row attended a short church service. With hands tied behind their backs29 a white pillowcase was pulled over their heads. And then the noose of the gallow was fitted around their necks. In this way they waited for the trapdoor to open.

Afterwards relatives of the hanged men could go to the closed coffins. The bodies remained permanently in state ownership.

After the executions the prison wardens took the ropes and pillowcases to the showers to wash off the blood and vomit, ready for being used again.

Stay of execution

On Monday 14 March 1988 the Six had to get their belongings and were taken to the ‘pot’. On Friday 18 March their execution was scheduled. They had to undress, were weighed and the circumference of the neck was measured. The heavier the person the shorter the rope. In that way the force of the drop is sufficient to break the neck and sever the spine30.

Of the Six Sefatsa was in the prison cell closest to the ‘pot’. In the last few years he had heard the condemned men in their final hours, their crying, their mood fluctuations from bravado to childlike helpnessness and the futile pounding on the cell doors.

Francis Mokhesi and Theresa Ramashamole were Catholics and two days before the scheduled execution they were visited by the priest from Sharpeville and the Archbishop of Pretoria. The other four (Protestants) were not visited by them. The Sharpeville Six were sentenced as a group, the community supported them as a group, people campaigned for them as a group. These representatives of the Catholic Church thought otherwise31.

Less than 24 hours before their scheduled execution the Six were informed the execution was stayed. The by now worldwide campaign against the death sentences of the Sharpeville Six had saved their lives for the time being.

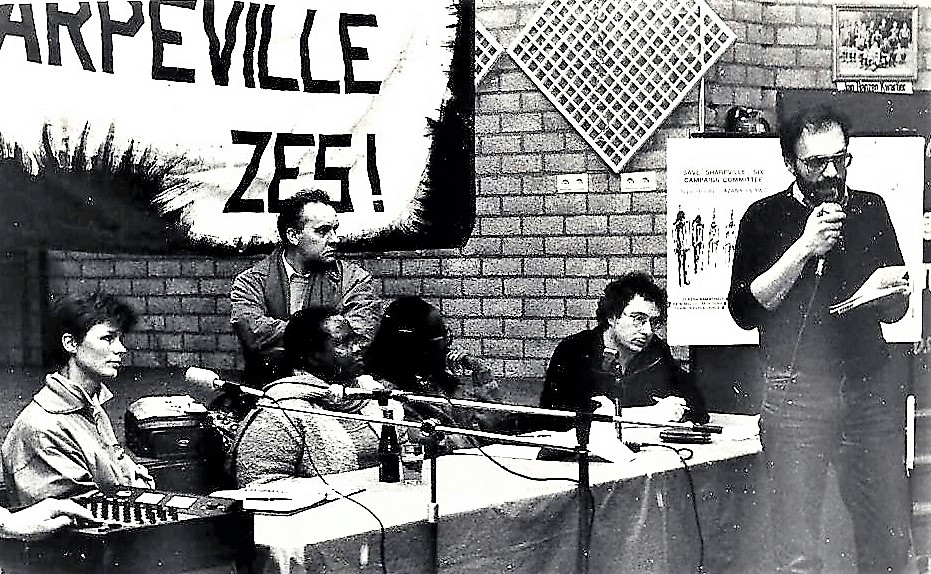

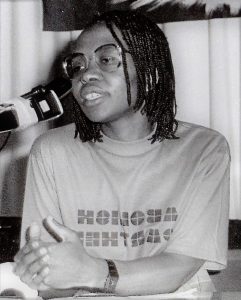

Meeting in Amsterdam with Marjan Boelsma, Julia Ramashamole, journalist Bert Bakker, Joyce Mokhesi, Charles Braam (Cineclub), Farouk Asvat reading his poetry.

Campaign Save the Sharpeville Six

1985

Start

After the death sentence of the Six late 1985 Joyce Mokhesi, sister of Francis Mokhesi, decided to launch a campaign to save them from the death penalty. Joyce herself had been arrested four times before. She carried the scars on her skin of the electric shocks and burning cigarettes32.

At the time of the death sentences Joyce was studying in England33. She contacted several student organizations and the then Labour Party leader, Neil Kinnock, to take action to avert executions of the death sentences. In her book she outlined what happened. Individually the students sympathized with the campaign but their organizations were related to the ANC (African National Congress). The Six were no ANC members nor members of any other political organization. Joyce insisted on that political independence so they could not be claimed by anyone and the right be claimed to speak on their behalf. The ANC and the affiliated organizations and sympathizers were rather annoyed. Solly Smith, then ANC representative in London, made it clearly understood that if he could not run the campaign he would block her efforts for action in the United Kingdom. Joyce refused. Student organizations confirmed they could only join when instructed to that end by the ANC. It never got to that point. The ANC did not join the campaign until the Sharpeville Six had become world news. The office of Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock informed her they sympathized but that Kinnock could not be involved personally. However, some conservative MPs did support the campaign.

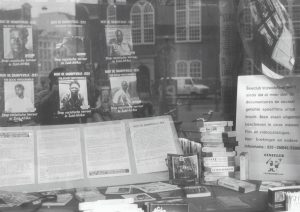

City Centre of Amsterdam bookshop Atheneum

Committee Save the Sharpeville Six

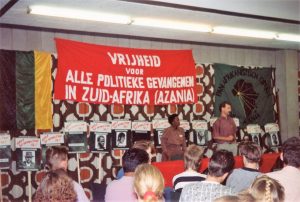

In June 1986 Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms and the Azania Komitee set up the Komitee Redt De Sharpeville Zes (Save the Sharpeville Six) to campaign against the death sentences and for the release of the Sharpeville Six. The Committee also stood up fo the release of all political prisoners in South Africa. Among them: Zephania Mothopeng (PAC) and those sentenced to life: Nelson Mandela (ANC), Jafta Masemola (PAC), Walter Sisulu (ANC) and John Nkosi (PAC). Jafta Masemola was the longest serving political prisoner on Robben Island. With the slogan Viva Azania , Boycott South Africa the the Committee supported the demand of a total boycott of the Apartheid regime and appealed for support for all resistance and liberation movements such as the PAC, ANC, AZAPO, BCMA, UDF, NF34 in Azania/South Africa.

1986

Actions

The Committee worked closely together with Joyce Mokhesi. In 1986 she visited the Netherlands and in June she spoke at the Soweto Commemorations in Rotterdam and Amsterdam. The focus of these commemorations was the campaign for the Sharpeville Six35.

Joyce: ‘The facts suggest that the regime in Pretoria was not interested in justice, never even as written in its own unjust laws. Therefore it is true that the Sharpeville Six are the victims of a political decision. The regime seeks to punish black people for the fact they refuse to recognize the councils, which do the dirty work. The regime seeks to punish and intimidate the people for challenging the authorities. The Six were either arbitrarily arrested or carefully selected to serve as an example for the rest. But intimidation does not work in a revolutionary situation. It only helps to increase violence and the number of revolutionaries. The problem in South Africa is not the black people, it is the Apartheid system itself36 .’

The other speakers, Johnson Mlambo, then Chairman of the PAC, Thabo Mkhabane, representing the BCM in exile and Roy Wijks of SAWO (Surinamese Labourers and Workers Organization) supported the campaign.

On 10 June, at the initiative of the Sharpeville Six Committee, political and social organizations presented a petition to the Dutch government requesting to vigorously protest against the death sentences37.

On 26 June 1986 the Ministers of Foreign Affairs met in The Hague for an EEC Summit. The Committee formed a picket line and asked the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Van den Broek, to put the case of the Sharpeville Six on the agenda. He decided to raise the issue not until the death sentences would be confirmed on appeal. The Netherlands continued to have confidence in the judicial process in Apartheid South Africa….

Cineclub, in partnership with the Azania Komitee, released the film Izwe Lethu, the country is ours. The film shows an interview with PAC leader and ex-Robben Island prisoner Johnson Mlambo about the situation in South Africa/Azania and a call for solidarity with the Six. In Amsterdam the movie could be seen on cable TV in the Vrijheidsjournaal.

In October 1986 on the International Day of Political Prisoners the Committee organized a protest in Amsterdam. A signature campaign was to put pressure on the Dutch government to make every effort to prevent the execution of the death sentences. Everyone was called upon to fight for the lives of the Six condemned to death. In December the Committee organized in five branches of the Amsterdam Public Library an exhibition about the Sharpeville Six with signature-collecting sheets. The Committee also urged people to send letters to the Six in Pretoria Maximum Prison.

Meeting in Amsterdam with political exiles from the BCM

On Human Rights Day, 10 December the Committee presented the 2899 signatures up to that date38 to the Director Africa and Middle East at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He informed us that the Minister would not condemn the verdict until the death sentences were final. The Six had been on death row by then for one year waiting for their appeal. On 6 January 1987 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs informed us that the course of the trial would be closely monitored by the embassy in Pretoria.

1987

Confirmation death sentences

In December 1987 the death sentences were confirmed on appeal even though it was acknowledged that none of the Six could be directly linked to the death of Dlamini. In the week before Christmas it was rumoured that the Six would be hanged shortly. The Security Council of the United Nations was convened at the request of the African countries and appealed to the Botha regime to reconsider the verdict. The Sharpeville Six Committee started an international card campaign addressed to Botha requesting not to carry out the death sentences.

In a letter to the Committee Regina Sefatsa (Reginald’s wife) wrote: ‘I am writing heartbroken, but still hoping that until the last minute something will happen. You and your friends still continue to support us. I am asking you to put pressure on the South African government to change the verdict.’

The Committee sent a telegram to the families of the Six vowing to continue the actions. On the Dam in Amsterdam the Anti-Apartheidmovement, led by Bart Luirink, organized a Christmas Vigil for the Six. He would not let a spokesperson of the Committee read out loud Regina Sefatsa’s letter. His argument: there was already a choir, there were speakers etc. On a previous occasion the Anti-Apartheidmovement, which exclusively supported the ANC, refused to join a campaign for the Six because they were no ANC members. The Anti-Apartheidmovement did not take action until the case for the Six generated much publicity and gained international support.

The Special Committee against Apartheid of the UN and the OAU (Organization for African Unity) called upon the international community to condemn the death sentences. Also the United States under Reagan appealed to the regime.

Support in Azania for the Six

Since the uprising many families in Sharpeville and the Vaal area had suffered from the brutal repression. Parents whose children had been killed, children who had lost their parents and people detained and tortured without trial. All this also meant loss of income and even greater poverty. These victims, just like the Six, also paid for the Vaal uprising. The Six also represented them. Joyce Mokhesi: ‘The Six, it was felt, were being killed not for what they had done, but for what they represented. The white challenge was accepted. The judgement became a focus for rage, and from then on one began to hear it said that the Six would not die alone.’

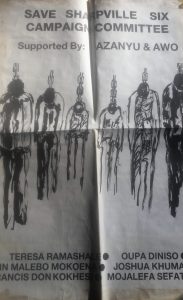

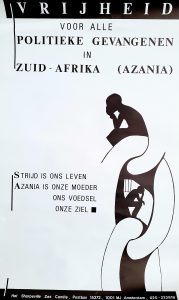

Poster

In South Africa AZAPO, UDF, SABMAWU (South African Municipal Workers Union), AZANYU (Azanian National Youth Unity), AWO (African Women’s Organization), COSATU (Congress of South African Trade Unions) and NACTU (National Council of Trade Unions) organized actions against the death sentences and support for the families of the Six. The actions met with considerable opposition from the South African regime. E.g. the publication of Save the Sharpeville Six by NACTU was banned. A number of people who were collecting signatures for the case of the Six were arrested. It did not stop the support. Petitions were written. T-shirts were printed. All over the country the news spread. Joyce Mokhesi wrote: ‘Azania itself began to stir’39. People realized you could be hanged without evidence you had actually murdered someone, but only participated in a protest in which someone was murdered.

The South African regime remained uncompromising. It was accustomed to years of international criticism, criticism of South African liberals and black resistance. Protests from within and internal division might bring about a change. Based on this consideration Joyce Mokhesi contacted IDASA (Institute for Democratic Alternatives in South Africa), an Afrikaner think tank led by Frederick van Zyl Slabbert.

IDASA was in contact with student groups at the universities of Stellenbosch and Potschefstroom, bastions of Afrikanerdom, which could possibly make Botha reconsider his decision. Several students organized rallies and wrote petitions to save the lives of the Six40. A white mechanic, Tony Viljoen, wanted to start a signature campaign for humanitarian reasons and present the signatures personally to Botha.

Shocking was the position of Helen Suzman, the white liberal MP in South Africa. She asked the regime not to carry out the death sentence but added: ‘Finally, I want to say that these people will not go unpunished- they will not go unpunished- they will of course go to prison for life41 .’

1988

Imminent execution

After the death sentence Joyce Mokhesi frantically traveled the world to obtain political support for the case of the Six. Julia Ramashamole, mother of Theresa, joined her. Both were then the only family members with a passport and so the only persons who could travel.

They met with the Special UN Committee against Apartheid, several American politicians and with Chester Crocker (Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs) of the Reagan administration. Initially the meeting would take 30 minutes. He was so interested in the case that in the end the meeting lasted 2 hours. In London Thatcher refused to meet Joyce and Julia in person. They only saw her Private Secretary.

On Monday 14 March the Six were informed they would be hanged on 18 March. It was uncommon that convicts were informed of the date of their execution at such short notice. It was an attempt to to buy time so that the rest of the world would know only shortly before the execution. Another political prisoner on death row, Robert Mc Bride42, heard about the execution date and told it to his girlfriend Paula Leyden who was visiting him. Paula was a highly experienced activist and immediately informed embassies, press and lawyers43.

The days that followed 15 March were hectic. Chester Crocker personally called Pik Botha, the South African Minister of Foreign Affairs, to underline the appeal of the Reagan administration. Cardinal Hume, head of the Catholic Church in Engeland and Wales, the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury and the Pope urged Botha to grant clemency.

Amnesty International supported the case. That was significant so people could be convinced that the inconceivable was real, that the South African Supreme Court was planning to hang people for a murder they had not committed.

The English Anti-Apartheid movement organized a press conference with Labour leader Neil Kinnock and Shridath Rampal, Secretary-General of the Commonwealth. President of the Federal Republic of Germany, Von Weizsäcker, asked for a pardon for the Six during his visit to Zimbabwe. The American President Reagan personally asked Botha for a pardon.

Julia and Joyce returned to Sharpeville for their last visit to the Six. The situation was tense in Sharpeville. The roads of the townships were closed. Security forces were patrolling the townships. A witness to the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 said this about the bitter mood among people. ‘The hearts of the people of Sharpeville are bleeding. It is even worse than 196044.’ White residents from nearby Vereeniging were, for selfish reasons, openly critical of Botha’s stubbornness. : ‘It’s easy for him. He is secure and comfortable wherever he is. We are the ones who are going to feel the anger and bitterness because we live and work near you. We know how you black feel about this matter. If these people are executed and there is a riot, we are the ones who become victims.’

The Hague 1988 with Karel de Waal (1948-2011) vice-chair of the Azania Komitee

The Committee Save the Sharpeville Six organized on the evening before the scheduled executions on 18 March 1988 a protest in front of the South African embassy in The Hague. On the same day there was the news there was a stay of the executions for legal reasons. The protest continued with joy and a fighting spirit. After all a stay did not mean a reprieve. At the protest Maarten van Traa spoke on behalf of the PvdA (Labour Party) and Jan Ter Laak on behalf of Pax Christi.

In front of South African Embassy in The Hague. Joy after the news of the stay of execution

Poster

Acting Justice Human dismissed a reopening of the trial. Again the countdown started. In July execution was imminent and again under pressure of the international community a stay was obtained. The Six stated in a letter to Botha they were not asking for mercy but merely for justice. They kept hoping because of the overwhelming support from all over the world. They received mailbags filled with statements of support from across the world. For the first time in years the death penalty in South Africa was a political issue again.

International support

Joyce Mokhesi and Julia Ramashamole

In 1988 Joyce Mokhesi and Julia Ramashamole visited the Netherlands twice. The Committee Save the Sharpeville Six introduced them to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the press, politicians, social organizations and organized several meetings with them.

Worldwide the Committee sent about 20,000 protest cards. In 1988 Joyce and Julia visited the Jeroen Bosch College in Den Bosch, which also collected signatures at other schools in the area. They attended a church service in the University Church in Eindhoven which also took action for the Six. They addressed the FNV (Federation of Dutch Trade Unions) women’s conference on its South Africa event for union activists. Amnesty organized a meeting with them and they joined an Anti-Apartheid cruise through the harbour of Rotterdam.

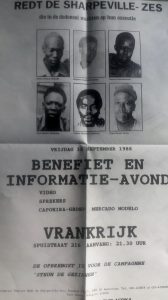

In Amsterdam the squat bars Vrankrijk and Van Hall organized fundraising concerts for the families of the Six.

Poster fundraiser Sharpeville Six

On another visit Joyce was accompanied by Mamolise, daughter of her brother Francis. On their travels Julia, Joyce and Mamolise succeeded in getting the case of the Six on the international agenda and so ultimately in saving their lives.

The months after the imminent execution in March the protests continued. In Paris e.g. more than 12,000 people were mobilized heading for the Bastille. In Cape Town a protest of youngsters was dispersed with tear gas.

Botha with his back against the wall

After the first stay of the executions Julie and Joyce again toured the whole of Europe. The German Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Kohl government, Genscher, received Julia and Joyce. Thatcher was the only conservative leader trying not to get involved. Still she did not want to be the only person to support the Botha regime. The ambassador asked Botha ‘to exercise the prerogative of mercy45 ‘.

The next execution date was scheduled in July. Joyce and Julie met the Foreign Affairs Ministers of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, West-Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. They also met Daniëlle Mitterand, wife of the French President. Later Joyce would still meet Mitterand in person.

The South African ambassador was called to account by the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs. West-Germany indicated it was considering sanctions if the executions were performed. On the summit of European Ministers of Foreign Affairs on the EU budget and subsidies for farmers it was urged ‘that all legal options available in South Africa be used to prevent the death penalty from being carried out’46.

The European Heads of Government issued an urgent request for clemency for the Six. If not granted that would seriously damage relations with South Africa. Behind the scenes sanctions were being planned. A list of sanctions was put together that would be imposed if South Africa continued with the executions. The list included a boycott of South African coal and withdrawal of landing rights for the South African airline47. Chancellor Kohl of West-Germany abandoned his opposition. Before he had supported the British government that was against imposing sanctions. The British government was the only Western country to continue to oppose sanctions.

On 5 July West-Germany publicly stated the South African government could expect a sharp reaction if the Six were be hanged. For the remaining political friends of the South African regime it became more problematic to still oppose sanctions if the Six were hanged for a murder they had not committed.

Meeting with Thatcher

Time was running out and Botha did not give in. Thatcher was the only conservative Head of Government left who continued to protect Botha by not threatening with sanctions. Joyce Mokhesi again asked for a meeting with Thatcher.

On 12 July Thatcher received her at Downing Street. From the transcript48 of the conversation: ‘She (Joyce Mokhesi) hoped that the Prime Minister could make clear to President Botha that she felt as passionately about her appeal for clemency as she did about her opposition to economic sanctions. Otherwise there might be a risk that President Botha would think that Britain was half-hearted.’ Thatcher replied Botha would not come to that conclusion. ‘The Prime Minister said that she would ensure that President Botha knew the strength of her views on this case. The fact that she was known to be a supporter of capital punishment might give her request for clemency greater weight49.’ Thatcher was convinced that in the exceptional case of the Sharpeville Six the death penalty was not justified.

Joyce about her meeting with Thatcher: ‘Whatever her motives, however, I shall always be grateful that she agreed to see me, and that when she did, she treated me directly without any condescension, without that assumption I often find in England that because I am African, therefore I must be stupid and ignorant. There was none of that subtle racism in her50.’ Thatcher was thoroughly informed of the case. At the end of the meeting Thatcher said her door would always be open for Joyce. Joyce clung to these words and was convinced she would help. The South African regime had run out of powerful defenders.

Julia Ramashamole and Macteld Cairo (Surinam Women’s Collective) at a meeting in Rotterdam.

Amsterdam with Bella Zurcher and Marianne Hond (Sharpeville Zes Komitee)

Europe, US

In Europe Joyce spoke with Jacques Delors51, President of the European Commission and with Cardinal Etchegaray of the Vatican human rights organization: the Pontificial Council of Justice and Peace. They all expressed their support to prevent the death sentences from being carried out. Joined by Mamolise Joyce traveled on to the United States and there she met congresspersons and senators. They received expressions of support from ex-President Carter, Vice President George Bush and the Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis. At that time Dukakis was ahead in the polls and threatened, once elected, to declare South Africa a terrorist state.

Charta 77

The Czechoslovak civil rights movement Charta 77 also expressed its support for the Sharpeville Six. In a statement they joined the ‘worldwide appeal: save the lives of the six young people from Sharpeville. Stop the execution and grant them clemency. This international appeal is driven by respect for human life and human rights as well as by our sacrifice in this part of the world’. The appeal was signed by the prominent dissidents: Jaroslav Sabata, until the Warsaw Pact invasion in 1968 Secretary of the Communist Party in the province of Moravia; Jiri Hajek, till the invasion Minister of Foreign Affairs; Jiri Dienstbier, journalist and former correspondent of the national public press agency CTK in the US and the Far East; Peter Uhl, an engineer and arrested several times for political activities. Herbart Ruitenberg of the foundation Stichting tot Steun aan Demokratische Krachten (Support Democratic Forces) had informed them about the plight of the Six.

Once more stay of execution

In June and July 1988 the executions were stayed again.

The Six were dissatisfied with their lawyer Prakash Diar. They frequently complained about broken promises and not receiving in time the correct documents. Joyce suggested several times to get a new lawyer but initially they did not react. Their stay on death row took its toll. Joyce Mokhesi: ‘It took me time to understand that this silence was the expression of their pain, that they had reached the point where sacking Prakash had become unthinkable. Death row had made them too fragile to bear the confusions of uncertainty (..) They had learnt how to suffer but had lost the confidence to make decisions and the skill of acting on them52.’

In August 1988 Sydney Kentridge joined the defense. He had led the investigation on the death of Steve Biko, was involved in the defense in the Treason Trial in 195653 and investigations into the Sharpeville massacre in 1960. He was one of the few white people who were completely trusted and who was in a position ‘to defend us from the system and its law’54.

They appealed to the refusal of the Court to reopen the trial. The trial was in September. On 23 November 1988 the appeal was dismissed again. The legal instruments to save the Six from the death penalty had been exhausted. Now it was up to Botha to move.

Death sentence commuted

That day the Six were led to believe for hours they would be hanged. Not until later that day was it reported Botha had granted the Six clemency. The death sentence was commuted to prison sentences ranging from 18 to 25 years. The Six left death row and were transferred to the high security section of Pretoria Central Prison.

Videoclip with impression of protest in Amsterdam and The Hague.

Death penalty Upington 14/26

In 1988 26 people in Upington were found guilty of murder. The trial took 18 months. It was the largest group ever to be found guilty of a murder. The trial started in 1986 behind closed doors because a number of the defendants were under age. The 26 were alleged to have been involved in the death of a policeman during a protest in 1986. The judge found them guilty on the same controversial principle of common purpose as the Sharpeville Six. In his sentence the judge admitted that most of them had not actually been involved in the murder.

How it began

There was enormous poverty in Paballelo, the township near Upington. Unemployment rate was with 31% higher than the national average of 18%. Virtually no one earned more than 250 Rand. Many had to make do with an income of 150 Rand (now roughly 75 Euro). The rent had become unaffordable. What provoked outrage was that the mayor of Paballelo did not have to pay his rent arrears whereas others were evicted from their houses because of rent arrears.

In 1985 youngsters took the political initiative by forming the Paballelo Youth Organisation (PYO). School boycotts against poor education were organized. Initially there was a gap between the elderly and youngsters because of misconduct by some of them. The PYO succeeded in bridging that gap. The PYO promoted more discipline and launched a campaign against alcohol abuse among young people.

A son of Evelina de Bruin, later sentenced to death, and her husband Gideon Madlongolwane, was a teacher at a local high school. He was fired because of his political commitment.

In 1985 people gathered in protest at the local football field to discuss the hight rents. A few days earlier the police had already killed four people. The police dispersed the crowd of 3,000 with teargas. After that people gathered again outside the house of police officer Lucas Sethwala. He opened fire, shot a protestor and tried to flee. He was caught and kicked to death. The Upington 26 were found guilty of that. They pleaded not guilty.

1989

Death penalty

In May 1989 14 (including 1 woman) of the 26 defendants were sentenced to death. They ranged in age from 24 to 64 years. The other 12 defendants received sentences varying from community service/hard labour to 8 years imprisonment. On the day of the verdict they had been held in custody for nearly 4 years.

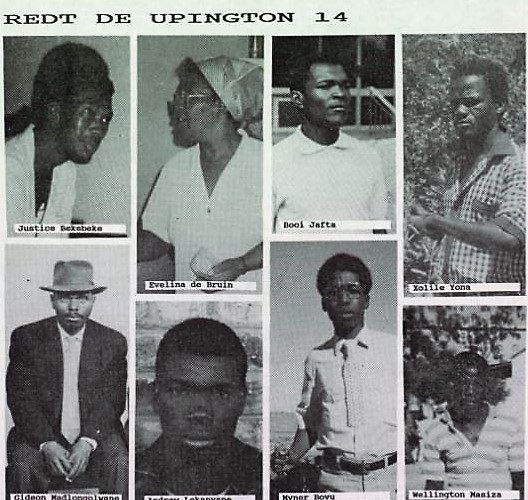

The Upington 14

The 14 people who are in danger of being hanged:

Kenneth Khumalo (1956), treasurer of the city council of Paballelo and father of three children;

Tros Gubula (1959), worked in Upington and father of one child;

David Lekhanyane (1964), a Kimberley high school senior;

Myner Gudlani Bovi (1960), internship supervisor in Fort Beaufort, father of one child;

Zuko Xabendlini (1957), mailman at a construction company and father of one child;

Andrew Lekhanyane (1960), elder brother of fellow convict David Lekhanyane. Worked in Upington at an electricity company and has one child. During the trial Andrew’s and David’s mother passed away;

Justice Bekebeke (1966), a paramedic in Windhoek, Namibia and father of two children;

Zonga Mokgatle (1958), unemployed and father of four children;

Wellington Mazisa (1962), father of three children and working at a construction company;

Booi Japhta (1965), unemployed;

Evelina de Bruin, date of birth unknown, about 63 years old. Mother of ten children, two grandchildren. A domestic employee in a white family and illiterate. She had a heart condition, high blood pressure and she was a rheumatic patient. Evelina is the wife of co-defendant Gideon Madlongolwane;

Gideon Madlongolwane, about 60 years old and a long-term employee at the railway company. He was a board member of the Pabalello Chiefs Soccer Club. Two of his sons, Cedric and Welcome, both teachers, were in prison during the state of emergency in 1988;

Xolile Yona (1964), professional fighter and father of one child. Doctors testified that he was psychologically unfit to stand trial. The Court did not pay any attention to that;

Albert Tywilli (1962), worked for the police and father of two children.

Justice Bekebeke, one of the 14, said about his stay on death row: ‘The prison itself was a death factory; its creators created it with the intention to kill… You sit there thinking about what happens at the point of death, the thereafter, your family, loved ones, children and girlfriend. That’s the pain55.’

The lawyers Andrea Durbach and Anton Lubowski conducted the defense. In his hometown Windhoek in Namibia Lubowski56 was assassinated in September 1989 by a death squad of the South African regime.

Campaign Save the Upington 14

The South African Council of Churches, NACTU and the Cape Action League (CAL) launched a campaign for the Upington case. Joyce Mokhesi was also committed to saving the lives of the Upington 14. The Committee Save the Sharpeville Six called attention to this case in the Netherlands and started a letter and card campaign. The Upington 14 had to know they were not alone.

Ds. Aubrey Beukes, who felt committed to the Upington defendants, informed the Committee. Beukes had been imprisoned for three months at the time of the protests in 1985. After he had conducted a prayer service for the 14 with more than 1000 people present his church was vandalized and his car damaged. Flyers slandering him were distributed. A member of the ultra-right white organization Wit Wolwe (White Wolves) threatened to kill him.

Evelina de Bruin’s medical condition seriously deteriorated. With a special campaign they tried to get her out of prison before Christmas 1989. In the Netherlands the Committee organized a vigil near the South African embassy together with the Hague-based Werkgroep Zuidelijk Afrika (Committee Southern Africa), Cineclub and the Azania Komitee. The foreign affairs specialist of the Partij van de Arbeid (Labour Party), Josephine Verspaget, addressed the audience. Because of the international support Evelina de Bruin’s conditions were improved. Occasionally she could see her children and hang pictures of them in her prison cell. But still she could not leave prison.

In Paballelo Mayibyu, an organization which mobilizes employed and unemployed youngsters supports the Upington case. The organization is closely related to SOYA (Students of Young Azania). They were fundamentally anti-sexist, anti-racist and non-sectarian. This non-sectarianism emphasized the importance of joining forces in the Upington case. They had to pay for their support to the protest in 1985 and to the case of the Upington 14 with arrests and torture. A number of them were restricted in their freedom of movement.

1990

Visit from Upington

In 1990 Lydia Nompondwana visited the Netherlands at the invitation of the Committee Save the Sharpeville Six. She was treasurer of the support committee of the Upington 14 in South Africa. Her husband Enoch Nompondwana, one of the Upington 26, was serving a sentence of 8 years.

Lydia Nompondwane with Mayor of Amsterdam, Van Thijn

Lydia met with Dutch MPs and visited the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. She was given the assurance that a representative of the Dutch embassy in South Africa would visit the people on death row and would monitor the appeal. In Amsterdam, The Hague and Nijmegen Lydia was received at the city hall.

The mayors Van Thijn (Amsterdam) and Havermans (The Hague) promised support to the co-operative projects in Paballelo to fight poverty and unemployment.

Poster for rally in The Hague

Meetings with Lydia were organized in Nijmegen with the Sihambile Cultural Group, in The Hague with the Committee Southern Africa. The meeting in Amsterdam was also attended by Itumeleng Mosala, AZAPO leader.

The principle of Common Purpose on which the death penalties were based intimidated the people, Lydia said and ‘it is a political case, because our people raise their voices against oppression. People are scared, do not attend gatherings for fear of becoming victims of the common purpose doctrine’.

In 1990 the regime released Mandela and other political prisoners. The liberation movements ANC and PAC, banned since 1960, could take action again in public. Lydia: ‘The day (11 February 1990) Mandela was released we celebrated. We anticipated a speedy release of our people. My mother-in-law was in my house waiting for her son. But now the people are frustrated. There is nothing to hope for. The regime continues to treat them as criminals instead of as political prisoners.’ Actions demanding the release of the Upington 14 and the Sharpeville Six were still relevant.

Jeroen Bosch College

The students at the Jeroen Bosch College in Den Bosch campaigned, inspired by a visit of Joyce Mokhesi to their school, for the Sharpeville Zes and later also campaigned for the Upington 14. Student Monika Roeling was one of the driving forces. Invited by students and teachers Lydia Nompondwana gave two lectures at the College. Lydia thanked the students for sending 500 greetings to the Upington 14. She referred in particular to Evelina de Bruin who was on the mend with the help of international support.

Lydia Nompondwana at the Jeroen Bosch College in Den Bosch

A year later the students of the Jeroen Bosch College clogged up the fax machine of the South African embassy for a couple of hours with a message for President De Klerk 57 :‘Be honest. You promised. Release all political prisoners now.’

1991

First releases Sharpeville Six

Upington 14 saved

Oupa Diniso

In 1991 on 10 July Diniso and Khumalo were the first of the Six to be released. They arrived in the evening in a dark Sharpeville. People were disconnected from power because of unpaid bills.

Diniso expressed his concern about the Western countries who are more than willing to be deluded by the mainly cosmetic changes in South Africa. ‘I still have no right to vote and still political prisoners are held in detention. What bothers me is that 2 police officers, Legrange and Van der Merwe, have been released as well. They are not political prisoners. They had been sentenced for murder to 25 and 15 years. They were no ‘first offenders’.’

In a letter to the Committee Khumalo writes: ‘The only thing I wish to do is to salute you for the part you played in our suffering. Words cannot express my feelings of joy, even though our suffering is not over yet.’ In addition he asked us to continue our efforts for the release of the remaining Sharpeville Six. He pointed out the severe financial problems of the families of the Six. He ends with an appeal for financial support. After a previous appeal by Julia Ramashamole the Committee had already made a start. The funds raised were not more than a drop in the ocean.

In December 1991 Reid Mokoena and Theresa Ramashamole were released. For the Committee Marjan Boelsma visited Theresa in prison shortly before her release. Theresa had been transferred from Pretoria Central Prison to Diepkloof Prison in Soweto. There she could touch and embrace her visitors, something that was denied her for six years. She thanked the Committee for the efforts that saved her life and the lives of the others. Her mother Julia had already told her that the Committee continued its actions for the release of all Six.

Death penalties Upington 14 commuted to prison sentences

On 28 May the Court commuted on appeal the death penalties of the Upington 14 to prison sentences, ranging from 2 to 12 years. Most of the Upington 26, which included the 14 on death row, were released. Five members remained imprisoned. The death penalties of Justice Bekebeke and Zolile Yona were commuted to 10 years imprisonment. The death penalty of Zonga Mokgatle was commuted to 12 years. The prison sentence of Enoch Nompondwane, Lydia’s husband, remained 8 years as well as for Elijah Matshoba.

Poster Sharpeville Zes Komitee

On 15 June the Paballelo residents demanded in a protest march the release of the five remaining Upington 26 in prison. At the rally a fax was read from the Committee Save the Sharpeville Six, Cineclub and the Azania Komitee vowing the campaign for the release of all political prisoners would be continued.

On 12 September 1991, anniversary of Steve Biko’s death, the Committee organized a picket in front of the South African embassy campaigning for the release of all political prisoners. An estimated number of 1500 political prisoners were still in detention. Of the Sharpeville Six and the Upington 26 still nine were in prison. In an action with pre-printed cards addressed to President De Klerk the release of all political prisoners was demanded in six languages. In a letter to Minister Van den Broek of Foreign Affairs organizations58 urged him to raise the case of the Upington 14 and Sharpeville Six in the European Community. The Dutch government was urged to call on the South African regime to release all condemned.

In front of the South African Embassy in The Hague

1992

All released

Early 1992 the Upington 26 were all released and also Reginald Sefatsa and Francis Mokhesi of the Sharpeville Six were released later that year. The ANC worked out an amnesty with the regime. The amnesty also covered racist killers such as Barend Strydom who killed eight black people. The Upington 26/14 and the Sharpeville Six were not done justice. They had been on death row for years, innocently.

Neville Witbooi in Dordrecht, the Netherlands

In 1993 Neville Witbooi (25) took a course in Dordrecht organized by Lagere Overheden Tegen Apartheid (Local Authorities against Apartheid) and the Vereniging van Nederlandse Gemeenten (Association of Netherlands Municipalities). Witbooi was one of the condemned Upington 26. At the time of his trial he was under age and was sentenced to forced labour in a retirement home. Witbooi was chairman of the Paballelo Civic organization. Now he was unemployed and a volunteer at the Civic. On behalf of the Upington 26 Witbooi thanked the Committee and everyone who had fought for the Upington 26.

Sharpeville Six

Francis Mokhesi sent a letter of thanks to the Committee Save the Sharpeville Six. The Six returned to an impoverished Sharpeville. Theresa was working at the ANC women’s organization. The others were unemployed and with no income. Julia was a member of a union for health-care workers and municipal workers (FEDMAWU – Federation of Municipality and Allied Workers Union)59. Phillip Dhlamini, leader of the union, supported the Six wherever possible. They tried to start a joint fish-and-chip shop and a joint sewing project for women.

The Six and their families were grateful for the strong support they had received from at home and abroad. For a while they were invited to another church in the Vaal area every Sunday so as to thank the people personally. Regina Sefatsa wrote: ‘I would like to thank all the people abroad, in particular the Sharpeville Six Committee. I am what I am because of your support.’ The Committee passed on these thanks to all, ranging from social and church organizations, political parties, schools, action and solidarity groups to individuals, who have fought for the lives and the release of the Six.

When the Six were still in prison their lawyer Prakesh Diar left for Canada, taking with him their files and leaving no address. They never received a single cent of the promised profits of the book60 he wrote about the case. In the end the Six were given amnesty by the TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission), but they were not compensated for their ordeal in prison. Their case has never been reopened nor their names cleared.

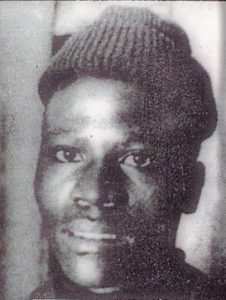

Francis Mokhesi

Present situation?

The Sharpeville Six

Of the Six only Reginald Sefatsa and Reid Mokoena are still alive. Sefatsa is selling fruit again near the taxi stand like he used to do before his arrest. Reid Mokoena works as a cleaner for the district municipality in Sedibeng.

Theresa Ramashamole was suffering from health issues. A leg was amputated and she ended up in a wheelchair. Till her death in 2015 at the age of 56 she had been working as an ANC councillor.

Oupa Diniso found a job in insurances. He is now deceased.

Francis Don Mokhesi, Joyce’s brother, died of a heart attack in 2001. He has never been able again to play soccer professionally.

Duma Khumalo

Duma Khumalo kept fighting for acknowledgment of their innocence. In 1996 he testified for the TRC about the role of the legal system in the days of Apartheid. Later he worked for the Khulumani Support Group giving counseling to the victims of Apartheid. He co-authored the play He left quietly, based on his own life. He also played a part in it. His sudden death in 2006 at the age of 48 came as a shock. ‘It is impossible to come away from any single conversation with Duma Khumalo without having learned something new about yourself or the world61.’

The Upington 14

Of the Upington 14 on death row half of them are no longer alive 62. Gideon Madlongolwane, Evelina de Bruin’s husband, died in 1996. Evelina de Bruin (79) died in 201263. Albert Tywilli died in 2019 at the age of 61. The other deceased are Andrew Lekhanyane, Wellington Mazisa and Xolile Yona. Their dates of death are unknown.

Tros Gobula lives and works in Namibia. David Lekhanyane is an employee at the district municipality ZF Mgcawu. Zonga Mokgatle, Zuko Xabendlini and Booi Japhta are employed at the Dawid Kruiper Municipality. Kenneth Khumalo works for the Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs in Upington. Justice Bekebeke is Director-General of the Northern Cape Province.

Twelve of the Upington 26 were not sentenced to death. Of them Ronnie Mazisa, Abel Kutu, Jeffrey Sekeya, Xoliswa Dube, Roy Swartbooi and Ivan Kaza are deceased.

Enoch Nompandwana lives in Johannesburg, Elijah Matshoba works in a hospital in Upington, Sarel Jacobs is employed at the Dawid Kruiper Municipality, Fena Bostaander is employed at the district municipality ZF Mgcawu, Neville Witbooi was a municipal councillor and Barry Bekebeke is working at a youth detention centre.

The price of victory

The Upington 14 and the Sharpeville Six were finally released after an excruciating period of life between hope and fear. Would they die or live, would they be free or captive?

For a long time Western leaders have, against better judgment, defended the legal system of the colonial Apartheid regime. They were intentionally unwilling to acknowledge the mounting evidence of the innocence of the Six and the 14. Economic interests prevailed over justice and people. Ultimately they gave in because of a resolute national and international campaign. The Sharpeville Six and the Upington 14 were saved but not done justice. This trauma would last the rest of their lives. Those responsible for this injustice and their accomplices went and go unpunished.

Joyce Mokhesi

Joyce Mokhesi wrote: ‘Each has learnt that life will not be predicted, that no struggle is too hopeless, that victory always carries a price, and that years after the cries of the battle are heard, that price will go on being paid. And each of us is paying, each is living in a country past caring for its victims, each has adjusted to what will no longer be done, to capabilities lost, to opportunities that did not arise. (..)And each tries for a while to jump aboard the new South Africa, and each fails. We are too tired to have a vision of the future. We struggled and suffered for those who come after us, and we can only hope that they will look behind and acknowledge their inheritance with an understanding that we, for our part, did not always show to those who needed it64.’

______________________________________________

© Marjan Boelsma, 24 mei 2020.

With thanks to Rita Grijzen and André Kaïjim

Translation into English: HippoLingo

©Pictures: Azania Komitee, Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms. Reproduction of articles or parts of articles is authorized, provided the source is acknowledged and that passages and quotations are not placed in a different context

Footnotes

[1] ‘The legal doctrine of ‘common purpose’ in South African criminal law considers all parties liable who have been in implicit or explicit agreement to commit an unlawful act, and associated with each other for that purpose, even if the consequential act has been carried out by one of them. It relieves the prosecution of proving the causal link between the conduct of an individual member of a group acting in common purpose, and the ultimate consequence caused by the action of the group as a whole.’ https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/51032/Kistner_Common_2015.pdf?sequence=1

[2] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/

[3] The Sharpeville Six Committee was formed in 1986 by the Azania Komitee and Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms. The committee worked closely together with Joyce Mokhesi, sister of Francis Mokhesi, one of the Six

[4] ‘Townships, which are areas that were reserved to accommodate ‘Non-Europeans’, were formally established from the beginning of the 20th century and were for people who did not belong to the racial classification of ‘whites/Europeans’. Initially, the purpose was to control Black people, who were mainly workers. Planning was based on the management and control of “natives” and was strongly influenced by racist policies and the notion of what constituted a ‘Non-European’ lifestyle. Luvuyo Mthimkhulu Dondolo: https://uncensoredopinion.co.za/covid-19-spatial-plan-and-human-settlement-enterprise-in-south-africa/

[5] Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[6] The PAC was banned in 1960 https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/

[7] The organizations of the Black Consciousness Movement were banned in 1977 https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2019/08/25/soweto-uprising-1976-one-sided-international-solidarity/

[8] Joyce Mokhesi wrote that in 1986 the ANC (African National Congress) affiliated UDF decided to use the rent strikes for its national strategy. ‘The young brought to the ANC their ideas many derived from the BCM the previous decade. As a result the dominance which the ANC came to enjoy by the late 1980s was one more of emotional affiliation and acclamation than ideology and organisation. Many of the organisations’ members at the grassroots might be heard to express Africanist opinions and Africanist criticisms of the party’s leadership.’ [1][1] Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[9] AZAPO was formed in 1978 https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2019/08/25/soweto-uprising-1976-one-sided-international-solidarity/

[10] ibid

[11] Nyakane Tsolo led the anti-pass laws campaign in Sharpeville in 1960 https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2018/05/08/sharpeville-2/

[12] Tom Lodge SHARPEVILLE AND MEMORY, University of Limerick https://www.gold.ac.uk/media/documents-by-section/departments/history/Lodge_Sharpeville-and-Memory_Nov2011.pdf

[13] Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[14] ibid

[15] ibid

[16] ibid

[17] ibid

[18] Tom Lodge SHARPEVILLE AND MEMORY, University of Limerick https://www.gold.ac.uk/media/documents-by-section/departments/history/Lodge_Sharpeville-and-Memory_Nov2011.pdf

[19] In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, New York University Press, 1998

[20] ibid

[21] Ibid

[22] Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[23] ‘There are 134 recorded political executions of freedom fighters at the gallows in Pretoria Central Prison between 1960 and 1990. Ninety-four (94) plus one of them are members of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) of Azania, having participated in the Poqo Insurrection of 1961 to 1967, and the one Azanian National Youth Unity militant who was executed in 1987. The others belonged to various formations of the broad liberation movement’ http://mayihlomenews.co.za/the-forgotten-seed-of-a-new-nation/#more-3853 According to Madeleine Fullard, head of the MPTT (Missing Persons Task Team) 0f the TRC is: ‘The majority of the prisoners hanged during the period 1960 to 1990 were from the PAC.’ John Harris was the first and only white person to be hanged for an act of resistance against the Apartheid regime (1965) https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv02167/04lv02264/05lv02335/06lv02357/07lv02372/08lv02375.htm

[24] https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2019/08/25/soweto-uprising-1976-one-sided-international-solidarity/

[25] Details on the legal system are based on the book In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, New York University Press, 1998

[26] Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[27] ibid

[28] ibid

[30] Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[31] One year after the Six had been saved ‘when death penalty was still enjoying a brief period of political importance, a leading member of the South African Council of Churches paid some visits on death row. His words of comfort and understanding were restricted to those considered ‘political prisoners’ or ‘patriots’, a coded phrase denoting those who had been ‘adopted’ by the UDF. The others deemed criminals, were not adopted or visited’. Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[32] Joyce Mokhesi: ‘These are my war wounds, these are the records of how I was made. My body my life. They had me suffer for my victory, but I won, I refused to confess, refused to tell lies against myself, refused to help harm others.’ Till the death sentences were pronounced she had believed justice would be done. Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[33] Joyce Mokhesi studied at the university of Witwatersrand in South Africa, the Ruskin College and in Oxford, Engeland and at the La Trobe University in Australia. For a while she was acting Secretary-General of the Commercial Catering and Allied Workers Union of South Africa

[34] PAC (Pan Africanist Congress), ANC (African National Congress), AZAPO (Azanian People’s Organization), BCMA (Black Consciousness Movement of Azania), UDF (United Democratic Front), NF (National Forum)

[35]Activities in the Netherlands in 1979/1980 and 1990. Soweto, Black Consciousness, Biko https://tegenhetvergeten.nl/en/2019/12/15/activities-in-the-netherlands-in-the-70s-80s-and-90s-soweto-black-consciousness-biko/

[36] Azania Vrij, 1986, 12-2

[37] The petition was supported by Amnesty International, PPR MPs(Political Party of Radicals), PPR board, PvdA MPs (Labour Party), FNV (Federation of Dutch Trade Unions), Kerk en Vrede (Church and Peace), NIO (New International Development Policy), Stichting tot Steun aan Demokratische Krachten (Foundation in Support of Democratic Forces), X-Y Movement, Mission and World Diaconate Reformed Churches, Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms, APA (Portuguese Association Amsterdam), DIDF (Turkish Democratic Workers’ Association), the Eritrean Workers’and Students’ Union and Rotterdam Against Apartheid

[38] That would later increase to 4500 signatures

[39] Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[40] ibid

[41] ibid

[42]McBride (ANC) was sentenced to death for a bomb attack in Durban. He too got a stay of execution and was eventually released

[43]Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[44] ibid

[45] ibid

[46] ibid

[47] ibid

[48] No.10 record of conversation (MT, Joyce Mokhesi) [‘Sharpeville Six’ case] [declassified Dec 2017]: https://c3f0094bc71154bde99f-7d29b9e6510ace11918affa010656132.ssl.cf2.rackcdn.com/880712%20no.10%20cnv%20PREM19-2526%20f225.pdf

[49] ibid

[50] Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[51] European Commission press release https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_88_493

[52] Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[53] The Treason-trial was a trial in Johannesburg. During a raid 156 people, among them Nelson Mandela, were arrested and in 1956 they were charged with treason. The main proceedings in court continued till 1961, when all defendants were found not guilty https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1956_Treason_Trial

[54]Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998

[55] https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2011-12-15-prison-was-a-death-factory/

[56] Lubowski was a member of the Namibian liberation movement SWAPO (South West Africa People’s Organization)

[57] De Klerk had succeeded Botha as President of South Africa in 1989

[58] Sharpeville Six Committee, Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms, D’66 Rotterdam (Democrats 66), FNV, GroenLinks Rotterdam, NIO, Rotterdam Against Apartheid, Sihambile Cultural Group, STAR (STAR was an organization of migrants and non-immigrant Dutch which fought against Apartheid, racism, discrimination and colonialism. Stemming from the former Black People in Holland Against Apartheid. Azania Vrij, 1988,nr 4), Stichting tot Steun aan Demokratische Krachten, VVD Rotterdam (People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) and X-Y Movement

[59] In 1980 the Black Municipal Workers Union (BMWU) was formed. In 1981 the name changed to South African Black Municipality and Allied Workers Union (SABMAWU). In 1989 after a number of other unions came together and the name changed to Federation of Municipality and Allied Workers Unions (FEDMAWU). Info Phillip Dhlamini, trade union leader and founder of BMWU.

[60] The Sharpeville Six, The South African Trial that shocked the world, 1990 by Prakash Diar, McClelland & Stewart Inc. The Canadian Publishers, Toronto

[61] https://khulumani.net/in-the-news/sharpeville-six-member-dies/2006/02/14/

[62] https://www.groundup.org.za/article/former-upington-26-death-row-prisoner-remembered/

[64]Peter Parker and Joyce Mokhesi, In the Shadow of Sharpeville, Apartheid and Criminal Justice, New York University Press, 1998